Chronicle, Daily News Fought The Battle Locally By DAVE KIFFER January 03, 2009

Forty-nine toasts were made, a 49 gun salute was fired and a 49-vehicle parade circled the downtown area, according to a report the next day in the Ketchikan Daily News. But Ketchikan hadn't always been so keen on the idea of self-determination for Alaska. In fact, in the early years of the decades-long battle for statehood, many local residents had been strongly opposed to the idea. The battle for statehood in Ketchikan was also the battle - to the death eventually - between Ketchikan's two newspapers, the Daily News and the Chronicle. Canned Salmon Industry Opposed Statehood From the 1920s to the early 1950s, Ketchikan was the center of the Alaska canned salmon industry and the industry - and its lobbyists - were adamantly opposed to statehood, primarily because pro-statehood forces were opposed to the fish traps that were the economic engine of the industry. Floating fish traps were placed at the mouths of creeks - and along other salmon migration paths each summer. They funneled the returning salmon into holding pens from which they were scooped or brailed into the holds of large boats and taken to the canneries.  Southeast Alaska Historic Photo Courtesy of the U.S. Fish & Wildlife - Fisheries Collection - Photographer: Archival photograph by Mr. Sean Linehan, NOS, NGS

By the 1940s, the once spectacular salmon runs were rapidly decreasing. Statehood proponents seized on the issue as a sign that federal managers were "mismanaging" the resources and that Alaskans would do better. The first person to suggest "statehood" for Alaska, was the person primarily responsible for the purchase of Alaska from Russia in the first place, US Sec. of State William Henry Seward.

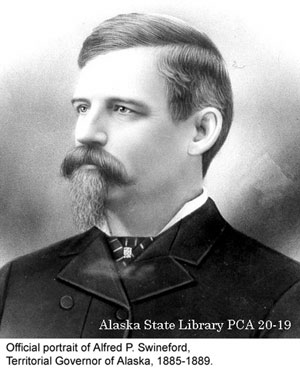

In a speech given at Sitka on August 12, 1868, Seward said " the political society to be constituted here, first as a Territory, and ultimately as a state or many states, will prove a worthy constituency of the Republic." The next person to pick up the banner of statehood was one of the first territorial governors, A.P. Swineford in Sitka in 1887. Swineford was frustrated by having to manage the vast territory with limited federal resources in those years and already understood that economic interests the large mining companies in those days were asserting control over the resources of the territory. Swineford was a miner himself and not necessarily opposed to mining, but he felt that decisions about Alaska ought to be made in Alaska not in Washington, D.C, an opinion that continues to frequently be expressed in the 49th state. Later Swineford helped found Ketchikan and started its first newspaper, the Mining Journal. He continued to opine that Alaska or at least the Southeast portion of it which then held most of the population - should get statehood status. In 1909, Judge James Wickersham began a nearly decade term as Alaska's delegate to the US Congress. After helping push through the Organic Act of 1912 that formally designated Alaska as a territory and created a territorial legislature, he turned toward the next step - statehood. But he found that some members of the Territorial Legislature were not convinced that "more government" was a better thing. Many of the legislators repeated the common refrain that Alaska was too small and too isolated and had too little money to successfully govern itself without significant federal help. Ingersoll Pushed to Split Up State One of the biggest critics was territorial Sen. Charles Ingersoll of Ketchikan. Wickersham accused Ingersoll of trying to subvert the Alaskan legislative efforts in order to benefit the canned salmon industry. In 1916, Wickersham introduced the first statehood bill in Congress. In the face of strong opposition from fishing and mining industry lobbyists, it went nowhere. Back in Alaska, Ingersoll was at the center of a debate to split Alaska into three separate territories with Southeast as the most likely to eventually achieve statehood. Wickersham considered the splitting up effort an attempt to push statehood even farther onto the federal government's back burner. The only clear result of the Alaskan statehood debate was that by the mid 1920s, Congress had passed laws that in effect strengthened the existing monopolies in the Alaskan fishing and maritime industries. In the words of several national magazine and newspaper stories at the time, Alaska was little more than "colony" of the Lower 48. At the head of the anti statehood efforts was the lobbyist for the Alaska Packers Association, W.C. Arnold.

