"Sincerely, Igloo..."

|

||||

Irvin Andrew Rubin Thompson |

Initially, Thompson’s body was not identified when it was removed from the partially submerged ship several months after the attack and was buried with other “unknowns” in mass graves in Hawaii, but eventually, thanks to dogged work by 87-year old researcher Ray Emory – himself a Pearl Harbor veteran – Thompson’s remains were identified in 2008 and reinterred at the Sacramento National Cemetery in Dixon, California. The Department of Defense chose that site because it was near the home of Thompson’s only known living relative, a distant cousin who requested anonymity.

Thompson had been born in Weehawken, New Jersey in 1917, but his family moved to Ketchikan in 1922, when he was five years old, according to a Ketchikan Chronicle story on December 16, 1941.

The Chronicle also reported that Thompson had graduated from Kayhi in 1935 and then spent a year at the University of Washington in Seattle before being appointed to the Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland.

Merta (Smith) Kiffer , my mother, lived across First Avenue from the Thompson family. She remembers Irvin who was tall, handsome and dark haired and three years ahead of her at Kayhi.

Irvin’s father, Andrew Thompson, worked for the city highway department. Kiffer also said that Mrs. Thompson was related the Schlais family which also lived on First Avenue.

Thompson's father was in Seattle with an unspecified illness, according to the Ketchikan Chronicle, when the Pearl Harbor attack occurred. Mrs. Thompson and the rest of the family joined him there in early 1942.

Kiffer said that Mr. Thompson died shortly afterwards and the Thompson family never returned to Ketchikan.

During his Ketchikan years, for grade school and junior high, Thompson attended Charcoal Point School, as did most children who lived north of Washington Street which was the city boundary until the early 1930s.

Charcoal Point school was run by the Federal Government and served many of the fishing industry families that lived in Ketchikan’s West End. It was located in a building – near the current site of the Alaska Marine Highway Terminal - that had been a “roadhouse” prior to Prohibition and many of the students who attended there, including my father, claimed in later years that the “Charcoal Point gang” was one of the “toughest” in town.

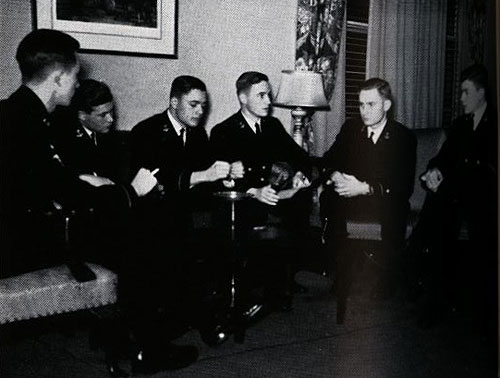

Thompson and members of the Kayhi Rifle Club 1935

Mr. Finley (Advisor), Lloyd Salt, David Dibrell, Stanley Bernhoft, Bill Shelton, Duncan Campbell, Mr. Schoel (Advisor), Helen Barton, Blossom Hewitt, June Hanson, Alice Caswell, Joy Kyle, Norma Kubley, John Spaulding, Anders Larsen, Mark Bussanich, Harry Elliott, Irvin Thompson, Rudd Smith, Robert Aiken.

Thompson had a very active Ketchikan High School career from 1932 to 1935, according to the 1935 Kayhi yearbook.

He was a member of the Rifle Club for three years and a member of the Student Body Association council and the basketball team his junior and senior years. The basketball team – called the Polar Bears back then - went 21-5 his senior year but lost to Wrangell and didn’t repeat as Southeast Champions, a title it had claimed Thompson’s junior year.

In Thompson’s senior year he was class president and won the school “Declamation” contest by “defeating” Wesley Sande with a speech entitled “Born Rich.” Thompson also had a small part in the class play, a murder mystery called “The Sixth Key” which involved a rich uncle and his five battling heirs.

More notably, Thompson was the salutatorian for the 21-member Ketchikan High School Class of 1935.

His senior motto was “There is great ability in knowing how to conceal one’s ability.”

In 1936, Thompson was accepted to the Naval Academy. He graduated in 1940 and was commissioned an “Ensign” in the United States Navy.

