Prohibition attempted to ban alcohol a century agoAlaska enacted a ban two years earlier, neither one workedBy DAVE KIFFER

January 26, 2019

"Hooch" and other spirits and beer have been the preferred "fuel" for the colonizing of Alaska since the Russians were making rot gut potato and corn vodka in stills in Kodiak and Sitka in the late 1700s and early 1800s. But at numerous times in Alaska's history, "demon rum" has been indeed demonized and made illegal to sell or possess. Most notably in the years after World War I when alcohol was illegal throughout the United States.

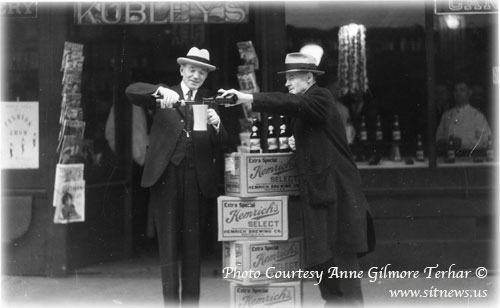

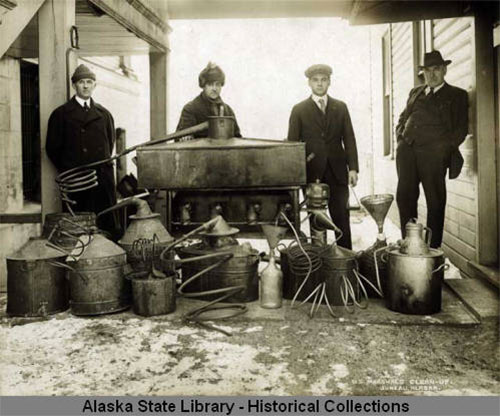

January of 2019 marks the centennial of ratification of the 18th Amendment, the Volstead Act, in 1919 which "forbade the production, sale and transport of intoxicating liquors" in the United States and its territories. Of course, none of the "bans" actually kept alcohol out of the hands of the Alaskan residents who wanted it. Alaska's remote location and tens of thousands of miles of coastline made it virtually impossible for the authorities - often called the "Revenuers" - from preventing it from arriving in the Territory. It also didn't help matters that Alaska's closest neighbor, Canada, was more than happy to help quench the parched throats of its Alaskan cousins. Ketchikan, in particular, was just 90 miles up the coast from Prince Rupert and there was an active "rum trade" between the two communities whenever Alaskan officials attempted to ban alcohol. Almost immediately after the purchase of Alaska in 1867, the US government moved to control alcohol in the territory. In 1867, the War Department - which had jurisdiction - prohibited the shipments of "spirituous liquors or wines" to Alaska. But by 1869, the Army itself was trying to make ends meet in Sitka (then the largest community in the state) by openly selling confiscated liquor back to the citizens, according to a 2015 story on alcohol in Alaska in the Fairbanks News-Miner. And within the next decade, the authorities had also given up efforts to stop residents from making their own "hooch." In 1877, nearly 5,000 gallons of molasses (a common ingredient in homemade alcohol) was brought into Sitka, more than enough "cooking" molasses for non alcohol needs for two decades! That year, the Treasury Department took over responsibility for administering Alaska. It immediately allowed the importation and manufacturing of beer and wine in the territory but said no to "distilled spirits." It also made it illegal to sell alcohol to Alaska Natives. That "open" policy lasted all of seven years. Pressure by national temperance campaigners led the federal government to once again ban alcohol in Alaska - except for "sacramental" purposes - when the first civil government was brought to the territory in 1884. But once again, Alaska's remoteness and a general disinclination to follow federal rules, led to an almost total lack of enforcement of the ban. By 1892, alcohol was again "legal" in Alaska. The young territorial government, looking for ways to pay for itself, developed some of the earliest processes for licensing and taxing alcohol sales. In 1899, the territory enacted a $1,000 license fee for all liquor dealers. It was reportedly the first "liquor license" program in the United States. By the 1910s, the national temperance movement that was leading to charge to ban alcohol nationwide had also reached Alaska. In addition to the normal anti-liquor arguments (its negative effects on health, personality and family life), alcohol abuse was creating significant problems in Bush Alaska, particularly amongst the Alaska Native population. A new law was proposed to make Alaska "bone dry" and it passed with the support of 62 percent of the voters. That vote took place in 1917, two years before federal prohibition was approved and went into effecf. Of course, prohibition did little to stop the use of alcohol in Alaska. Ketchikan residents soon learned they could make money by visiting Prince Rupert and bringing alcohol back into Alaska. So they did.

