HISTORY OF ALASKA TOURISM, PART 3 A Steady ‘Boom’ In Tourism Post World War II December 29, 2010

But the war also did two things to ensure that Alaska’s tourism future would be very bright indeed. First, more than 100,000 US and Canadian service members were stationed in Alaska. Large numbers of veterans and their families would return to Alaska in the next generation bringing thousands of visitors to Alaska who wanted to experience Alaska in a more peaceful way.

First truck to go over the rough cordurouy road along the Alcan Highway (Now known as the Alaska Highway) route was an Army jeep. CREATED/PUBLISHED - 1942. United States. Office of War Information. Overseas Picture Division. Washington Division; 1944. PART OF Farm Security Administration - Office of War Information Photograph Collection (Library of Congress)

And the construction of the Alaska Highway during the War was a boon for the state just as Americans began to really experience the freedom of “personal” travel in their automobiles. There had been talk about a highway to Alaska since the early 1920s. In 1928, Donald McDonald of Fairbanks formally proposed the United States and Canadian governments work together on a road. McDonald’s plan was to connect a road from Hazelton British Columbia to Fairbanks. He called it the International Pacific Highway.

Dumping mud into the side of the highway and widening the road, along the Alcan Highway. CREATED/PUBLISHED 1942. United States. Office of War Information. Overseas Picture Division. Washington Division; 1944 -- PART OF Farm Security Administration - Office of War Information Photograph Collection (Library of Congress)

But with the coming of War in the Pacific, Alaska became a critical part of the North American Defense Grid, especially after the Japanese attacked and occupied two islands in the Alaskan Aleutian chain in June of 1942. The attacks on the Aleutians were generally a diversionary tactic by the Japanese, but many in Alaska expected the Japanese to continue to march across Alaska and it became of great military importance to improve the defensive supply chain to the state. Initially military supplies and troops were ferried to the state up the old steamship routes on the inside passage and several of the shipping lines had most of their vessels requisitioned to the war effort. But with the fear of Japanese submarine attacks increasing two other transportation corridors were planned. First, the Army Corps of Engineers began expanding old and building new airports in the Territory. The airfield on Annette Island – which would serve as Ketchikan’s primary airport for three decades – was completed in 1942. The airfield had been in the “construction” stage for nearly a decade, starting in the early 1930s, but the outbreak of war pushed it to completion. Along with airports in Yakutat, Kodiak and Anchorage it became an important cog in the war effort.

Annette Island Airport - circa 1957

After the war, both the United States and Canadian governments poured money into improving the highway, eventually turning it into a significant access point for the north. By the 1990s, several hundred thousand visitors were arriving in Alaska via the ALCAN each year. In general, between 1946 and 1990, the tourism industry steadily increased in Alaska. But in some ways, Southeast Alaska didn’t see the rapid increases that the rest of the state did, at least until the early 1960s. The primary reason was that the steamship lines – that had provided nearly all the visitors to Southeast prior to the war – were running at reduced schedules, generally because they had not gotten the use of all their vessels back from the military. There were also fewer American willing or able to take long ocean voyages, at least until the 1950s. But that didn’t keep the locals from at least trying to attract visitors to see the local scenic wonders, and buy a few curios while they were at it. By 1940, in Ketchikan, the Forest Service was trying to drum up interest in Ketchikan. It released a pamphlet called “Foot Trails and Drives Near Ketchikan.” Among the highlights was the Deer Mountain trail, which it termed “moderate” on the climbing scale, although it did warn hikers to stay to the trail and not try to “cut off” the “switchbacks.” It noted that climbers were frequently getting lost on the mountain when they left the trail. Other local highlights were “Tongass Park” and “Rotary Beach” and also a new attraction – a “primitive Indian village” under construction at Mile 10 North Tongass the Forest Service was calling “Totem Bight.” Salmon remained a popular draw, particularly in Ketchikan, where a large salmon stream was only a couple of blocks from the ship docks and locals had built a fish ladder in 1936 to make view of salmon going the up falls even easier. There was also a boardwalk along the lower reaches of Ketchikan Creek, but since it was also the town’s infamous Red Light district visitors were “discouraged” from using it to view the salmon pooling below the falls. Quite a few did, however.

New England Fish Company complex from the Tongass Narrows, circa 1930

Taxi cabs were also available to provide guided “tours” of the plants and then stopped at Mission Street so the visitors could get their picture taken in front of Ketchikan’s Welcome Arch. Visitors to Ketchikan also visited the Territorial Hatchery beginning in the 1950s and also occasionally toured Ketchikan’s cold storage plants as well.

