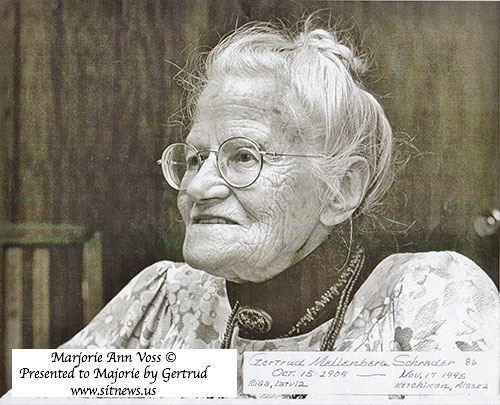

Historical Feature The Amazing, Colorful and Controversial Life of Gertrud Mellenberg SchraderBy LOUISE BRINCK HARRINGTON

November 02, 2018

Born in 1909 in Riga, Latvia (then part of Czarist Russia), she survived not only the Russian Revolution, but also World War II in Eastern Europe. Her father, Leo Mellenberg, a member of the White Russian Army, died during the revolution in a Communist prison in Riga. Her mother, Alma Mellenberg, then took Gertrud and her two brothers and escaped to Manchuria. Alma Mellenberg found work in Manchuria as a chambermaid and later at an import-export business.

When World War II broke out, Gertrud was on vacation in Germany visiting her grandmother and some friends. The Nazis arrested her, declaring her “a displaced person” (she’d been born in Russia and currently was a resident of Manchuria) and threw her in jail. Being a fearless and headstrong person, however, she talked her way out of prison by convincing the Nazis she was needed as a teacher in occupied Poland. But after a short time in Poland, she realized that the Nazis were arresting Jews and sending them to concentration camps. She watched as a German soldier grabbed a bundle of rags from the arms of a Jewish woman and threw it onto a flatbed truck. The bundle of rags began to cry. It was a baby. “I saw an SS [Germany’s elite military unit] man standing on the street, filming that incident,” Gertrud told the Ketchikan Daily News years later. “I told the SS man that it was tactless to be filming that. And he said, ‘No! Do not say that. This will be an historic document!’” When hired as a teacher in Nazi-occupied Poland, Gertrud had taken an oath to not oppose the Nazis. But now, witnessing such Nazi brutality, she wanted out of Poland—and she wanted out now. She resigned her teaching position, biked and hitch-hiked to Prague, Czechoslovakia, where she signed up for nursing courses at a university. That’s where she was in 1945 when the war finally ended. Now, her goal was to find a way out of war-torn Europe and a new life for herself, preferably in the United States. By 1956, Gertrud was working as a lab technician at a hospital in South Dakota. She decided that what she really wanted was to spend the rest of her days living in a small town on the west coast. She found three job openings available in her field—all in Alaska, at hospitals in Nome, Fairbanks and Ketchikan—and chose the one in Ketchikan, she said later, because the position at the Ketchikan General Hospital included a place to live and hot meals while on duty. Ketchikan “I was terribly disappointed in Ketchikan at first,” Gertrud later wrote in a paper for a community college course. “My first three weeks here in June, 1956, were wet and gray with uninterrupted rain. I would have left right then if I hadn’t been so stingy…I spent a lot of money to ship all of my earthly possessions here.” Five months later, however, she changed her mind, deciding that Ketchikan wasn’t so bad and buying a log cabin at Mountain Point, six-and-a-half miles from town. “It was the air,” she wrote in her paper, “the fresh, clean, windy, cool, invigorating Ketchikan air that did it!” She added that, while on her daily bicycle rides to work at the hospital, she “breathed deeply the fresh, moist air that the southeasterly wind carried from the ocean, through the channels and over the wooded islands to Ketchikan.”

