History of Alaska Tourism, Part 2 Tourism Grew Significantly From Goldrush To World War II Alaska Benefited Twice From Uncertainty In Europe By DAVE KIFFER August 16, 2010

In May of 1899, the steamer George W. Elder left Seattle carrying what was called the "Harriman Expedition."  Creator Edward S. Curtis, 1868-1952 Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

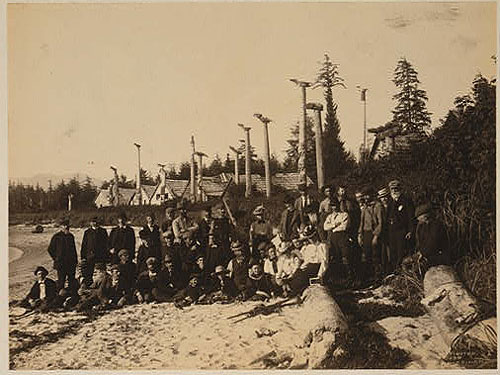

Between May 31 and July 30 the expedition made numerous stopped throughout Alaska and Siberia, including Metlakatla, Ketchikan and the abandoned village at Cape Fox. The voyage generated significant media coverage and when it was over the scientists, photographers, artists and writers on board collaborated on a 14-volume collection of writings about the trip that was published over the next decade. "For years (it) was revered as the standard reference work on Alaska," Frank Norris wrote in his 1985 history of Alaskan tourism "Gawking at the Midnight Sun." "It was repeatedly consulted by scientists, developers and potential tourists." Although the Harriman voyage did significantly add to the scientific knowledge of Alaska, it was not without controversy. Scientists and other members of the expedition had no qualms about taking items from abandoned villages either as souvenirs or for ethnographic research. Later generations would consider these actions theft or looting. In 2001, a group of scientists retraced the steps of the Harriman Expedition and several items were returned to the descendants of the Cape Fox villagers. ![jpg The expedition vessel, George W. Elder, at dock (thought to be in Sitka, Alaska) and two small boats loaded with fish in the foreground, 1899]](expedition.jpg) Creator Edward S. Curtis, 1868-1952 Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

