German POWs helped dismantle SE Alaska’s ‘White Elephant’By DAVE KIFFER February 17, 2015

There are also plenty of stories about heroic Alaskans who fought in the war, like Ketchikan’s own Irvin Thompson, who died on the USS Oklahoma at Pearl Harbor. But relatively few Alaskans are aware that a large group of German prisoners of war were held in Southeast Alaska for several months towards the end of the war. They were tasked with taking apart a secret military installation that should probably never have been built it the first place.

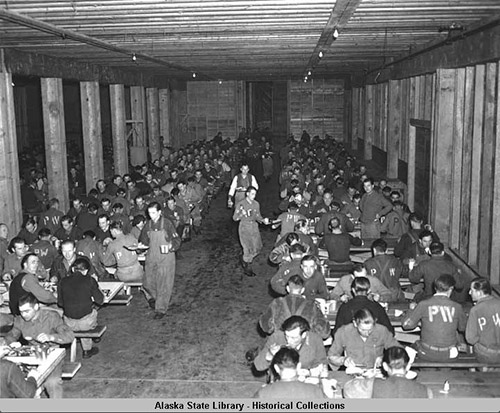

Prisoners of War Camp (German prisoners) Excursion Inlet, Southeast Alaska. August-November, 1945. Men eat in the PW mess hall, 1945. Excursion Inlet. German prisoners of war, 1933 Service Command Unit - mess hall filled with men. The site for the terminal was Excursion Inlet 25 miles west of Juneau, on the west side of the Chilkat Mountains near Gustavus in what is now Glacier Bay National Park. Natives had used Excursion Inlet for camps generations prior to 1900, according to Southeast historian Pat Roppel. Roppel wrote in the Capital City Weekly in 2010, that two salmon canneries were established about three miles apart in the inlet in 1908. In 1935, Pacific American Fisheries (PAF) closed its cannery and purchased the slightly larger one owned by Astoria and Puget Sound Canning Company. Then in early 1942, representatives of the United States government arrived in the inlet and began poking around, examining the terrain and measuring the water depth at various locations. Roppel notes that most of the documents regarding the “project” in state and federal files were marked “secret” and were classified for many years after the war. Yet, the cannery continued to operate and local residents were allowed to continue to use the inlet, meaning that most people knew the location of the "secret" facility.

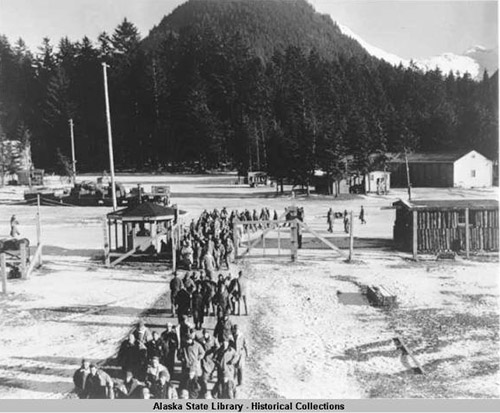

Prisoners of War Camp (German prisoners) Excursion Inlet, Southeast Alaska. August-November, 1945. The POW's return to the stockade at noon, 11-7-45. It was an expensive attempt by the US Army to “shorten” the supply lines as it attempted to dislodge the Japanese from Kiska and Attu, the two Aleutian Islands Japan had invaded in June of 1942. According the article “German Prisoners of War in Alaska” in the Autumn, 1984 edition of "The Alaska Journal," the Western Defense Command authorized construction of the “Alaska Barge Terminal” at Excursion Inlet in July of 1942 near the PAF cannery site. “The U.S. strategy was to supply Alaska by (quicker)barge via the Inside Passage from Seattle and Prince Rupert to Excursion Inlet, where goods would be trans-shipped to oceangoing vessels and shuttled to the Aleutians,” the article noted. At the time, there was concern that Japanese submarines could cause significant disruption to the supply lines in the same way that German U-boats had nearly cut of England in the early stages of the war. The same concerns led the U.S. government to simultaneously spend tens of millions of dollars to building the Alaska-Canada Highway.

