100 Years Ago Grand Trunk Railroad Came to Northwest BCBy DAVE KIFFER April 01, 2014

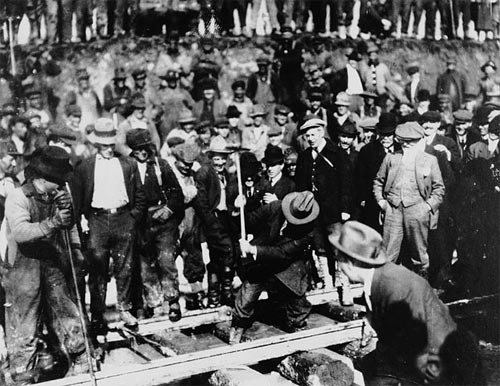

The Grand Trunk Pacific Railway’s last spike was driven on April 7, 1914 one mile east of Fort Fraser, approximately 100 miles west of what is now Prince George. Within days, the first trains were delivering passengers and supplies all along the new line from Alberta to Prince Rupert. It was heralded as a new era for the Northwest Coast, the dream of Charles Hays, the founder of the Grand Trunk Pacific and the town of Prince Rupert which he envisioned as the future “great port” of western North America. Among the celebrants at the last spike ceremony at Fort Fraser were Edson Chamberlain, the president of the Grand Trunk Pacific and Alfred Smithers, the chairman of the board of the directors. They had taken the train from Winnipeg and Montreal. A separate group, including Superintendent W.C.C. Mehan had come up the line from Prince Rupert. The Last Spike of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway, April 7, 1914, Fort Fraser

The eastern crew finished a few minutes ahead of the western crew and then the western crew put the last rail in place. Chamberlain drove the last spike, which was a standard black iron one, not a golden one. Then he gave gold watches to each of the crew bosses. The last track tie was painted “Point of Completion, April 7, 1914.” After the ceremony, the final 11-foot section was removed. It was later cut up and given away as paper weights. One of the sections resides in the Prince George Railway Museum. Charles Melville Hays was not on the hand for the completion ceremony because he had died two years earlier when the Titanic sank in the North Atlantic. Hays was returning from a trip to England to meet with investors for the railway, that he had started in 1903. The Grand Trunk Pacific Railway was a wholly owned subsidiary of the Grand Trunk Railway, one of the dominant lines in Eastern Canada and the northern Midwest of America. The Canadian Liberal government of Wilfred Laurier supported the Grand Trunk Pacific because of political disagreements it had with the Canadian Pacific Railway which had always been tied to the Conservative political establishment. Canadian Pacific had established a Canadian transcontinental line to Vancouver in 1885. The Laurier government also believed that a railway in northern British Columbia would cut transit time to Asia by a significant number of days. Hays used the support of the government to leverage 25 percent private investment in the Grand Trunk Pacific Originally surveyors had proposed terminating the new railway in Port Simpson, a trading village on the British Columbia coast adjacent to the Alaskan-Canadian border. But in 1903, the Canadians were shocked when Great Britain sided with America in a boundary commission that established the Alaska-Canada boundary. Canada had expected to receive salt water ports in what is now Southern Southeast Alaska south of the Stikine River, but the Commission narrowly chose to draw the boundaries as they are today. Canadian officials initially threatened to use force to enforce their view of the boundary, and US President Theodore Roosevely threatened to send a military force to Southern Southeast Alaska in response. According to the Derek Hayes’ 1999 “ Historical Atlas of British Columbia and the American Northwest,” the Canadians backed down from their threats and decided to establish a railway further south along the coast because it would be more “easily defensible” in the event of an American incursion. That decision allowed Hays to survey a line into Kaien Island and its spectacular deep water port, one of the largest ice free ports in North America, and begin planning for the creation of Prince Rupert. The railway construction began on September 11, 1905 at Fort William, Ontario. Work also began that same year in Alberta. The start of the eastern portion of the line spurred Hays to move forward on his terminus. On May 17, 1906, construction began on the community of Prince Rupert. By 1909, the community was sufficiently established to begin construction of the line east to meet the oncoming line which was by then completed through much of Alberta. Things were looking up for the railway and Northwest British Columbia. Hays lavishly predicted a port that would be larger than either Seattle or Vancouver and would have 50,000 residents. Then two disasters struck the under construction line. First in 1911, the Laurier government lost power after more than a decade in control. While the Liberal government had focused on development in Western Canada as a way of tying the country together, the incoming Conservative government of Robert Borden was much more concerned with Eastern Canada. While the new government did nothing to stop the construction of the Grand Trunk Pacific line, it began to question the federal government’s agreement to cover 75 percent of the construction costs and to also provide a future subsidy of the line. Then in April of 1912, Hays died on the Titanic. The Grand Trunk Pacific lost more than its president, it lost its visionary and strongest supporter. As a result, the Grand Trunk did not become the economic hub of a great Northwest Coast empire as expected. Most histories of the time point to the loss of government support and the death of Hays as being the two death knells for the railway enterprise, but historian Frank Leonard believes it was a combination of smaller things that worked against the Grand Trunk. Leonard’s well-researched 1996 book, “A Thousand Blunders, a history of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway in Northern British Columbia” chronicles an endless litany of mistakes in the operation of the railway during its decade of independent operation. The title of the book was a pun on Hays’ frequent description of the Grand Trunk Pacific’s “road of a thousand wonders.” Frank Leonard goes so far as to call the Grand Trunk “one of the great failures in Canadian entrepreneurial history.” When the line opened in 1914, things did work out like Hays had anticipated. First of all, the Port of Prince Rupert did not develop into the world class operation that Hays had expected. Overall, the population of the northwest Coast grew steadily over time, primarily based on the development of the natural resources and the port did become a transshipment point for goods from central Canada. While the population did increase, there wasn’t enough traffic to keep the rail line solvent. The line also made a variety of mistakes in its dealings with both local governments in the area and with the indigenous peoples. Its labor relations were another factor in holding it back. Efforts to develop and market the line were also hampered by the outbreak of World War I in 1914. By 1919, it was clear the Grand Trunk was not able to pay its own way. On March 7, 1919, the line defaulted on its construction obligations to the federal government and the line was nationalized. A year later, it was placed under the management of the Canadian National Railways and by 1923, it was completely absorbed by the CNR. That was not the end of rail service to the Northwest Coast. For the next century, it gradually developed as the Port of Prince Rupert became a modest shipping point for Canadian products headed to the Far East. Rail service continues to the present day and much of its traffic is taken up by container shipments from the Far East through the Port of Prince Rupert. Hays’s vision is being accomplished a century after his death. It was a vision that was first realized in steel and iron, a century ago.

On the Web:

Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us

Publish A Letter in SitNews Read Letters/Opinions

|

||