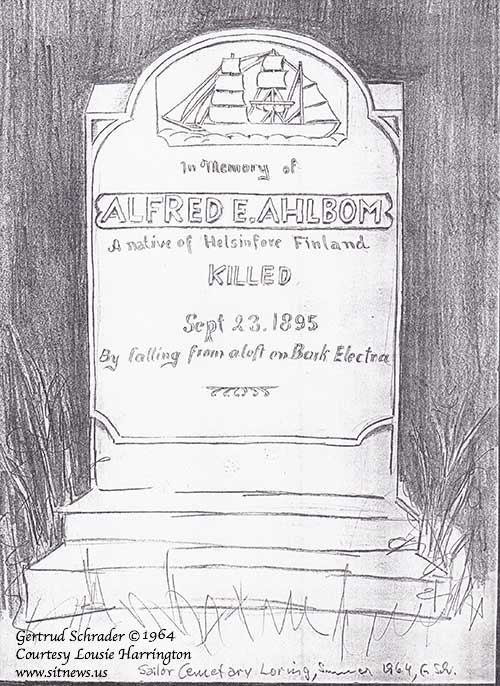

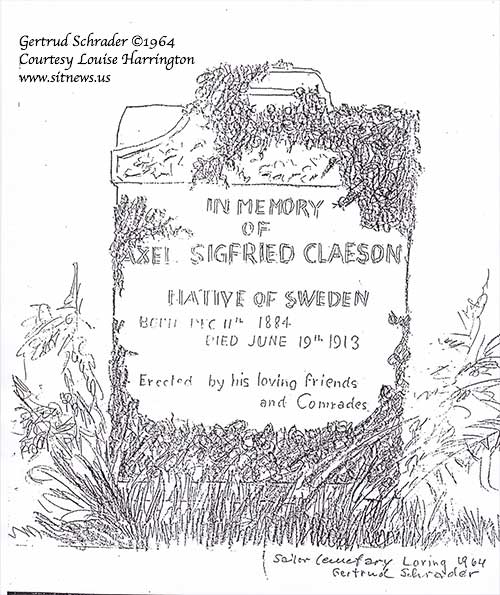

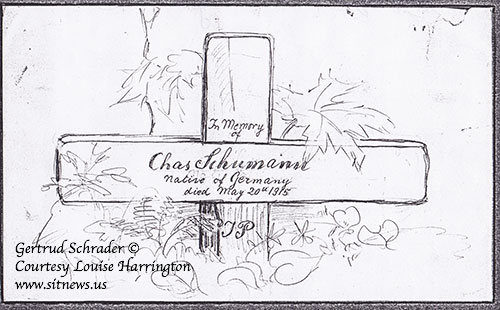

Soon after arriving in Ketchikan, she met Christian Schrader, a Danish immigrant who worked as a machinist at the Ketchikan Spruce Mill. In 1959, when both she and Chris were nearly 50 years old, they married. Neither one had been married before. A U.S. Navy veteran and born seafarer, Chris was usually seen wearing a pea coat and black woolen cap, with a duffel slung over his shoulder. He loved to sail and owned a boat that he moored at Thomas Basin. He and Gertrud spent days and weeks aboard the boat, traveling and exploring the islands of Southeast Alaska. “Oh gorgeous teeming country, full of life!” Gertrud wrote of their travels. Although she saw beauty everywhere, she did not use a camera to capture it; instead she used her sketching pad and pen to draw islands, bays, forests, everything! At the abandoned cannery town of Loring, she and Chris visited the old Sailors’ Graveyard, where she took rubbings of the ancient crumbling tombstones. She later enhanced the rubbings with pen and ink, creating beautiful black-and-white drawings—and preserving the memory of the long-dead sailors in the process. (See pictures.)