And that created a "cat and mouse" game between rum runners and the authorities that last for the next decade and a half. In the 1920s, the Ketchikan Chronicle was constantly reporting on local residents getting caught and fined for attempting to break the alcohol ban. It was during this period that Creek Street, Ketchikan's Red Light District, reached its nationally infamous peak. Several visiting journalists noted that Creek Street was one of the easiest places to get alcohol in America and the rum runners were blamed by state officials for contributing to what was called the "Wickedest City in America." Dealing with "rum runners" judicially was often a challenge in Alaska, as the residents in the communities generally supported the efforts to bring the alcohol in. The diaries of Judge James Wickersham, currently at the Alaska State Museum, show that he frequently made the journey from Juneau to Ketchikan in the 1920s to deal with "rum runner" cases and dispense justice. He often referred to them as "the bootleg trials" and it was clear he was frustrated by the inability of the local authorities in Ketchikan and Sitka to police their own communities. At various times, federal authorities would send officers in Ketchikan for "raids." But as soon as they left, it was business as usual. According the records of the Ketchikan's Federal Marshal, an average of 30 people were charged each year with attempting to subvert the alcohol bn. In the 1930s, there was a brief attempt to boost inforcement. In Ketchikan that meant that in 1932 148 people were charged with alcohol violations. But that number dropped back to 28 in 1933 when it became clear that the national ban was about to be overturned. Liquor entered the community by being brought up the coast in larger boats. Then those boats unloaded their cargo into smaller boats that then took the alcohol ashore. One popular location was near what it is now Bugge Beach about three miles South of Ketchikan. Oddly enough, a location on Pennock Island called "Whisky Cove" was named that decades before Prohibition, perhaps during one of the earlier alcohol "bans." Another popular area for dropping off illicit booze was Ward Cove, at least judging by the numerous stories in the Ketchikan Chronicle in which the local authorities kept finding shipments of alcohol in the Cove.

In downtown Ketchikan, the transporters of alcohol were forced to make their deliveries surreptitiously, often under the cover of darkness and frequently in a manner that took advantage of the fact that most of the Downtown and Newtown buildings were built on pilings. Even today, there are quiet a few Ketchikan buildings that have trap doors. During Prohibition, skiff loads of alcohol would be brought through the pilings at high tide and alcohol was lifted through the trap doors into the buildings. This was particularly common on Creek Street, where the brothels were kept supplied in this manner. Prohibition proved to be a spectacularly unsuccessful venture in the United States. By the late 1920s, alcohol use was skyrocketing (it was one of the few things that didn't seem to be affected by the Great Depression which began in 1929) and to make matters worse, the attempt to restrict it had led to organized crime taking over the largest role in importing and selling it to the American public. In 1933, the 21st Amendment to the Constitution was approved, rescinding the 18th Amendment. In Alaska, of course, it was a relatively easy transition as the bars and other purveyors who were operating "secretly" moved back out into the open again. Within weeks of the repeal of Prohibition, the Ketchikan Chronical was almost gleefully detailing the amounts of alcohol coming into Ketchikan and other Southeast ports on the weekly steamships. There remained, though, a ban on liquor sales to Alaska Natives which stayed in place until 1953. When Alaska became a state in 1959, there were still concerns in Bush Alaska about what liquor was doing to the smaller communities.

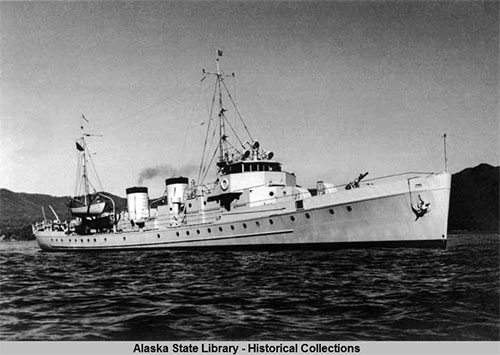

In 1979, the State Legislature revised liquor laws to allow communities to prohibit sale and importation of alcohol, creating the potential for "damp" communities where possession was allowed but sale or importation was not. In 1986, the law was further altered to allowed communities to ban the possession of alcohol, creating "dry" towns. As of 2015, there were approximately 40 "damp" communities in Alaska and 22 "dry" ones. Some communities, such as Bethel, have bounced back and forth between the three options (including "wet" which allowed alcohol importation, sales and possession). Some like Metlakatla - which was founded on the Anglican principal of abstinence from alcohol - remained "dry" for decades but was too close to a "wet" community, Ketchikan, to prevent speed boats - almost sinking under the weight of cases of alcohol - from transiting the oft-stormy Nichols Passage between the two towns. In December, 2018, a century after the death of Father Duncan, the tee-totaling Anglican missionary who founded the alcohol free community, town residents voted 302 to 152 to allow alcohol sales in the community for the first time. Prohibition also led to Ketchikan getting its first "modern" Coast Guard cutter. The USCGC Cyane was specifically designed to combat the seaborne "rum runners" who were making a mockery of the American alcohol ban in the late 1920s and early 1930s. The Cyane, WPC-105, was built in Seattle's Lake Union in the early 1930s. The 165-foot ship was specifically designed for speed, at that point 15 knots, in order to intercept "rum runners" along the West Coast. Unfortunately, by the time the Cyane was ready for deployment, in 1934, Prohibition was already over. She was sent to Ketchikan, where she served until 1950, when she was decommissioned and sold. The new owner turned her into a fish processor. Ironically the ship, now named the Can Am, ended up smuggling drugs into the US from Central and South America. Eventually the ship was seized and resold to a company that renamed it the Ruby E and turned it into a salvage ship, but then went backrupt and the ship was repossessed. By now it was the mid 1980s and the ship was sold for scrap, but instead of being scrapped it was turned into a artificial reef off Mission Beach in San Diego. The "Cyane" is a popular location for recreational divers.

On the Web:

Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us Dave Kiffer ©2019 Publication fee required. © Representations of fact and opinions in comments posted are solely those of the individual posters and do not represent the opinions of Sitnews.

|

|||||||