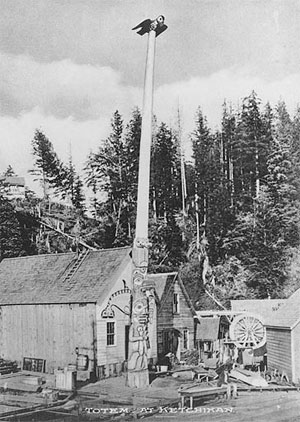

Another drawing point for Ketchikan was the totem poles for which the community would soon become famous. The Chief Johnson pole was erected in 1901, according to Frank Norris in his “Gawking at the Midnight Sun” history of Alaskan tourism. “By 1905 it was followed by a totem honoring Captain John Swanson, an early trader,” Norris wrote. “Numerous totems were admired there in 1913, but by 1921, only two were seen by most tourists. They were the Johnson totem and the Kyan totem. In the mid 1920s, tourists also found totems while visiting the town’s Indian graveyard.” Norris noted that in the 1920s, residents began to appreciate the value of the Native totems and made efforts to display them. “In 1929, the Ketchikan City Park received six poles from abandoned Tongass village,” Norris wrote. “In the late 1930s, the US Forest Service moved 22 poles from Cat and Village islands to the Saxman Totem Park, three miles south of town. Finally, the Civilian Conservation Corps built a new Haida community house, entrance pole and column at Mud Bight, ten miles north of Ketchikan in 1938. It had been intended to be the start of a model town, but World War II stopped work. Not until the 1970s were the majority of today’s poles erected at the site.” Early visitors were also interested in seeing some of the original villages. Early steamships stopped at both Tongass and Howkan (on Long Island west of Prince of Wales) villages. The abandoned village of Old Kasaan on Prince of Wales was also a popular site for early visits. But although Alaska now had a direct – albeit long – link with the Lower 48 via the ALCAN, wartime travel restrictions pretty much wiped out the visitor industry. Hundreds of thousands of people –soldiers – were visiting Alaska, but not by choice. In 1945, the territorial legislature created the Alaska Development Board. “The tourism industry will be bigger than the $50 million salmon industry,” Gov. Ernest Gruening noted at the time. “Our job is to prepare for tourists and not turn them away.”

Totem Park, Saxman

The same message was taken to Washington DC in September of 1945 by a delegation of Alaskan officials led by Captain A.E. Lathrop of Fairbanks., the publisher of the Fairbanks News Miner. “Alaska is a land of wonderful opportunities but they are not to be won on a shoestring,” Lathrop’s executive secretary Miriam Dickey told the Associated Press on Sept. 26, 1945. “We have scads of letters from people who want to visit Alaska. Tourist facility development is Alaska’s first need.” In the late 1940s, there were a handful of American and Canadian shipping lines providing passenger and tourist service to Southeast Alaska. The most prominent of these lines was the Alaska Steamship Company which had been operating in Alaska in 1894. By the 1930s, it was the largest line to serve Alaska. But it struggled to regain its footing after the war when 15 of its vessels had been requisitioned into the navy and merchant marine. Prior to the war it had also received generous subsidies from the US government to provide service to the outlying communities in Alaska. But those began to dry up after the war. Rising fuel and labor costs also played a part, as did increasing competition from the airlines that were using the new airports built as part of the war efforts. But, still Alaska Steamship held on. One of its more interesting “promotions” in the post war years was a pamphlet advertising Southeast Alaska and the Inside Passage as the “Lover’s Lane of the Seven Seas.” It was short on “details” but it did extol the beauty of the passage through the endless forests and islands and the quaint native villages and bustling frontier communities. The steamships, in those days, had space for approximately 200 passengers along with the cargo in “top class” accommodations. Looking at the passenger lists, from those days, though, it is clear that the vast majority of the passenger traffic was locals coming and going from Alaska rather than tourists. By 1949, Alaska Steamship was losing boatloads on money on its passenger service. In a full page advertisement in the Alaska Sportsman, company president F. A. Zeussler bemoaned the economic climate but assured locals that the Alaskan Steam was committed to retaining passenger service to Alaska if it received appropriate “cooperation” from the Federal Government. Apparently, it did not, because in 1954, it suspended passenger service temporarily. It would never be resumed for the decade and a half that Alaska Steam remained in service. Although other smaller US lines, and the Canadian Pacific and Canadian National lines, continued to provide passenger and visitor service to Alaska, this left Southeast Alaska in particularly cut off from its traditional mode of access to Seattle and points south. Air travel was increasing – with both Pan American and Pacific Northern – through Annette, but it was still a fairly expensive way to come and go.