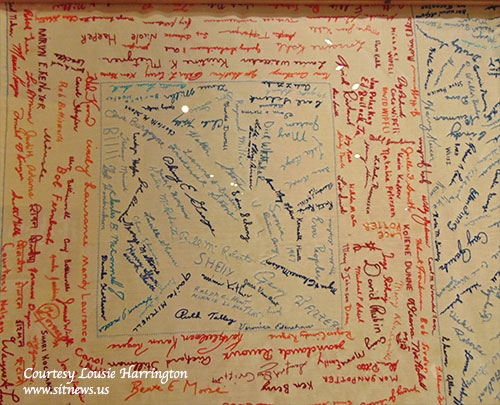

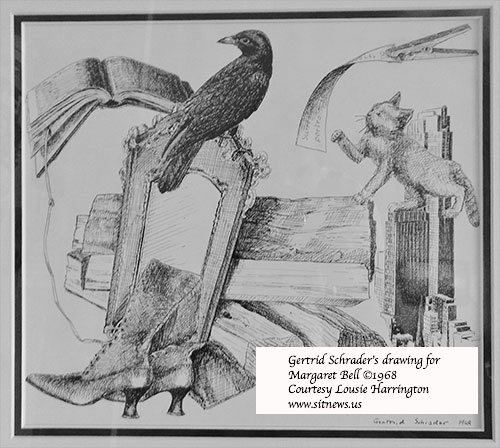

When hiking along the Naha River and the Bell Island trails, she sketched hundreds of birds. Of all living creatures, her favorite was the raven and she turned out many sketches of “Raven, that great bird of the know-how,” as she described him to a friend. Tradition! At Christmas time, in the old-fashioned German tradition, Gertrud decorated her log home with a live spruce tree, trimmed with hand-made ornaments and actual burning white candles. Each evening during the twelve days of Christmas, she invited guests to dinner, serving eastern-European dishes of red cabbage, potato dumplings, sauerkraut and sausage, topped off with almond-filled stollen, hot cocoa and schnapps. Always, a white linen tablecloth covered her square wooden table. As guests arrived, she’d ask each one to sign the linen. Then, using brightly-colored threads and yarns, she’d embroider each signature. A picture of one of her meticulously embroidered tablecloths now hangs at the Tongass Historical Museum. (See picture.)

For the children of doctors and nurses at the hospital, she hosted Christmas “gingerbread-house” parties. When her young guests arrived, they found pans of fresh gingerbread, bowls of thick frosting, red licorice, gum drops and candy canes, and boxes of toothpicks for putting together the finished works-of-art. Gertrud, of course, would instruct as to proper house-building procedure. Over the years the gingerbread houses and holiday parties became a Ketchikan tradition. All who knew of them awaited them with anticipation; all who’d heard of them yearned for an invitation. Cozy log cabin, big beautiful tree, lots of treats, lots of playmates—what could be better? Many former party goers (including me) remember them to this day. Then there were the egg-decorating parties at Easter time, when Gertrud would invite all the neighborhood kids, teach them how to color the eggs—using onion skins for dye and wax for fancy designs—and how to weave Easter baskets. Later she’d organize and direct egg-rolling contests and games in the back yard. During the month of May she scheduled Maypole dances, again inviting neighborhood kids and their friends. While teaching them how to dance around the pole, twisting bright ribbons this way and that, she’d insist they follow proper dance technique. “She’d holler at us to go over and under with the ribbons to make a braid,” remembered one former neighbor. “Didn’t get invited back to do that more than once.” To accompany the dances, Gertrud played lively folk music on her accordion. Faults and Eccentricities Not everyone appreciated Gertrud, however. At times she could be outspoken, headstrong, bossy, disrespectful, and offensive. When a state trooper stopped her for driving too slowly and holding up traffic on South Tongass Highway, she reportedly informed him: “I’m an old woman. This is an old car. We’re doing the best we can!” Knowing Gertrud and not wanting a fight, the trooper waved her on.

If she glimpsed pretty flowers growing along the roadside she’d pull over and pick them, giving not a damn if they were growing wild or in someone else’s carefully-cultivated garden. “She picked the flowers from the front bank of our house at Mountain Point,” remembered former resident Heather Robertson. “When I asked her not to, she said that I had a lot of them and she was picking them for the museum. Thought the tourists would like them!” “Once she was walking by our place on South Tongass,” wrote Patricia (Moran) Johnson in a Facebook post. “She walked in the yard and started picking my mother’s flowers out of the garden. My mother was not happy.” When she could no longer drive and needed a ride, she’d stand in the middle of the road—often wearing a long, scraggly fur coat—flag down a car, jump in and order the driver to take her wherever she wanted to go, whether the driver liked it or not. “She stopped me once and I gave her ride. I was too scared not to!” Rosemary Nelson remembered in a Facebook post. One winter, according to South Tongass resident Bill Hollywood, Gertrud even stopped the state snow plow to hitch a ride. Of course, the obedient driver did as he was told, took her to town and to her requisite destination! Then there was the time she took a group of children on a hike up Deer Mountain. When one of the children could not make it back down, the solution was simple: flag down a helicopter. Which is exactly what Gertrud did. One afternoon at the grocery store, she cornered author Margaret Bell and her husband Sam Wiks while they were shopping. Bell later wrote in her journal: “Gertrud S. was there at the store and nearly drove Sam out of his wits with her aggressive, compulsive talking.” Another time Gertrud visited Margaret Bell at her home at Loring: “Gertrud came at four in the afternoon and shouted such brutal German social ideas, I was upset and glad to see her go!” Still another visit from Gertrud prompted Bell to write: “I was writing, when Gertrud came to cook breakfast here. Surfeited with Gertrud! She rushes about and talks all the time. I suggested that they [Gertrud and friends] eat in the studio, and they did.”

