Anyox: Once Ketchikan’s Rival;

Now just another ghost town

By DAVE KIFFER

August 24, 2013

Saturday PM

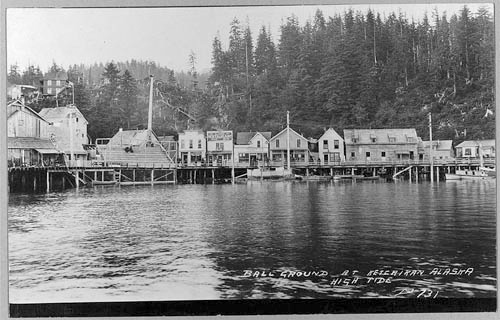

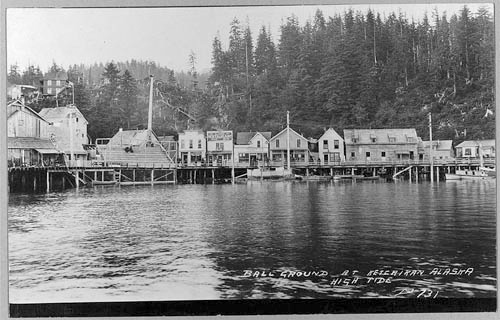

Ketchikan, Alaska - Most longtime residents of Ketchikan have seen the familiar scenes of Ketchikan baseball players playing on the tide flats, now the Thomas Basin harbor, in the early decades of Ketchikan’s existence.

The games were tide dependent and more than a few were “called” when the tide came in. Many local families have forbearers who played in those games until a town ball field was built near upper Ketchikan Creek on land owned by local politician Norman R. “Doc” Walker. In the late 1920s, Thomas Basin was dredged to create fill for the new Federal Building and the harbor was developed.

Ketchikan's old baseball ground under water at high tide [early 1900s]

Forms part of: Frank and Frances Carpenter collection (Library of Congress).

Gift: Mrs. W. Chapin Huntington; 1951.

Historic Photo Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division - Washington, D.C.

Those early tide flat games, which peaked in the late 1910s and early 1920s, were primarily against teams from Ketchikan’s familiar rivals, Juneau, Sitka and Prince Rupert. But one of the more frequent visitors came from a community that no longer shows up on the maps, although in the early part of the 20th Century, it was bigger than Ketchikan: Anyox, British Columbia.

Anyox was located on Observatory Inlet, about 37 miles southwest of Stewart, British Columbia, 40 miles north of Prince Rupert and not far from the US-Canadian border. Observatory Inlet was so named by British explorer George Vancouver in 1793 because he set up an observatory there to calibrate his chronometers.

The Anyox area of Observatory Inlet is known for a higher than normal tidal range, sometimes approaching 25 feet. In his journals, Vancouver reported that on July 24, 1793, a group of his men camped on a beach in the area some 20 feet above the apparent tide line but at about 2 a.m. “sea water flowed into their tents and they were forced into the boats.”

In the late 1800s, copper and other minerals were discovered in the area and a decade later, the boom town of Anyox came into being. Anyox – the name reportedly means “hidden water” in Tsimshean – was a company town owned by the Granby Consolidated Mining, Smelting and Power Company Ltd.

Writing in the 2007 edition of the Canadian journal “Mineral Exploration”, Julie Domville said the community “played a key role in the early development of northwestern British Columbia.”

“A large, modern and self-sufficient town was built around the mine to accommodate, and care for, a large workforce and their families,” Domville wrote. “Two electrical generating powerhouses were built, one coal fired and the other hydroelectric, to operate the mine, mill and smelter complex.”

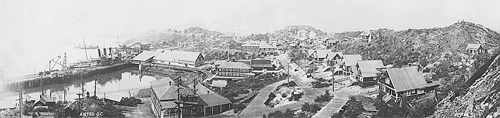

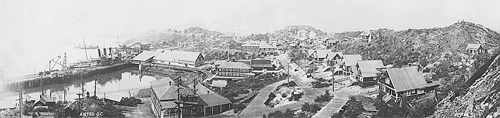

Anyox, British Columbia, 1911

Source: Courtesy City of Vancouver municipal archives image A31916

Author McRae Brothers

Photo courtey Wikimedia Commons.

Domville noted that 21 million tons of copper ore was mined between 1914 and 1935 resulting in 321 thousand tons of copper, 206 thousand ounces of silver and 121 thousand ounces of gold.

“Considering the remoteness of the mine and the technologies available at the time, this was a remarkable achievement and an indication of the quality of the engineering, construction and management provided by Granby,” Domville added.

Marie Elliot, writing in The Canadian Encyclopedia, noted “at the peak of operation, it was one of the largest producing copper mines and smelters in the British Empire.”