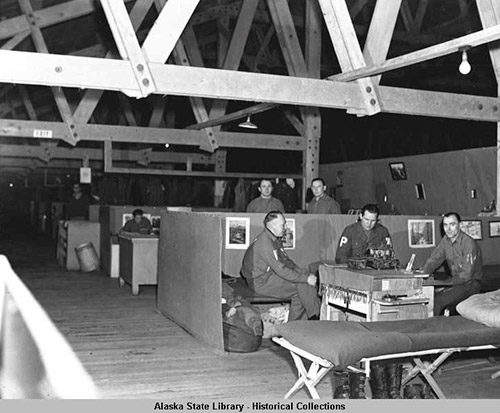

Prisoners of War Camp (German prisoners) Excursion Inlet, Southeast Alaska. August - November, 1945. Much of the construction took place on land owned by PAF, which was not compensated or even asked if it objected. Facilities included more than a half million square feet of open storage area, a tank farm with a fuel capacity of more than 3 million gallons, three 1,000 foot docks, a 200 bed hospital and quarters for nearly 4,000 soldiers. There was dock space for six barges, nine ocean-going vessels, two ammunition ships and two oil tankers. Unfortunately, by the time everything was complete in November of 1943, the Japanese had already been driven from Attu and had abandoned Kiska. The terminal was no longer needed and was immediately mothballed. “As the war neared an end in 1945, the question of what to do with the huge military base had to be decided,” the Journal noted in 1984. “There was no apparent postwar, civilian need to a barge terminal in the middle of nowhere and the project had become an embarrassment.” An article appeared in the New York Times in the spring of 1945, officially lifting the cloud of secrecy on what the Times called “a giant white elephant.” In response, the Army came up with a new plan. It determined that 12 million board feet of wood could be salvaged from the facility, in addition to $3 million worth of other supplies. With the war still raging on both the European and Pacific fronts, manpower was at a premium. But there were approximately 400,000 German prisoners of war in the United States, including several thousand in Washington. Although there were some concerns expressed about how the Geneva Convention discouraged the use of POWs for work projects, it was decided to send 700 prisoners from Seattle to Excursion Inlet to tear down the unused barge facility. The POWs would be compensated for their work. Initially, the Army planned to send even more POWs to Excursion Inlet, but strong opposition from Territorial Congressional Delegate E.L. “Bob” Bartlett and Territorial Governor Ernest Gruening limited the number of POWs. Bartlett and Gruening reflected the general concerns from most Alaskans that even through the war had caused a labor shortage the POWs might be put to work on other projects and take away jobs that could go to Alaskans.

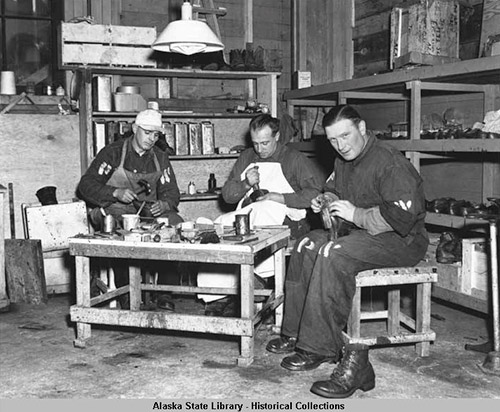

Prisoners of War Camp (German prisoners) Excursion Inlet, Alaska. August-November, 1945. Three PW's at work in the shoe repair shop, 1945, Excursion Inlet , Southeast Alaska. In general, under the Geneva Convention rules, the prisoners were treated very well at Excursion Inlet. In the four months they were “employed” dismantling the facility, only two escapes were reported. One prisoner returned within hours claiming he was “cold” and afraid of bears and wolves in the nearby woods. The second escapee was caught a short distance away from the base. Roppel reported in 2010 that the PAF cannery continued to operate all through the war, canning 50,000 cases a year while the barge terminal was being built and sat idle. After the war, the federal government offered the site and the remaining buildings to the public but there were no takers. Eventually, one of the larger buildings was dismantled by the Alaska Native Brotherhood and Sisterhood of Hoonah and taken to that community where it was rebuilt as a meeting hall. Some of the remaining structures eventually reverted to use by the cannery, especially after a 1948 fire damaged or destroyed a large portion of the existing cannery. The forest also reclaimed much of the developed uplands. Today, some 70 years later, it is hard to tell that secret military facility even existed. In a recent post script to the barge terminal story, one of the families that was living in Excursion Inlet before the facility was built was finally given. in 2001 , title to nearby land. According to a 2001 story in the Juneau Empire, Pete Duncan and his family were living in Excursion Inlet, when the US Army came to take possession for the base. “When the Army came to bulldoze Pete Duncan's original home site in 1943 it found two American flags on the property, representing Duncan's two sons who were serving in the military, and a determined Pete Duncan,” Al Duncan told the Empire. “The military agreed to a land trade for a new site several miles away.” The Duncan family relocated to the new site and then, in the 1970s, realized it had no deed for the new property. Finally, in 1999, Senator Ted Stevens arranged for federal compensation to the Haines Borough to cover the 20 acres of land that the Duncan family was living on. There is no official confirmation that any of the Excursion Inlet POWs ever returned to the Alaska, but there were anecdotal reports in Juneau of groups of German tourists chartering boats to Excursion Inlet in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

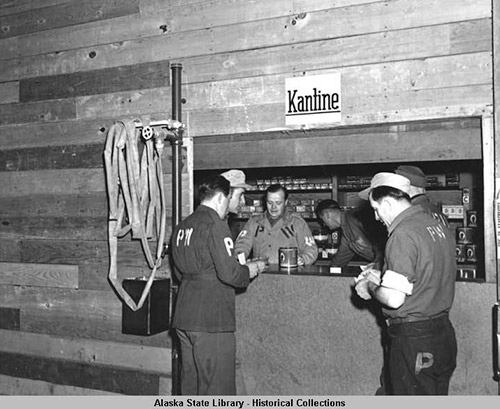

Prisoners of War Camp (German prisoners) Excursion Inlet, Southeast Alaska. August - November, 1945. German prisoners of war patronize their canteen or "kantine." Excursion Inlet, Alaska, 1945.

In 2013, a 1-cent “Kantine” chit turned up in Alaska and was reported on in 2014 in the Alaskan Token Collector and Polar Numismatist, published by Alaska Rare Coins in Anchorage. The “chit” which was used at Excursion Inlet in 1945 is believed to be the only one in existence. Its value has not been determined. “Chits” were traditionally issued in booklets in various donations, according to Lance Campbell in his book “Prisoner of War and Concentration Camp Money of the 20th Century. Although, the history of the camp is not particularly well known, Anchorage writer Don Reardon has written a screenplay called “Ghosts of the Camp” that is set in the Excursion Inlet POW camp. That screen play can be viewed at http://www.stage32.com/sites/stage32.com/files/assets/screenplay/927/

Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us

Publish A Letter in SitNews Read Letters/Opinions

|

|||