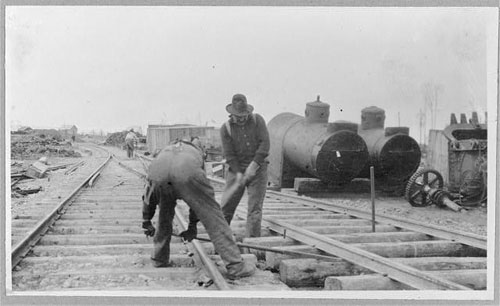

Ketchikan was particularly well situated, especially after 1900 when the Alaskan entry customs station was moved from Mary Island to Ketchikan and all ships entering the district were required to stop there. Prior to 1900, most of the steamships that came to Alaska were owned by Pacific Coast Steamship Company but in the first decade of the new century, three other lines - Alaska Steamship Company, the Canadian Pacific Railroad Company and the Humboldt Steamship Company were also plying the inside waters. The Pacific Coast Steamship Company was billing its run as the "totem pole route." Its primary stops were in Wrangell, Juneau, Treadwell and Sitka, but also frequented Douglas, Metlakatla, Ketchikan and Haines. Occasionally the steamers also stopped at the abandoned villages of Old Kasaan and Fort Tongass. Even then, the steamship lines were also experimenting with what is now called "niche" tourism. In his book, Norris noted that PSCS was offering "Native basket" tours that allowed visitors to spend more time in the Native villages. In some cases, the more adventurous visitors even travelled between locations in Native canoes. Visitors were also becoming interested in Native dance as well. As early as the late 1880s, a Juneau entrepreneur named Martini began scheduling native dance "performances" for the visitors, charging $1 per show, according to information from the Alaska State Museum. By 1900, such shows were part of the visit to several communities on the steamship run. Post cards showing Natives, totem poles, and other indigenous items were also very popular with the visitors. The first "curio" shops began appearing in Southeast Alaska well before the turn of the century as local merchants realized the value of "trinkets" and other items to the visitors. Clark and Martin's trading post in Ketchikan was providing Native handicrafts as early as 1890. And display ads in the Ketchikan Mining Journal from 1900 advertised "curios" in several Downtown stores, most notably Tongass Trading which continues to stock "curios" to this day. Photography was popular in the early days as well, with the Hunt Family selling local photos and post cards out of their Front Street store in Ketchikan as early as 1902. One of the earliest "jewelry" stores in the district was Kirmse's in Skagway which opened at the height of the Gold Rush in 1898. By 1911, it had expanded into the first jewelry store in Ketchikan to meet the shifting steamship trade which was then focusing on communities other than Skagway. By 1913, Gus Pruell had purchased the Kirmse store and would operate it as a curio/jewelry store until he died in the mid 1950s. Tom Sawyer bought the store and it still operates 2010. Glacier tours also remained popular even though Glacier Bay was still off limits and visitors "contented" themselves with the Taku Glacier south of Juneau and the Davidson Glacier a non-tidewater glacier near Haines. Visitors were also interested in wildlife tourism in this period and it was not unusual for guides to arrange fishing and wildlife viewing opportunities. Most excursion boats carried along fishing poles and passengers were allowed to drop lines off the stern. After the turn of the century, tourism began to grow in other areas of state as visitors began to follow the trails blazed by the gold seekers who sought riches inland. In 1898, a 400 mile pack trail had been built from Valdez into the gold fields around Eagle. Eventually that "trail" was turned into a wagon road that eventually became the Richardson Highway in the 1920s. Railroads like the White Pass and Yukon in Skagway and the Copper River and Northwestern Railway in Cordova also helped to open up the "Interior" to the visitor trade. Further Interior gold strikes in such places as Fairbanks and 40 Mile also boosted traffic along the Yukon River, increasing access and opportunities for tourism. When the Bering Sea weather permitted steamships also began visiting the newly minted boom town of Nome. One of the most spectacular "excursions" of the time was the "Belt Line" excursion. It involved steamships to Skagway, the White Pass and Yukon on to Whitehorse, and paddlewheelers on to Dawson, Fairbanks, across the Arctic Circle into the "Land of the Midnight Sun" and eventually St. Michael and Nome. The "Belt Line" excursion as it was called by Pacific Coast Steamships took anywhere from 21 to 30 days and was marketed for between $250 and $300 a person. The construction of the Alaska Railroad from Seward to Fairbanks from 1914 to 1923 also opened up the Interior to visitors in a significant way. Most notably, its route north of Anchorage near Mount McKinley made Alaska's most significant natural "wonder" accessible to casual visitors for the first time, although initially most of the traffic on the line was commercial.  Between ca. 1900 and 1916 Forms part of: Frank and Frances Carpenter collection (Library of Congress). Gift; Mrs. W. Chapin Huntington Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. Mt. McKinley National Park was established in 1917, albeit in a much smaller size than the current Denali National Park. It was initially a fairly small wilderness refuge and didn't even include the summit of the mountain in its original boundaries. By 1923, there were organized tours into the park (by horse and wagon) a tent camp had been set up at Savage River, 12 miles inside the boundary. Tented cabins were available for $7.50 a night, according to "The Lure of Alaska" a 2007 publication of the Alaska State Museum. The second preserve in Alaska would be the Glacier Bay National Monument in 1925. But in general, most tourism to Alaska remained confined to Southeast Alaska and Inside Passage prior to World War I. Even in the communities that had steamship visitors, the economic impact was slight. "It (tourism) was controlled by steamship companies which had headquarters outside Alaska, and the amount of time the tourist spent off shop provided almost no opportunity for local economic development based on tourism," Norris wrote in 1985. "The shipboard experience, and the tendency to segregate tourists onto excursion steamers, also gave tourists few opportunities to interact with local residents. Alaskan development boosters, such as local chambers of commerce and government officials, reciprocated by almost totally ignoring the existence of the industry."  Photo by Johnson. Forms part of: Frank and Frances Carpenter collection (Library of Congress). Gift; Mrs. W. Chapin Huntington; 1951. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