"The fishing and cannery industries employed W.C. Arnold, a man so powerful that he was called 'Judge Arnold,' " Alaskan historian Claus Kaske told the San Francisco Chronicle in September of 2008. "Arnold was a skookum lobbyist, and he told Congress that business was paying the cost of running the territory." "We don't propose to pick up the check for statehood," the normally "behind the scenes" Arnold told the New York Times in 1943. Like all great lobbyists, Arnold and other representatives of the Alaska Packers Association used a bit of "misdirection." They never came out and directly opposed statehood, but they painted a picture of economic chaos and other hardships that would happen in the territory if control shifted to a state government that "couldn't support itself." Early On, Residents 50-50 On Statehood Although there were no scientific polls done in those days, the public discourse in the newspapers of the state showed that residents were generally split 50-50 on the idea of Alaskan statehood. But as time passed, that began to shift, even in Ketchikan. World War II had seen the state's population nearly double. Most of the increase was in military personnel, but a large percent was also in the service industries needed to support the build up. The population increase was also responsible for helping shift the population and political centers of the state northward, from Southeast in into what is now called the "Railbelt" of Anchorage and Fairbanks. Although the mining industry was prominent in the Railbelt, the salmon canning industry - which had carried most of the lobbying weight in the anti-statehood movement - was not. The salmon industry was also in a period of severe "retrenchment" due to the success of the fish traps. Salmon runs had dropped to a fraction of their levels in the 1920s and 1930s. In 1946, the Territorial Legislature - which was now made up of an nearly equal number of Railbelt and Southeast legislators approved a statewide referendum to determine the public support for statehood. Alaska-wide the margin of support for statehood was better than 2-1, but Ketchikan had a narrower margin. Just over 700 residents voted in favor of statehood while nearly 550 opposed it. But the fact that the center of the canned salmon industry was now - barely - in the pro-statehood camp was significant. Chronicle and Daily News Battled Over Statehood During the 1940s and 1950s, the battle for Alaskan statehood played out in the pages of Ketchikan's two daily newspapers, the Chronicle, which had been the dominant voice in Ketchikan since 1919 and the Daily News which started as a weekly newspaper in the 1930s and became a daily in 1945. The Chronicle had been founded by Klondike stampede journalist Bernard Stone, who had also founded the Anchorage Times. When Stone and his partner Ed Morrissey founded the Chronicle in May of 1919, Ketchikan was poised to be the dominant community in Alaska -a position it held until the early 1930s. While the rest of the territory was in a post World War I economic slump, Ketchikan was enjoying rapid growth in the canned salmon industry and had also become the largest port in the Alaska. Initially, the Chronicle competed with the Ketchikan Times, according to Lew Williams Jr's comprehensive 2006 history of Alaskan newspapers, "Bent Pins to Chains." Although both newspapers had strong advertising and circulation support, the Chronicle also benefited by being favored by the salmon canning industry and also received a lucrative contract to print canned salmon labels. The two newspapers also took differing views on Ketchikan burgeoning reputation as a "vice ridden" community, as prostitution and rum-running from Canada both increased. The Times took a more traditional Alaskan position of "live and let live," but the Chronicle went as far as encouraging local residents to boycott businesses that were involved in the bootlegging operations. The Chronicle won the battle for public support and the Times went out of business in 1920. The Chronicle then took the leadership role in the community that it would hold for more than two decades, despite sporadic competition - most notably from a Ketchikan Daily News that was founded in the early1920s and has no connection with the current Daily News. In 1923, the idea of splitting of Alaska up once again reared its head. The Alaska Railroad had just been completed between Seward and Fairbanks and there was strong support in Northern and Western Alaska for moving the territorial capital from Juneau to Seward. "An idea originated in 1923 to have Southeast residents vote on whether they wished to split off from the rest of the territory," Williams wrote in "Bent Pins to Chains," adding that both the Chronicle and the early Daily News supported the idea in news stories and editorials. On November 7, 1923 residents of Southeast voted by a wide margin to "split off" from the rest of the state, and residents of Cordova also voted to join the Southeast "territory." In Ketchikan, the vote was 441 to 39 in favor of the split. Census figures show that Ketchikan had a population of 2,300 at the time. Although representatives from Alaska took the proposal to Washington D.C. it went nowhere. Not surprisingly, representatives of the Alaska Packers Association convinced Congress that Alaskan self government, even only for Southeast, was a bad idea.