January 21, 1954 First DC-6B Stops at Annette

From 1963 on, although most freight was still being barged into the region, passenger vessel service was entirely provided by the “Blue Canoes” which provided a connection to both Prince Rupert and the Seattle area. In the early 1950s, in the last years of the Territorial Government, Alaska began to take tourism marketing a little more seriously. The Alaska Visitors Association was created in 1950. At the heart of the AVA’s mission was to publicize Alaska. At the time, efforts to promote the Last Frontier and to spur the visitor industry were limited to pamphlets put out either by the Territorial Government or by individual businesses such the Copper River And Northwestern Railroad near Cordova or Pruell’s Jewelry in Ketchikan. The Steamship lines also advertised heavily. There were also attempts to develop promotional magazines throughout Alaska but almost all were very short lived. In 1935, a relatively permanent tourist-oriented magazine did start up and it continues to this day. The Alaska Sportsman began in Ketchikan as a hunting and fishing magazine but was quickly publishing articles geared toward tourists and other people interested in the Alaskan lifestyle. The magazine’s name was changed to Alaska Magazine and it remains the dominant Alaskan publication. Toward the end of World War II, the territorial government created the Alaska Development Board, an off-shoot of an earlier group called the Alaska Planning Council. “The development board sought to promote tourism by providing assistance to potential investors, by locating sites for tourist development, by assistance to existing resorts and by issuing publications detailing the tourist opportunities,” Norris wrote. As the more utilitarian steamship companies began to leave the market in the late 1940s and the 1950s, a new type of ocean going vessel took their place. It was less concerned with transporting people from town to town than it was with “transporting” them from away from their “humdrum” daily lives into the “adventure of a lifetime.” Compared to today, they were smaller and rudimentary in amenities, but they were clearly “cruise ships” and not coastal steamers. One of the first “lines” to emerge was Alaska Cruising Inc in the late 1950s. Its one and two week excursions were on the “pocket” cruise ships, the SS Glacier Queen and the SS Yukon Star, both converted steamers that could hold up to 250 passengers each. The trips ranged from 7 to 10 days and cost between $225 and $355. They only operated from May to September and also coordinated with “shore excursions” in the communities they visited. Other small lines also joined the fray. But, in the 1960s, the Alaska cruise industry was still tiny. In 1964, for example, only 11,000 visitors came north into Southeast Alaska, compared to 11,650 ferry passengers and 13,250 airline passengers. By 1970, the cruise line numbers had tripled to more than 30,000. And bigger growth was yet to come.

