by Preston MacDougall July 23, 2006

For my family, having crisscrossed the country numerous times on four wheels, the U.S. system of interstate highways is familiar territory. We have worn out many tires and several editions of the Rand McNally Road Atlas. It is all that we have needed to plan our road trips, no matter where we have gone in the US or Canada.

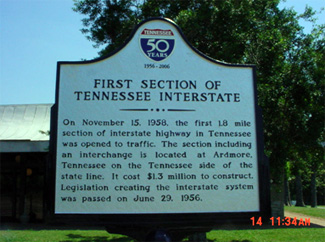

Officially named the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, this summer marks the 50th anniversary of President Eisenhower signing the legislation that led to the construction of this multi-purpose transportation matrix. At the time, Senator Al Gore Sr., from Tennessee, was chairman of the Senate Public Works subcommittee on roads, which you will learn if you enter Tennessee from Alabama along I-65. This southernmost section of I-65 crosses Tennessee the short way (for the long, long way, take I-40). This 1.8 mile stretch of I-65 was the first segment of the system to open in Tennessee, on November 15, 1958, costing less than $1 million per mile. When my family and I need a little R&R, and the white sands of Gulf Shores, Alabama, are calling, we are soon rolling across that same patch of pavement. At such times, it seems like the world has shrunk, and it's a good feeling. At other times, however, the world shrinks in an uncomfortable way. Like when CNN brings live images of someone's bombed-out living room, half-way across the world, into our relatively tidy living room. Reminiscent of Alice, in Lewis Carroll's "Adventures in Wonderland", who made herself small with the DRINK ME potion, then large with the EAT ME cake, I get yet another feeling when I read about new laboratory methods to visualize, manipulate, and chemically tailor materials at the nano-scale. For instance, research by Harvard chemist George Whitesides and his coworkers is creating technology to essentially direct the traffic of biologically active molecules to components in selected parts of a single, living cell. For this, and many other achievements, Dr. Whitesides has just been named the 2007 Priestley Medalist - the highest praise from the American Chemical Society. By controlling the flow rate and merging point of multiple, smoothly flowing, very narrow streams of solutions - each containing molecules that "tag" and relay information to and from different target molecules in the cell - they are able to send different chemical signals to the components (or organelles) in a cell. In one nifty experiment, they demonstrate the ability to get the nucleus and mitochondria (which are the energy-producing components of our cells) to "shift to the left", while the rest of the cell remains unchanged. In case you are wondering how these cellular components managed to "change lanes" when the signal came, get ready for your world to explode in size as you feel an incredible shrinking sensation - without the DRINK ME potion. After the interstate system was built, biochemists and cell biologists discovered that there was already a molecular intracellular matrix that has many functions, including connecting the various components of a single cell to one another, enabling the cell itself to change shape, and transporting chemical substances within the cell. Instead of asphalt or concrete, these molecular roadways are made out of protein. There are two types of "intracells": microfilaments and microtubules. Microfilaments do the heavy-lifting and shape-changing. They are made primarily out of the protein actin, which is found in all cells, but is particularly abundant in muscle cells. Microtubules are hollow structures that are about 25 nanometers in diameter, and can be over 1,000 nanometers in length. Like sections of an interstate, microtubules are all about the same width, but can be long or short. While only small portions of the interstates are tunnels, such as the notorious "big dig" in Boston, microtubules are all tunnel. They are made mostly out of small, bead-like protein molecules called tubulin. Chemical substances can hitch a ride on top of a microtubule as it grows, or smaller molecules can be shuttled back and forth within an intact tube. Most amazingly, in response to factors that the cell can receive, or generate by itself, microfilaments and microtubules can self-assemble and disassemble in a matter of minutes. Currently, it is estimated that the interstate system is used daily by an average of 60,000 people for every mile of highway. So, if you ever find yourself in a construction zone, and it seems as though all 60,000 are on your mile at the same time, just remember, it's always orange barrel season inside you.

On the Web:

Publish A Letter on SitNews Read Letters/Opinions Submit A Letter to the Editor

|

||