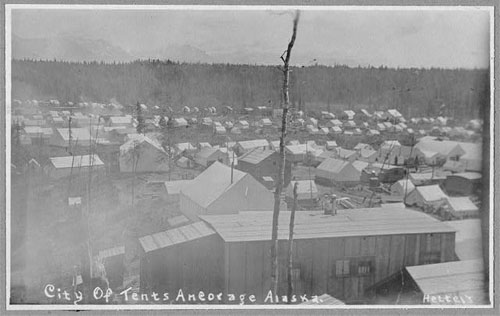

"(1915) was deemed the greatest year by far in Alaska's history for tourists," Norris wrote. "And many in the Territory began to notice tourism for the first time. The industry declined somewhat (when the US entered the war in 1917) but zoomed up again afterwards. Word of mouth recommendations as well as commercial advertising helped people choose an Alaskan vacation." Norris also noted that steamship services to the region were also changing, as business travelers and area residents were making up a larger portion of the passengers and excursions voyages were decreasing. The Pacific Coast Steamship Company, which had dominated the trade since the 1880s, went out of business in 1916 and was eventually superseded by the Pacific Alaska Navigation Company, which was known colloquially as the "Admiral Line" because it ships had "Admiral names. It soon changed its company name to the Pacific Steamship Company. Meanwhile, according to Norris, the Humboldt Steamship Company and the Northland Steamship Company continued to serve the coastal communities "but neither carried many tourists." Beginning in 1901 and expanding rapidly in the 1910s, the Canadian Pacific Railroad steamers soon began to carry a larger portion of the Alaska visitor trade. Soon ships like the Princess Royal, Princess Charlotte, Princess May and the Princess Sophia became familiar presences on the Inside Passage and in the media throughout western North America as the railroad embarked on a significant advertising campaign. The Princess ship were considered some of the most luxurious steamers of their time. Also in the 1910s, the first excursions began to explore the Southcentral Alaskan Coast, primarily Prince William Sound. In 1915, the small tent city of Anchorage then called Knik Anchorage - began to get some notice.  Date Created/Published: [between ca. 1900 and ca. 1930] Photo by Hettel. Forms part of: Frank and Frances Carpenter collection (Library of Congress). Gift; Mrs. W. Chapin Huntington; 1951. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