Causes and Campaigns Passionate about many causes, Gertrud did not hesitate to speak her mind about them or worry about stirring up controversy. “In the U. S. you don’t have to worry about stepping on toes,” she told the Ketchikan Daily News in 1995. “You have the freedom to say what you want. You can even call your president a jackass!” During the Vietnam War, she marched on the downtown streets, brandishing anti-war signs, encouraging others to join her, and arguing with those who declined. An ardent conservationist, she believed that all living things should be protected from the Powers That Be. When the local government proposed a plan to cut down alder trees along South Tongass Highway, she campaigned against it. When the plan threatened her favorite huge cedar tree, she wrote an impassioned letter to the editor of the newspaper, pleading that the tree be saved. She even ascribed human characteristics to the tree, claiming that it had seen much during its life and was not ready to die. She loved all animals, especially ravens, which, as she wrote to a friend, were “strong, resourceful and wise creatures.” At her Mountain Point home, according to former neighbors, she adopted more than one raven, naming them all “Charlie Black.” She even trained her “pet raven” to speak and say hello to visitors. She also adopted squirrels, jays, does and fawns, and protected them all—fiercely. Litter was another source of consternation. To take a break from her work at the hospital, she’d often step outside the building’s back door, where the litter on the Edmonds Street stairs appalled her. “The children going and coming from the school [Main School] leave a constant mess of discarded wrappings and papers along the stairs, which is an ugly and unsanitary sight,” she wrote. “I will have to do something about it.” She once walked to a Garden Club meeting at a home on North Tongass Highway, collecting road garbage along the way. She filled up a big bag and upon arriving at the home unceremoniously emptied it onto an Oriental carpet—to the chagrin of the carpet owner! Gertrud’s final campaign was to raise money to build “an adequate youth hostel in Ketchikan,” according to the Ketchikan Daily News. She felt that someone should speak up for the homeless young people she met and spoke with on the streets. The final line in her 1995 obituary reads: “Friends request that memorial donations be made to Gertrud’s Youth Hostel Fund, c/o PO Box 7336, Ketchikan, Alaska.” Later Years In 1984, Chris passed away. For his burial Gertrud designed and carved a gravestone made from a piece of cedar. With a chisel she carefully etched and stained his name, date of birth and date of death on the wooden slab. After his passing, she stayed on at Mountain Point, remaining active in the community. She attended plays and performances, led mountain hikes, went backpacking on Gravina Island with friends, and even took a “walking trip” from Prince Rupert to Whitehorse with two other companions. At the Totem Heritage Center, she took a course on silver-engraving. Using her own intricate designs, she turned out some exquisite pieces of jewelry, according to her friends. “Gertrud was a talented artist, illustrator and painter,” wrote Ketchikan artist and instructor, Holly Churchill, in a Facebook post In 1994, however, failing health made it necessary for her to move to town and the Ketchikan Pioneers’ Home. She died from a stroke on November 17, 1995 and now rests at Bayview Cemetery. Her grave marker, like her husband’s, is made of cedar and engraved with her name, date of birth, and date of death. She designed the marker herself, leaving an open space for date of death to be filled in when the time came. Today the grave marker is moss-covered and returning to nature—which is just what Gertrud wanted. Her obituary in the newspaper read: “She was a treasure to this town. She loved helping people and was a friend to all. Her active mind, stimulating personality and outspoken nature became well known in Ketchikan.” A survivor of revolution and war, she lived her life according to her own rules. “She was a little strange,” wrote former neighbor, Dave Henderson, “but had a heart of gold and a very strong sense of right and wrong. And she made a point of ensuring that all of us neighborhood kids understood that!” Another neighbor, Melinda Kuharich, added: “When I’d leave for town, she’d be standing in the middle of the road, waving a big stick. I’d stop, she’d hop in and off we’d go. Never a dull moment with Gertrud as a neighbor!” Former Ketchikan resident Linda Oaksmith-Gillen neatly summed up Gertrud’s life. “What a character! She lived a colorful life for sure and never meant any harm to anyone. She was….well….she was GERTRUD!”

|

||||||||||