In the 1940 edition of the “Lucky Bag,” the yearbook of the Naval Academy, Ensign Thompson’s classes for the four years at the academy were well chronicled. But along with the dances, the training and the other events of academy life, the Class of 1940 was also well traveled with voyages to England, Madeira and up at down the East Coast from the Caribbean to the Arctic. Most notable were trips to both Germany and Japan where the cadets noted the military preparedness in both countries. Ironically, had Thompson entered the Naval Academy in 1935 rather than 1936, he would have taken one of his training “cruises” on the battleship USS Oklahoma. Instead, the midshipmen of Thompson’s class experienced battleship life on the USS Texas.

The Ketchikan home where Thompson lived on First Avenue in the 1930s. It was most recently owned by former city councilman Tom Coyne.

Photograph by Dave Kiffer

“Although he’s forever boasting of the advantages of rugged life in salmon country, this tall good looking ‘snake’ was born in New Jersey,” an anonymous writer noted on Thompson’s page in the 1940 Lucky Bag. “That probably explains why he’s forever bitterly disclaiming Maryland winters and seeking to rig a radiator around his bunk. His practical, varied sailing experience has been a ready help to those of us who are not so salty.”

The page history also noted that Thompson was not at the top of his class academically.

“ Academics, excluding a temporary lull over which he had no control (another drag), have been merely something between ketch trips and a game of basketball,” the Lucky Bag noted. “An amiable disposition and unusual common sense should find ‘Igloo’ a rich future, skoal!”

Because of Thompson’s Alaska heritage, he was called “Igloo” by everyone at the Academy.

The Lucky Bag – the name of which refers to a ship's ‘lost and found’ station - noted Thompson’s achievements as a four-year tour in the “Boat Club” and the title of “Ketch captain” his senior year. In his freshman year at the naval academy he was also a member of the “basketball squad.”

Photographs in the yearbook show Thompson sailing on an academy “knockabout sloop” and also attending a meeting of “ketch captains.”

Yearbook photograph showing Thompson sailing on an academy “knockabout sloop” |

There were approximately 350 graduates of the Naval Academy that year before Pearl Harbor. Nearly 70 members of the Class of 1940 would not survive World War II. Ten were killed at Pearl Harbor, seven on the Arizona and three on the Oklahoma.

After he was commissioned, Thompson was posted to the crew of the Oklahoma, along with several other Academy grads. It’s not clear exactly when he joined the Oklahoma crew but he was already a member when Ensign Ed Vezey joined the ship in early April of 1941.

On July 11, 1941, Thompson wrote a letter to his Annapolis roommate, Joe Rinschler who was from New York City. “Bos’n Joe” Rinschler was also a four year member of the “boat club.” Rinschler would go on to name his first born son after his former roommate.

The letter remained in the possession of the Rinschler family up until this fall, when one of Rinschler’s sons, Birmingham, Michigan Mayor Gordon Rinschler sent it to the Ketchikan-based Tongass Historical Museum. The letter gives an interesting view into Thompson’s shipboard life and how members of the US military were preparing for the war that they knew was coming in the months before Pearl Harbor.

“Dear Joe, “the letter begins. “I have been properly chastised for my long period of no letters that now I’m almost ashamed to write. You know me and my writing Joe, it’s just sort of natural for me to go along for months without even dropping a line to anyone, even my best friends.”

Thompson then mentioned a girl that he had apparently met before he graduated from the Academy.

“Of course, there being one exception to the rule, I still write Isabelle very regularly,” he wrote. “I saw Bloody and Johnny a few days back and they both got into me for not writing you and then yesterday your letter came. I am sorry Joe but you will just have to let it go as part of ‘Igloo’s’ makeup.”

He then mentioned Rinschler’s wife.

“Johnny recommended a very good eating place if I was ever in New York so I guess Norma is feeding you well enough,” he continued. “He said she was a real good cook… but I’ll have to wait and judge for myself, ‘tho I do remember she makes good cakes. They always say if you can’t marry money, marry a good cook.”

He then goes back to his girlfriend.

“I don’t know what the hell I’m going to do” Thompson wrote. “Isabelle hasn’t any money, & can’t cook either. Guess I’ll just have to be the subject for her experiments. And then if worst comes to worst I can always eat a big meal before I go ashore so maybe I won’t die before she learns how to cook. Things are still going along smoothly with us despite the fact I haven’t seen her since a year ago in June.”

Thompson, far left, meeting with other officers in the USNA "boat club"

Photo courtesy 1940 edition of the Naval Academy's Lucky Bag

She was obviously still on his mind, despite his long deployment.