After 1921, the first significant

Alaskan motorcoach companies began to operate on the Richardson

and that boosted tourism into the Interior. A joint marketing/tour

agreement between the Alaska Railroad and the Alaska Steamship

Company further opened up the market. . A 1922, illustrated booklet,

ALASKA: The Richardson Highway-Valdez to Fairbanks, promoted

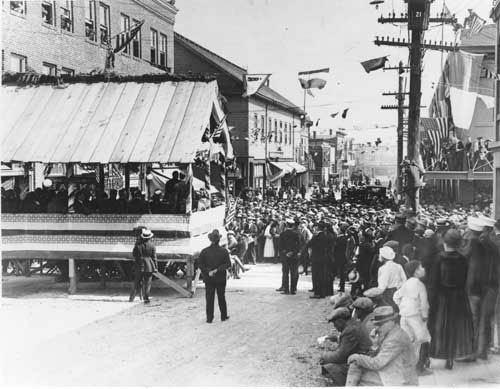

the route's history, scenic attractions and roadhouses. The government of Alaska also began to take the concerns of visitors a little more seriously late in the 1910s. Prior to then, questions from visitors were routinely handled by the staff of the Territorial Governor and few attempts were made to 'market' Alaska by the Federal government. But in 1917, the Bureau of Publicity was established. According to Norris, it was led by well-known journalist Elmer "Stroller" White and stayed in operation until 1921, also printing regional guides and disseminating information of "value" to visitors and to companies interested in Alaska. It also functioned as an employment service for those looking for work in the Territory. It was a short lived experiment, the legislature phased out the program in 1921 and the duty of "promoting" Alaska returned to the Governor's office until after World War II. The 1920s were good time for Alaskan tourism as the rest of the country enjoyed at economic boom. Federal estimates show between 20,000 and 30,000 visitors arriving in the middle to late years of the decade. A major event occurred in 1923 when President Warren G. Harding visited Alaska with an entourage of more than 80 people. The resulting newspaper attention, heightened when the President took ill and died in San Francisco at the end of his trip boosted tourism numbers to Alaska for the rest of the decade.  New York Times Photo, courtesy Tongass Historical Society

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Hollywood discovered Alaska and filmed several movies on location in the Territory. The most notable of the early movies was 1932's "Eskimo/Mala the Magnificent" by MGM which garnered plenty of publicity for the Territory and for Inupiat actor Ray Mala . The film won an academy award for film editing and had full scale premiers in California and New York City. Two prominent movies were filmed

in Ketchikan in the 1930s and helped boost the community's profile. But it wasn't just the movies that lured Hollywood. The fishing in Southeast Alaska became a major draw for movie stars and others. Many took advantage of a new type of tourism, high end boat excursions. The yachting trade was significant in Southeast Alaska from the mid 1920s through 1941 and the editions of the local newspapers not mention the national magazines such as Life devoted a fair amount space to the "rich and famous" at play in Alaska. Bing Crosby, Bob Hope, Fred Astaire and Gary Cooper were just some of the major stars who visited Alaska in the 1930s. Newsreels showed them and many of the captains of American industry enjoying the Alaskan outdoors. The timing was fortuitous because the 1930s were a period of a significant downtown for much of Alaskan tourism because of the Great Depression. The images of stars enjoying the territory built up a reservoir of interest that extended to the American middle class after World War II ended. But while the stars were enjoying Alaska in the 1930s most of the tourism industry was in a severe recession. Tourist numbers on the White Pass railway dropped 25 percent between 1929 and 1930 alone. Traveler numbers were off between 50 and 75 percent between 1929 aand 1933 iin most sectors, according to federal reports. The industry had begun to rebound somewhat by 1934, then in 1935 more national attention was brought to Alaska with the creation of the Matanuska agricultural colony north of Anchorage. Spreads in magazines national magazines helped remind residents of the Lower 48 of the allure of Alaska. Two other factors helped boost Alaska tourism in the later part of the 1930s. First, the uncertainty of the political situation in Europe turned many away from European trips just as similar concerns had in the 1910s. According to Norris, by 1936, there were more visitors interested in coming north than there were bunks on the available ships. Another factor in promoting Alaskan tourism was the rise of the air travel industry. Initially it was primarily the well-heeled who flew into Alaska often big game hunters and other sportsmen. But by 1936, Pan American Airways was already experimenting with flying boats between Seattle and Southeast Alaska and a variety of smaller carriers were providing point to point service within Alaska. Early "flightseeing" operations took advantage of visitor interest in places like Mt. McKinley and Glacier Bay. One area in which tourism was not making much of a mark in Alaska was automobile tourism. While it was possible to rent a car and drive on one Alaska's rare highways and wealthy visitors could arrange to have their vehicle shipped north for their Alaskan "adventures," there was still no practical way to "get" to Alaska in your car. Soon World War II would come

to Alaska, and change all that. (Next Tourism in Alaska, World War II to the Present)

On the Web:

Dave Kiffer is a freelance writer living in Ketchikan, Alaska. Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us

|