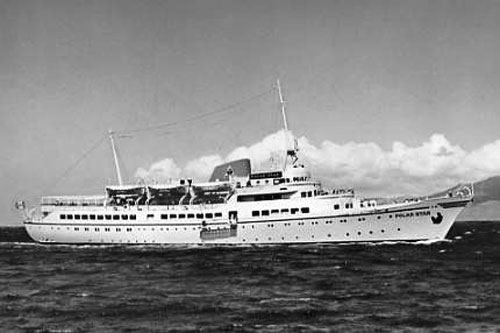

Polar Star

At the time, Westours was the largest tour operator in Alaska, but ships like the Polar Star were soon outstripped by larger competitors. One of the first was the P&O Lines “Arcadia” which first started visiting Southeast Alaska in June of 1970. The Arcadia was more than 700 feet long and carried more than 1,800 passengers and crew. It was way too big to fit at the old wooden docks in Downtown Ketchikan. The sight of the 11-story tall leviathan anchored in the harbor worried local businessmen that the community would soon be bypass by ships too big visit Ketchikan, according to former Ketchikan Historian Mike Dunning in his article “Tourism in Ketchikan and Southeast Alaska” in the Fall, 2000 issue of “Alaska History,” the publication of the Alaska Historical Society. “Pete Gilmore, whose Seattle-based company Skinner Corporation owned the old Alaska Steamship Company Dock in Ketchikan, derided the city for… allowing its dock facility to languish,” Dunning wrote. “The vast majority of tourists who visited Ketchikan already did so by cruise ship, Gilmore pointed out, but now he claimed that Ketchikan was failing to take full advantage of the lucrative tourist trade.” Gilmore noted that Ketchikan was one of the few cities in the world where cruise passengers could disembark right in the heart of town. “Ketchikan offers little to the tourist once he gets here … a few wooden streets, some drunks stumbling out of bars, that’s it,” Gilmore told the Ketchikan Daily News on Aug. 29. 1972. “Cruise ship passengers are wealthy experienced travelers. They are used to seeing a couple of Indians dance. The city should offer something different, something unique. Ketchikan has to remember that it’s competing with tourist traps.” Dunning also noted that representatives from Ketchikan, including Cliff Taro of Southeast Stevedoring and Southeast marine pilot Capt. Casey Moran were discovering that “tour professionals” were concerned that Ketchikan had too little to offer visitors. “In fact (many of) the original tour proposals excluded Ketchikan in favor of Sitka, Glacier Bay, Juneau, Haines and Skagway,” Dunning wrote. “It took some time and extensive salesmanship by Taro ‘before we were able to convince the major cruise lines that Ketchikan had something indeed to offer their customers, the tourists.’ “ It also helped that in 1971, Chuck West sold “Westours” to Holland America, which brought that line into the Southeast Alaska market. Other bigger boats that began coming to Alaska in those years included the Sitmar Cruises Fairsea, the Spirit of London and the first of the Holland American boats, the Prinsendam in 1973. The Spirit of London was originally owned by P&O but when P&O bought Princess Cruises, its name was changed to the Island Princess. Princess Cruises – soon to become one of the most famous lines in the world – got its name from the fact that the Canadian Pacific steamship line had loaned the Princess Patricia to a Los Angeles based entrepreneur for some short Mexican cruises in 1966. In 1972, Chuck West sold Westours to Holland America. Soon, Pacific and Orient Lines, the forerunners of the Princess Cruises of Loveboat renown entered the market with the first “modern” larger ships. In 1973, eight different ships made 103 stops in Ketchikan. Bill Cribben, manager of the Ketchikan Chamber of Commerce told the Ketchikan Daily News in 1973, that tourism was about to overtake the fishing industry as Ketchikan’s “second industry.” At that same time, Frank Seymour, the executive director of the Ketchikan Visitors Bureau, also told the Daily News that he expected the tourism industry to double in size in the next decade. Len Laurance, a local tourism entrepreneur estimated in the early 1970s, that more than a million cruise visitors would eventually come to Alaska each summer. In 1975, the Alaska Visitors Association formed in first marketing council and by 1977 total visitor numbers to Alaska topped 500,000. Just 60,000 of those visited on cruise ships. Those were the first “boom” years for cruise passengers, driven in no small part by publicity over the “Love Boat” television series which featured Princess Cruise Line ships. Most of the “Love Boat” episodes which aired from 1977 to 1986, featured sunnier locals, but occasionally there were “special” episodes set on the Alaska run, including one in Ketchikan that featured a dogsled “race” run on wheels. By 1982, the number of cruise passengers to Alaska had increased to 82,000 and from there on growth was fairly steady into the early 1990s when 421 ship visits brought 380,000 visitors in 1994. That number of visitors had doubled by 2002, as the cruise lines began replacing older ships with newer, larger ones. The average sized cruise ship was now carrying more than 2,000 passengers each visit. Rapid growth continued on until the number of cruise passengers to Ketchikan topped 900,000 in 2008. Juneau – the biggest port in Southeast – drew more than 1 million visitors that year. It was also during this time that tourism and the “summer visitors” truly became big business throughout much of Alaska and politically controversial. As communities – primarily in Southeast Alaska and the Railbelt – rushed to remake their economies to take advantage of the influx – there was also concern about rapid growth in the industry what effects it was having on those communities and the state in general. Some cities – like Ketchikan and Juneau – instituted “head taxes” in order to help pay for some of the perceived costs of the booming industry. A large statewide tax was also approved in 2006 that levied a nearly $50 tax on all cruise passengers that also provided funding for environmental safeguards and regional infrastructure projects. In response to that tax, cruise lines cut back on their Alaskan operations. When combined with a significant nationwide recession, 2009 showed the first decline in visitor numbers in over a decade. The Cruise industry also filed suit against the state over the size and the implementation of the “head tax.” In 2010, the state Legislature lowered the amount of the tax and the cruise industry dropped its lawsuit. As of 2010, cruise ship passenger numbers appeared to be increasing again, but had not yet reached the pre-2009 numbers. Tourism in Alaska was growing, once again, but no one was making any predictions about the future of the industry. Except, of course, Alaska’s first tourist, William Henry Seward, who had given a speech in Sitka in 1869. “No man can exaggerate the treasures of the territory,” he concluded.

Related Articles:

On the Web:

Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us

Publish A Letter in SitNews Read Letters/Opinions

|

|||