“Some of the boys were lucky and went back to the states but we've been out here since last October,” Thompson wrote. ”We should go back one of these days before long and I expect to get a few days leave and go back and see her. Even 'tho you don't think me capable of loving just one girl I'm still just as much in love with her as ever and I haven't seen her for over a year. You never had that experience did you… you're just too dammed lucky is all I got to say… both of you.”

Then Thompson turned his attention toward shipboard life.

“You were really smart not to sign up for the Reserve last year, just think of how much better off you will be after all this is over and they throw out all the excess of Officers again,” Thompson wrote Rinschler. “We've certainly have had our fill of these ‘new reserves,’ most of them aren't worth the powder to blow them to the well known place. It's quite a problem on the ship here cause there are more ‘90 day wonders’ than there are academy men. But neither our class nor '41' takes any stuff from them even 'tho some of them technically rate 41.”

Of course, Thompson was also limited in what he could tell Rinschler.

“I'd like to write you all about what we are doing out here but we have sort of a self-censorship and aren't supposed to write about our works,” he wrote. “All I can say is that it's practically on a war time basis and at times it's really hell. When we are at sea it's practically G.Q. (general quarters) all the time and even up until ten in the evening. I've been standing top watches for a month or so now all except when we are in special maneuvers and at times it's quite a strain on you. This ship is about the most advanced as far as top watches for our class goes and even 'tho I'm glad of it, it's still quite a responsibility for a year old Ensign at night on a darkened ship.”

He was also having “issues” in his main battle station.

“I'm doing all right I guess all except for a few little points… one of them being the assistant main Battery Officer with whom there is a mutual dislike,” Thompson wrote. “I have control of the main battery in plot at various times & he doesn't seem to appreciate my telling him his mistakes over the main phone circuit. But as far as I can see he's practically a Lt. Com. and shouldn't have to be told about mistakes by a Junior Ensign. He should know better than to make mistakes. I saw my 6 month fitness report & had a very good one too. My lowest mark was a 3.3 and all the rest excepting one 3.5 were all above 3.7. So if I can keep it up I may make it yet.”

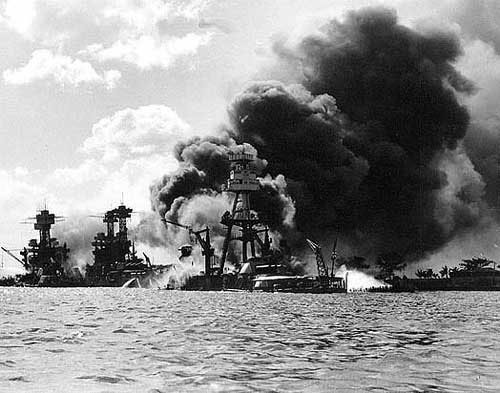

View looking up "Battleship Row" on 7 December 1941, after the Japanese attack.

Pearl Harbor Attack, 7 December 1941

USS Arizona (BB-39) is in the center, burning furiously. To the left of her are USS Tennessee (BB-43) and the sunken USS West Virginia (BB-48).

Official U.S. Navy Photograph, from the collections of the Naval Historical Center.

Thompson did note that he was able to fit in a little bit of a social life.

“I've been going ashore quite a bit lately not because I enjoy it so much but I'd go nuts out here if I didn't find something to do,” he wrote. “I've been dating various girls out here but it's just for something to do, my heart is still very much in Tennessee. And besides, if I didn't date, I'd get in a rut & wouldn't know how to act around girls, can't let that happen can I. I don't drink much of anything except to go on my ‘quarterly binge’ which I always regret the next day. This is the worst place in the world for a hangover.”

Then it was time to sign off.

“Well you old bum I got to go now but will try & do better about writing in the future,” he concluded. “Give my love & best regards to Norma. I hope I'll be able to taste some of her cooking before long. So long kid. Sincerely, Igloo.”

Ensign Ed Vezey knew Ensign Thompson on the Oklahoma from the spring of 1941 up until Pearl Harbor. He said, in a series of emails from Colorado in December of 2008, that he often talked with Thompson in the junior officer’s wardroom. He confirmed that Thompson’s battle station was in the main battery (gun) control area of the ship.

Vezey remembered a specific visit that the Oklahoma made to the San Francisco not long before Pearl Harbor.