The best descriptions of life in Anyox come from British Columbia journalist Pete Loudon, who lived in the community for 10 years between 1925 and 1935 when he was a child. He wrote a book called “Anyox: The Town That Got Lost” in 1973.

The book describes a life that is familiar to many who grew up in small towns along the coast where the wilderness was on the doorstep and children grew up remarkably self-sufficient, having to “make their own fun” because the community lacked many of the modern amenities of those in more urban areas.

But Anyox was, in many ways, a more industrial area than most north coast communities because of its large smelter operation. Loudon noted that most of the residents of town came from old “mining stock.”

“Anyox was mainly peopled with transplanted Scots, Welshmen and mining men from the north of England, whom we called Geordies,” he wrote. “If there was a power block in town, I guess the British formed it. But there was another large section of the community whose roots lay in continental Europe and they were generally and shamefully referred to as the ‘foreigners.’”

The town of Anyox was divided into three sections, split by Falls Creek and Hidden Creek (reportedly so named because a group of Tsimshean warriors had used it to avoid a Haida raiding party in the late 1800s). Falls Creek was between the smelter and the largest residential area, while Hidden Creek divided that residential area from the main business area on Granby Bay. The business area had a wharf that was nearly half a mile long, according to a 1935 story in the Vancouver Province by F. M. Kelley.

Kelley wrote that three prospectors from Port Simpson; W. Collison, A. Flewin and D. Robinson camped, in 1898, on what was later named Granby Bay to explore reports of a “mountain of gold” supposedly only known to the local Nass River First Nation. They, and those that followed, did not find El Dorado. The area did yield some gold and silver, but it was copper that made Anyox.

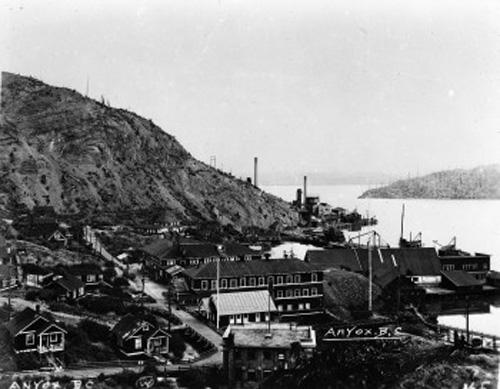

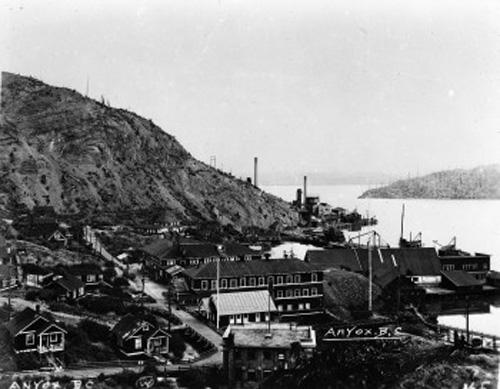

Anyox, BC 1934

View of Anyox, BC from the hill looking toward the water,

homes, buildings, roadway and smoke stacks

William W. Wrathall, Part Of: Wrathall Photo Finishing Collection

Photo Courtesy Prince Rupert City & Regional Archives

By 1912, Granby had begun building the community, which quickly grew to a population of 2,000 by 1914. Population peaked at between 2,500 and 3,000 people in the early 1920s. A forest fire destroyed much of the community in 1923, but the town was quickly rebuilt. The remote location’s high production costs and the economic depression of the 1930s combined with low copper prices to cause the company to end operations in 1935.

By 1928, Loudon wrote, the community was linked to the mine by two miles of railway and there was total of six miles of track, 75 ore cars and two 35 ton locomotives. Some 6,000 tons of ore was moved each day. Energy was provided by a coal fired steam power plant and a hydro dam.

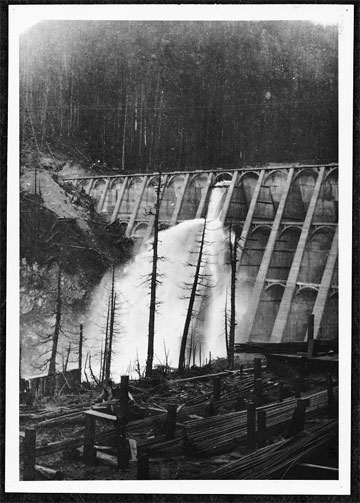

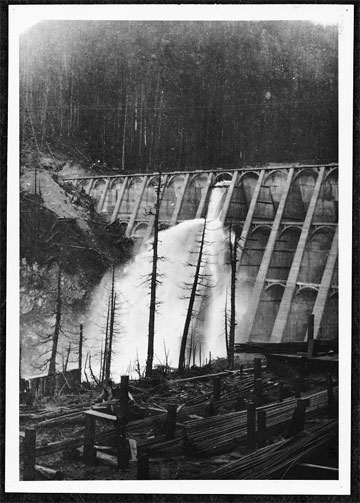

The dam for the hydro plant was itself a modern marvel. Designed by pioneering North American concrete dam builder John S. Eastwood, it was 156 feet high and for many years was tallest dam in Canada.

