Charcoal Point: From One R to the Three RsPre-Prohibition roadhouse became school For children of Ketchikan's north suburbsBy DAVE KIFFER May 26, 2021

Ketchikan High School has operated for more than a century in two locations, Main School Hill and Fourth Avenue in the West End. White Cliff Elementary was open from 1927 to 2003 before it closed. It is now the Ketchikan Gateway Borough office building. Both Schoenbar Middle School and Houghtaling Elementary schools have been open since the early 1960s when Ketchikan was in rapid expansion after the opening of the Ketchikan Pulp Company Pulp Mill. But one of the shortest-lived schools seems to have had enough notoriety that some 90 years after it closed, it lives on in the community memory. From the beginning, Charcoal Point School was notorious.

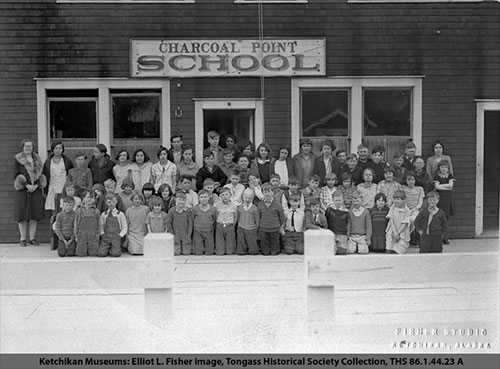

It was located outside the northern Ketchikan city limits, which was Washington Street in the 1910s. As a result, it was run by the Territorial Government and not the local school district. Most of the children who attended the school were from working class fishing families that lived in the neighborhood surrounding Bar Harbor, north of town. Many didn't even speak English before going to school. And most notably, it was in a building that, prior to Prohibition, was a "roadhouse." "I went to Charcoal Point School, which used to be Dynamite Joe's old roadhouse,"" the late Ralph "Scooty" Homan said in the 1995 Ketchikan oral history book "Clams on the Beach, Deer in the Woods. "The government came in during Prohibition and took it away from him. Dynamite Joe was selling booze, ya know. That was quite a trade in those days and Dynamit Joe, ya know, he was the worst." Dynamite Joe himself appears lost to Ketchikan history, with only the references to his "roadhouse" being used as a school remaining. There were several roadhouses located in Ketchikan as the Tongass Highway began snaking both directions along the Tongass Narrows away from the Downtown Ketchikan in the early 1910s. The roadhouses offered rooms, meals and alcohol, at least prior to the Alaska Bone Dry Act of 1917 taking effect. That was two years before the national Prohibition Law went into effect. Interestingly enough most of the "roadhouses" were located near areas that rumrunners from Canada used to drop off the supplies they brought to Alaska, even before Prohibition. There were roadhouses near Mountain Point, the Homestead and Ward Cove, as well as Dynamite Joes, which was located where the Alaska Marine Highway Terminal is now. Although the school opened in 1920, it was in February of 1916 that the "Charcoal Point People" officially petitioned the territorial government to provide for their children. According to Feb. 3, 2016 story in the Ketchikan Daily Progressive Miner, 44 "bona fide" residents of the Charcoal Point "school district" noted that there were 30 school age children in the area. It placed the area population at more than 350 people and noted that the education service was mandated based on a 1915 Act of Congress. The proposal was approved within a month, but it is unclear why it took four more years before the roadhouse was requisitioned for the purpose. Newpaper stories from the time indicate that a lot of effort was going into finishing what was then called the "Charcoal Point" road which was connecting the area from Tongass and Washington Street to "Charcoal Point" which was near the current intersection of Carlanna Avenue and Tongass. It is possible that the officials waited until the road was complete to open the school. According to information from the Tongass Historical Museum, the roadhouse had a dance floor and a player piano. The piano remained when the building was converted into a school in 1920. "There was a central fireplace for heating, two classrooms downstairs and three upstairs," the museum document notes. "A fenced in back porch which jutted out over the water served as a playground. On a good high tide you could feel the logs thumping against the underside of the building." Homan attended the school in the late 1920s toward the end of its lifespan. "In Charcoal Point, we had three rooms and three teachers, all eight grades, each room had two or three grades and you had to hear the same stories over and over again for three years," Homan said in 1995. "They had wood stoves and we went and got the wood and kept the stoves going. Just an old platform outside to play on. We put up a basket and played basketball rain or shine. The beach between there and Sunny Point was tide flats and we took all the rocks off at low tide and played baseball at low tide. We only had one ball and if you knocked the ball into the bay, you had to go out and get it." Maxine Robertson, who taught the school for one year, 1932 to 1933, before it was closed remembered it as "community school" according to the Museum records. "Holidays were celebrated there," she said. "People in the neighborhood were proud of the school, it felt like a big happy family." Many of the families were Norwegian immigrants to the community and the children had to learn English when they came to school, along with reading, writing and arithmetic. Censuses in the early 1920s estimated that nearly 500 people lived in the area between Washington Street and Carlanna Creek. Some of the area had been early mining claims, particularly around Carlanna and Hoadley creeks. In 1919, the Ketchikan Shingle Mill, originated by Ott Inman on Creek Street, moved to the Charcoal Point area, south of the school, further boosting the population in the area. There were also a handful of small ship building and repair businesses in the area. A foundry and a tannery were also located in the Charcoal Point area in the 1920s. One business that apparently was not welcome in the area, according to a 1924 story in the Chronicle, was a fish meal fertilizer plant. The paper noted a petition by residents that opposed the plant because of the smell and the offal that it would generate "would cause irreparable injury to the residents and property of the neighborhood as well as to the general welfare of the entire city of Ketchikan." The fertilizer plant - known locally as the Stink Plant - would eventually be located in then far away Ward Cove. In those days, school attendance was only required to eighth grade and most of the students stopped after that year. But for those that wanted to continue, the territorial government paid for them to continue on at Ketchikan High School downtown. According to the museum info, the Charcoal Point had 90 students and five teachers in 1932-33. But in the Spring of 1933, the area residents voted to extend the city limits from Washington Street to what was then Smiley's Cannery, which was located just south of what is now Wolf Point. Charcoal Point students were then sent to White Cliff School. Sometime before 1940, a storm damaged the building pilings, and the old roadhouse/school was torn down. But its memory lived on. In oral histories from the 1990s, two future mayors, Ted Ferry and Ralph Bartholomew - who attended other schools in the community - both noted that the "kids" from Charcoal Point had their own "gang" and were some of the toughest ones in the area. My father, Ken Kiffer, also attended Charcoal Point and agreed that having to carry wood to the school every day for the stove made the students "tough." He also noted that most of the kids at the school learned to swim to chase balls and other objects that frequently went off the back deck into the water. It wasn't just the "gang" that gave the school notoriety. Its entire history coincided with Prohibition and even though the roadhouse was no longer operating, bootleggers continued to use the Charcoal Point area to drop off shipments. Ken Kiffer said it was not unusual for the students to find liquor bottles on the tide flats near the school or carried by the tides up under the building. Several times, bootleggers were apprehended near the school according to stories in the Ketchikan Chronicle in the 1920s. In a 1926 story in the Chronicle, Charcoal Point was called the "wild west" of Ketchikan. The article called for increased "territorial resources" to combat the "lawlessness of the area." It made no mention of the school.

On the Web:

Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us Dave Kiffer ©2021 Publication fee required. © Representations of fact and opinions in comments posted are solely those of the individual posters and do not represent the opinions of Sitnews.

|

|||