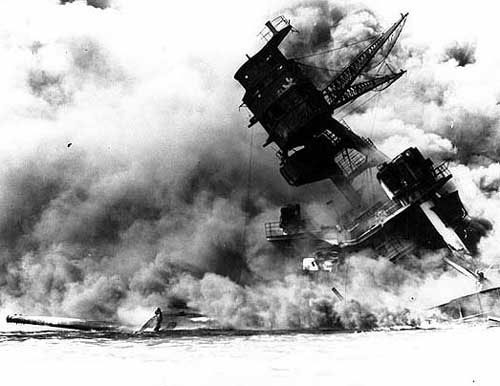

USS Arizona

Pearl Harbor Attack, 7 December 1941

The forward superstructure and Number Two 14"/45 triple gun turret of the sunken USS Arizona (BB-39), afire after the Japanese raid, 7 December 1941. The foremast is leaning as a result of the collapse of the hull structure below its front leg, following the explosion of the ship's forward magazines.

Official U.S. Navy Photograph, from the collections of the Naval Historical Center.

On August 22, 1941, the Oklahoma left Pearl Harbor for the naval base at San Pedro, California, but – according to the official history of the “USS Oklahoma, BB-37” a book written in 2008 by Jeff Phister, Thomas Hone and Paul Goodyear and published by the University of Oklahoma Press, the battleship encountered a massive storm en route that killed one sailor (who was washed overboard) and injured several others. The ship began to vibrate very heavily and the crew discovered damage to the starboard engine shaft.

Instead of going to San Pedro – near Los Angeles – the ship was sent to the Navy repair yard at Hunter’s Point in San Francisco Bay. She would be under repairs for more than a month and that led to the “adventure” that Vezey remembered.

“Igloo Thompson was a really great guy, always pleasant and friendly,” Vezey wrote in 2008. “…Igloo and I were just bumming around the town (San Francisco) – no particular plan – just a couple of guys with no particular destination –SF lent itself to that mode in those days.”

He said that the two sailors were in a bar and began talking to a middle-aged woman.

“She was a bit in her cups,” Vezey wrote. “In the course of the evening she told us she had an invitation to dinner at the home of a nice widow lady who had a lovely daughter, and in due time she invited us to join her – imagine. Well, why not? She gave us the address and at the appointed hour Igloo and I caught a taxi and headed out – quite sober, mind you. Igloo was not given to excess and I was following his good example.”

The hostess was surprised by their appearance at her home.

“You can imagine the consternation of the hostess with two totally strange ‘sailors’ met in a bar univitedly coming to her home,” Vezey continued. “Her relief was palpable when two clean cut young officers of the line showed up at her door and she was very gracious. Turned out she was ‘babysitting’ this lush as a favor to a friend. I still remember the names of our hostess and daughter, Mrs. E.B. Palmer and her, yes, lovely daughter, Alice Hemmings. We had a lovely evening and stayed late. Crazy? Yes, but when you are young and a bit bored and feeling like you can lick the world, why not?”

And that wasn’t the end of the adventure.

“In turn, Igloo and I invited Mrs. Palmer and Alice out to dinner on the ship and they accepted which makes them as adventurous as we were,” Vezey wrote. “The sight of a beautiful battleship in dry dock is pretty doggone impressive and the guys in the Junior Officer’s wardroom made the gals feel like royalty – Igloo was disarmingly boyish and charming anyway and it was a great time. They were a bit overwhelmed with the size and the spotless cleanliness of a ship that size.”

Vezey was a reserve officer and even though Thompson had earlier written to Rinschler about his dislike of the so-called “90 day wonders,” he clearly treated Vezey well.

“A measure of Igloo’s character was the fact that he was an Academy graduate and I was a reserve officer – most Academy grads had some measure of disdain for us reserves, but there wasn’t even a hint of that in Igloo’s attitude toward me and we were good friends,” Vezey wrote. “Igloo was a gentleman to the end and deferred to me in continuing the friendship with young Alice, and had we not gone back to sea shortly and into WW II with its stress, that evening might have ended in marriage for me. If my memory serves, Igloo already had a least casual romantic interests. After the war started I tried to find out what his family connections were but to no avail.”

On December 7, the Oklahoma was back at Pearl Harbor, still engaging in the patrols that Thompson noted in his earlier letter. In fact, it had just come on the evening of December 6 from a patrol. An inspection was scheduled for the next morning and as a result, many of the normally closed water tight doors and compartments were open as the crew rushed to make the ship “shipshape.” Most of the ammunition was also stored well below decks away from the guns. The opening of the hatches and watertight doors would later be considered part of the reason the battleship capsized so quickly.