Photocopy of a photograph--ca. 1923--showing the Anyox Dam in British Columbia, Canada, just prior to completion of final arching. A sudden storm filled the reservoir and water began pouring over the uncompleted arch-ring; the dam was unhurt by the unexpected deluge and Eastwood used this photo as evidence of the great strength of his designs. Courtesy Mr. Charles Allan Whitney

Photo Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division - Washington, D.C.

|

The community had more than two miles of gravel roads and the wharf could accommodate three to four steamships or ore carriers at the same time. The community also had what Loudon referred to as the “westernmost golf course in Canada.” It was built on the mine tailings.

Loudon also wrote about the amenities of the community including an 18 bed hospital and a 45 room hotel, with a telephone in each room and a 60 foot long bar served by bartenders from “Italy, France, Wales, Sweden, Germany, the United States, Denmark, Norway and Russia.”

“It would become so crowded that on Saturday nights and pay nights the bartenders would permit only 120 persons in at any one time,” Louden wrote. “After an hour they would close the bar and, joining arms, force the reluctant tipplers out the door to make room for the next sitting.”

Loudon also recalled hours spent in an ice cream café and the local three-room library which had grown up’s and children’s rooms plus a reading room “where, it seemed, was displayed every newspaper and magazine ever published.”

Quarters for the mine workers and their families were better than in many communities, Loudon wrote. Many lived in single family houses.

“Every home in Anyox had electric lights, just as we all had hot and cold running water and flush toilets – which many Canadians in larger and more favoured communities could not claim in the 1920s,” he wrote.

But there was a dark side to the idyllic life, according to Loudon.

One of the more controversial aspects of the mine and smelter was gas that was emitted during smelting. Loudon says that is caused “acid rain” that stripped the neighboring hillsides of trees and vegetation and that dead trees could still be seen in the area three decades after the mine closed.

He noted that game like deer and bear were rarely seen around the community.

“Imagine children in a wilderness area who never saw game,” he wrote in 1973. “That was something else we blamed on the smelter gas. That gas incidentally was so thick that our throats were sore. Sometimes in winter it would deposit little black dots of sulpher on the surface of the snow. They would flare if you touched them with a match.”

Loudon wrote that fog and temperature inversions sometimes kept the gas at ground level leading to fits of coughing and nose bleeds.

Like most Northwest Coast towns and villages, Anyox had no road or rail connections to the outside world, it was served by steamships and other vessels.

Loudon wrote that two steamers a week connected the town with Prince Rupert and Vancouver. Those ships were generally the Canadian National steamships Prince Rupert and Prince George, although the Union Steamships liners Catala and Cardena also made regular stops.

In the summer of 1935, the end came quickly Loudon wrote, possibly hastened by a miners strike two years before.

“It had been a company town without any other jobs providing industry to speak of, so all the folks who lived there were forced to leave,” Loudon wrote in 1973. “They crated and carried with them whatever they could afford to take and scavengers came in from Vancouver to lift the rest. The company dismantled and shipped out much of the machinery from the mine.”

Left, he wrote, were the wooden houses, offices, homes, schools, hospital and stores. Most of them, used intermittently by visiting fishermen and others, lasted for another eight years.

“Then, in 1943, while the cleanup operation was in its last stages, fire ate through the scrub, the stumps and the dry muskeg of the valley floor,” Loudon wrote. “The last handful of people was forced to flee by boat and barge. The valley became a huge oven and when the fire burned itself out, little was left except concrete foundations to show that men had ever been there.”

Granby eventually sold the mining claims to Cominco, the Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company. Louden wrote in the 1970s that Cominco was still interested in the estimated 50 million pounds of copper estimated to still be in the ground, but had made little effort to reopen the mines.

Some of those “foundations” still remain, including the smelter stacks, the remains of the power plant and the 156 foot dam.

According to Canadian media reports, there remains interest in mining in the border mountains, but for now Anyox remains “the town that got lost.”

On the Web:

Columns by Dave Kiffer

Historical Feature Stories by Dave Kiffer

Dave Kiffer is a freelance

writer living in Ketchikan, Alaska.

Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us

Dave Kiffer ©2013

E-mail your news &

photos to editor@sitnews.us

Publish A Letter in SitNews Read Letters/Opinions

Contact the Editor

SitNews ©2013

Stories In The News

Ketchikan, Alaska

|

Articles &

photographs that appear in SitNews may be protected by copyright

and may not be reprinted without written permission from and

payment of any required fees to the proper sources.

|

|