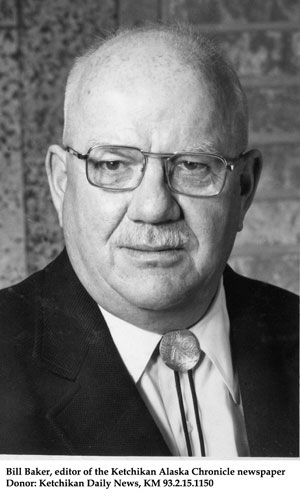

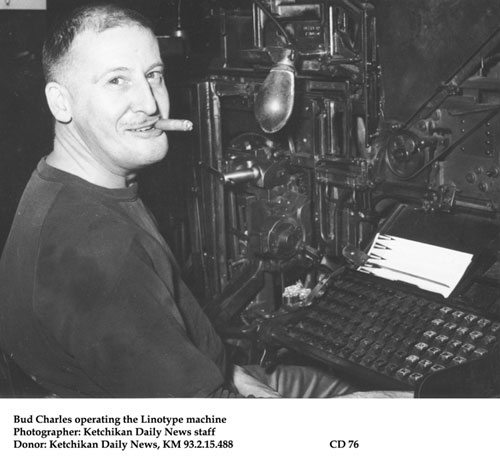

By 1924, the first Ketchikan Daily News had gone under, but that year a veteran Alaskan newspaperman named Sid Charles arrived in Ketchikan. He would eventually resurrect the Daily News and - even later - win a longtime newspaper battle with the Chronicle. Charles had been an Alaskan newspaperman since 1904, publishing or editing papers in Anchorage, Cordova, Juneau, Chitina, Skagway, Petersburg and Sitka. He went to work for the Ketchikan Chronicle in 1924, but left the paper after being seriously injured in a boat explosion at City Float in 1926. He returned to work at the paper, but then was fired in 1934 when new owners took over the Chronicle and decided that Charles - at 63 - was too old. At first, things went well for the Chronicle. It expanded to seven days a week for several years and had its first Alaskan born editor, Roy Anderson, who had been born in Ketchikan in 1905. Among the new co-owners was W.C. Arnold. Charles Edits Weekly Fishing News In 1934, the Alaska Trollers Marketing Association funded the founding of weekly Alaska Fishing News. Sid Charles was its one person editorial staff. "The salmon trollers organized a cooperative in the summer of 1934 to bargain for higher prices for the catches," Williams wrote. "They wanted their own newspaper to tell their side of the price dispute. The Chronicle invariably took the processor's side." Ironically, although the battle lines were drawn, it would take nearly a decade for war to break out and the two newspapers wind up battling from the opposite sides they began on. By December of 1934, Charles was the sole owner of the Fishing News and was publishing twice a week. In 1939, it went to three days a week. "Alaska's First City enjoyed relative harmony in its local press between 1935 and 1944, especially in the years that hometown boy Roy Anderson owned the Chronicle and Sid Charles the Alaska Fishing News." Williams wrote. "Both shared mutual respect and appreciation for the canning industry and its roll in the town's economy." Both also distrusted the long-time territorial Governor Ernest Gruening, a major proponent of statehood. But things changed dramatically in 1944, when Oregon newspaperman Bill Baker purchased the Chronicle. Baker was a vociferous supporter of statehood and an equally strong opponent of the power of the salmon industry. The "friendly competition" between the Chronicle and the Fishing News was over.

In 1945, the Fishing New began publishing daily. On August 1, 1947, it changed its name to the Ketchikan Daily News. "The News and Chronicle took opposing positions on the three major issues of the day - Gruening, fish traps and statehood," Williams wrote. In fact, Charles' dislike of Gov. Gruening was so strong that he derided Gruening's attempts to encourage a pulp mill to be based near Ketchikan as "fantasy." Charles also accused Baker of "lying" when the Chronicle reported that the pulp mill was a certainty. Both newspapers ratcheted up the heat in numerous editorials, the Chronicle supporting statehood as "inevitable" while the Daily News opining it as "unaffordable." "The Comical Versus The Fish Wrapper" Charles often derided the Chronicle in print as the "Daily Comical" while Baker used the Daily News history against it as "the Daily Fish Wrapper." In the mid 1950s, the canned salmon industry and several major business - including the Alaska Steamship Company - pulled their ads from the Chronicle and doubled their ad space in the Daily News. In his book, Williams downplays the effect that the loss of ad revenue had on the Chronicle, writing that Baker was more hamstrung by a series of libel suits that he allowed to distract him from running the newspaper. Former State Legislator Oral Freeman - a statehood proponent disagreed. "When the ads were pulled from the Chronicle, it was the end," Freeman said in a radio interview on KRBD in the mid 1990s. "The industry convinced most of the big advertisers to jump ship even though most of the people in town still supported the Chronicle." In 1957, the Chronicle shut down , although Baker tried to run it as a weekly off and on for several years. He also unsuccessfully sued the Daily News for libel and restraint of trade. Baker won on the libel charges but not on the other ones. Eventually he gave up on the local newspaper business and turned his attention to the radio and cable television news. His televised show, "Totem Land Topics" was broadcast in the 1960s and 1970s. He died in Ketchikan in 1988, outliving Sid Charles by nearly 30 years.  Bud Charles Photo courtesy Ketchikan Museums

Alaska Was 'Blue' And Hawaii Was 'Red' Efforts to lobby for statehood continued at the federal level in the 1950s. Surprisingly enough - in this era when Alaska is firmly a politically conservative "red" state - one of the main arguments against Alaska statehood during the Eisenhower era was that Alaska was perceived as a predominantly Democratic state. It wasn't until Hawaii's statehood efforts were bundled with Alaska's - in the 1950s, Hawaii was a solidly Republican state - that enough political power was mustered to gain statehood, despite the continuing arguments that Alaska was too remote and too poor to support itself as a state (it would be a decade before the first large oil strikes were made). After the federal government decided on Alaska statehood in the summer of 1958, one last hurdle remained. The citizens of the proposed state faced one last vote - in October of 1958 - on whether to become a state or remain a territory. Although the salmon processing industry made a few half-hearted attempts to lobby voters to turn down the plan, the tide had already turned. Territory wide the pro statehood vote was 26,678 to 4,777. Even in Ketchikan, it was a landslide, 2,324 yes votes and only 512 opposed. On January 3, 1959, Ketchikan became the "First City" in the 49th State in the Union.

On the Web:

Dave Kiffer is a freelance writer living in Ketchikan, Alaska. To republish this article, the author requires a publication fee. Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us

|

|||||