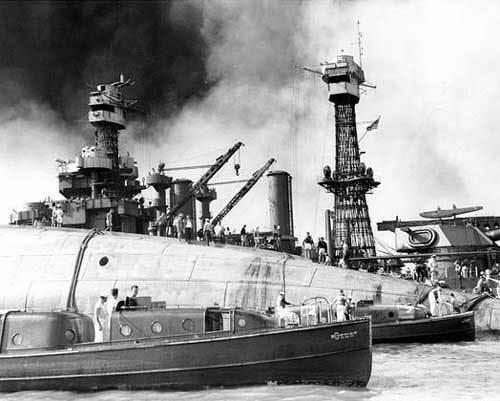

Capsized Hull of USS Oklahoma

Pearl Harbor Attack, 7 December 1941

Thompson was lost in the sinking of the battleship Oklahoma.

Rescue teams at work on the capsized hull of USS Oklahoma (BB-37), seeking crew members trapped inside, 7 December 1941. The starboard bilge keel is visible at the top of the upturned hull. Officers' Motor Boats from Oklahoma and USS Argonne (AG-31) are in the foreground. USS Maryland (BB-46) is in the background.

Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives.

When the Japanese carrier based dive bombers and torpedo planes appeared in the sky over Pearl Harbor at 7:55 am on December 7, 1941, the Oklahoma was hit several times almost immediately, including at least four and possibly five torpedo hits. Within 15 minutes it had rolled over, trapping more than 400 crew members inside the ship. One was Ensign Thompson.

“How did Igloo die?” Vezey wrote. “I don’t know for sure – I think his battle station was in the Main Battery gun control which would have put it in the bowels of the ship within the armored ‘box’ which protected the vitals of the ship. In that case he had little or no chance of escaping since the ship capsized in just a few minutes. Most of those stationed below could not escape and most of the 429 casualties occurred there.”

Of the several hundred sailors trapped inside the Oklahoma, about 30 were rescued, some up to 30 hours later when holes were cut in the hull of the ship. One of the rescued sailors, Stephen Bower Young published “Trapped at Pearl Harbor, Escape from the Battleship Oklahoma” in 1991.

Vezey remembers the events of December very clearly, even amid the chaos.

“I was in my bunk (two junior officers in a room) as was my roommate Ens. Frank Flaherty and (we) were trying to decide whether to go swimming before or after breakfast,” Vezey wrote in a December 24, 2008 email. “The General Alarm decided that and Frank left for his battle station in the #1 14 inch gun turret where he died and received the Congressional Medal of Honor for saving most of his crew at the cost of his own (life).”

Irvin Thompson Mountain on Gravina

Photograph by Dave Kiffer

According to the US Navy’s Medal of Honor website, Flaherty received the commendation “For conspicuous devotion to duty and extraordinary courage and complete disregard of his own life, above and beyond the call of duty, during the attack on the Fleet in Pearl Harbor, by Japanese forces on 7 December 1941. When it was seen that the U.S.S. Oklahoma was going to capsize and the order was given to abandon ship, Ens. Flaherty remained in a turret, holding a flashlight so the remainder of the turret crew could see to escape, thereby sacrificing his own life.”

Vezey said that his battle station during the attack was at the anti-aircraft gun control about half way up the foremast. He didn’t have much time to prepare.

“As the ship rolled I followed it around like burling a log and eventually swam to the USS Maryland,” he wrote. “In less than 15 minutes we went from a couple of carefree kids to dead or in the water. Truly a pivotal point in the lives of the survivors. People ask me if I was afraid during the attack and the answer is ‘no.’ The reaction was one of intense fury – a fury that boils up all over again as I write this and think of all the really great guys who were robbed, no, murdered and deprived of the privilege of living out their years.”

Editor's Note:

In Thompson's honor, flags were flown at half-mast throughout Alaska on Dec. 21, 1941 by proclamation of Territorial Governor Ernest Gruening.

Related Article:

Irvin Thompson Reburied In California; Ketchikan War Hero's Remains Were Identified After Over 60 Years By DAVE KIFFER - A Ketchikan man, who was Alaska's first casualty in World War II, is a little closer to home after being reburied last month in a veteran's cemetery in California. - More...

Thursday - December 18, 2008

On the Web:

More Columns by Dave Kiffer

Historical Feature Stories by Dave Kiffer

Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us

Publish A Letter in SitNews Read Letters/Opinions

SitNews ©2011

Stories In The News

Ketchikan, Alaska

Articles & photographs that appear in SitNews may be protected by copyright and may not be reprinted without written permission from and payment of any required fees to the proper sources.