Canoe Accident Led To The Founding of Saxman Tribes had hoped to locate new village on Annette Island By DAVE KIFFER November 26, 2009

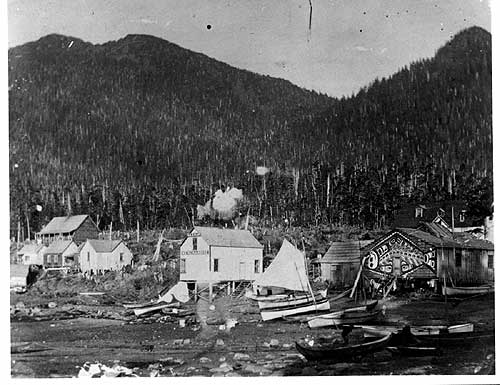

The canoe accident was also, somewhat surprisingly, worthy of a story in the New York Times. The modern day community of Saxman is the result of the combination of two Native villages. At the time of its founding, 1894, residents of Cape Fox and Tongass villages chose to leave their ancestral homes and move into a newly created village just south of the tiny village of Ketchikan in order to have access to a government school and to missionaries.  Donor: Arthur Bryant, Tongass Historical Society Photograph courtesy Ketchikan Museums Both the Cape Fox and Tongass villages had existed for several centuries in the lower portion of the Alaskan panhandle. But life in those villages began to change when contact was made with the traders and explorers in the 1800s. Cape Fox village was located about four miles south of Boca de Quadra, approximately 40 miles south of Ketchikan. A US census in 1880 determined that 100 people were living there. The village of Tongass was located on a small island, adjacent to the eventual United States/Canadian border at Portland Canal. In 1868, the United States stationed a small military garrison at Fort Tongass to act as the customs port for the newly purchased territory. The base was abandoned in 1870 but the customs official stayed on in the community. In 1879, US officials estimated the Tongass village population at 700. Tribes Asked For School According the August 8, 1885 edition of the "Alaskan" newspaper in Sitka, Dr. Sheldon Jackson, the federal agent for education in Alaska, had met with representatives of the Tongass and Cape Fox tribes to hear their concerns about the need for a school and their stories of the havoc that alcohol supplied by the traders had done to their traditional way of life. Tillie Paul translated for the tribal leaders and then wrote minutes of the meeting for the American authorities. "A long time ago when I was a little boy a ship come into the harbor at Tongass and I ran down to the beach to see it," John Kontich of the Tongass Tribe said. "Its coming made me very happy. As a boy I ran to meet the ship, so now as a man with joy I receive your promise of a school." Billy Williams agreed. "Give us a good anchor so that we will not drift away" he said. "We know that we do not live right, but when the teacher come we will do better." Kyan (only name recorded) said that a new school could counteract the bad that was coming from the "whisky traders." "I have many children and I want them to go to school and learn," he said. William Edmunds told Dr. Jackson that "drinking and fighting" had gotten so bad that he had moved from Tongass to Port Simpson, B.C. in 1882. "We are hungry for the gospel and now that you have come, we are looking for your help," he added. Thomas Johnson said that he had also spent time in Port Simpson, which was just across the border, some 15 miles from Tongass village. "Some have built houses here (Tongass) but I waited to see where the school house was to be," he said. "I want to live by the school. I am hungry for the gospel. I am starving for it. I am willing to do what you say to us. We are your children. Direct us." John MacKay agreed. "I want a home by the school where I can live right," he said. "I am willing to give up my home (at Cape Fox) and build again where I can have a school for my children." Both George Paul and George Johnson told Dr. Jackson that the Natives needed a combined village for both tribes that was separate from the temptations of the existing communities, so that the Natives themselves could "do better." But clearly the strongest testimony at the meeting came from the two head chiefs, Kah Shakes of Cape Fox and Ebbitts of Tongass. "I have six children and I will build near the school house," Kah Shakes said. "You have sowed good seeds in the heart of the people, all over Alaska," Ebbitts said. "Now among us, too. Kah Shakes and I have selected a good place for the new village. We wish you to go look at it." The place the Chiefs had selected was the site of a former Tlingit village sometimes called Old Tongass, also referred to as Taquan, at Port Chester on Annette Island. At that point in history, Father William Duncan and his Tshimpshian villagers were still in northern British Columbia at a village called Metlakatla located south of Port Simpson and just north of what would eventually become Prince Rupert. Within two years, they would move to Alaska and found New Metlakatla at the Port Chester on Annette Island favored by Kah Shakes and Ebbitts. Jackson Chose Loring Later that Fall, Jackson decided against founding a brand new community to house the members of the Tongass and Cape Fox tribes. He chose, instead. to build the school and locate a missionary in Loring which was referred to by the Natives with its traditional name of Naha. Loring, some 20 miles north of what would eventually become Ketchikan, was the largest community south of Wrangell at the time and had a large cannery. The Natives were not happy with the decision to move the school to "Naha." On January 24, 1886, Louis Paul of Tongass village wrote a letter to Sheldon Jackson. "The people would be discourage to hear of the building at Naha it would be useless for me to try them to move because I know just as plain what they want, what can I do, at Naha there will be a school house and teachers and nobody to teach," Paul wrote. "Some of the people have already gone to Port Chester to lay the foundation and I don't know how I will tell them of the building at Naha they will laugh at me. We hope and pray that the Board would change they mind about the building at Naha. If you have building at Port Chester we will have Hydah, Cape Fox and Tongass together." But Jackson went ahead with his plans to consolidate the Native education at Loring, primarily because he had already made arrangements with Loring businessman Max Pracht, superintendent of the Alaska Salmon Packing and Fur Company, for a building that would serve as both school and living quarters for a teacher until a separate school building/residence could be built. In the Fall of 1886, a school was established at Loring and Pennsylvanian educator and missionary Samuel A. Saxman and his wife Elizabeth moved there. Saxman and his wife had been waiting for several months to get the "commission" to move to Alaska. Dr. Jackson had begun corresponding with them in the fall of 1885 and they made arrangements to leave their post in Pennsylvania. But then Congress delayed on funding the "mission" and the Saxmans were left hanging in the summer of 1886. As late as July 30, 1886, Saxman despaired in a letter to Dr. Jackson. "I had presumed to hear form you this week; but not hearing I think best to write. I presume it has gone against us and you hesitate to break the news; but care not for us, I pity the children whom we might have helped and led to Jesus," Saxman wrote. "If Congress failed us and you are and will remain like minded to us we can bide our time for another year or two and in the mean time let us write for papers to friends and stir up public sentiments in favor of Alaska until the appropriation or other means opens up the way for us. Where there is a will there is a way." But Congress did finally come through and on August 10th, the Saxmans received the news they were hoping for and quickly wired Dr. Jackson.. "Commission to Loring received. Accepted. Go on first steamer." On September 3, they left Port Townsend on the coastal steamer Ancon. They arrived at Loring on Sept. 10. Initially there were few students, but Saxman wrote to John Eaton on Sept. 13 that he had been assured by Pracht and local Native leaders that Native families would eventually move to Loring to attend the school. Unfortunately, by November, it was clear that Paul was right. There was indeed "nobody to teach" in Loring because the Natives refused to move. Jackson gave the Saxmans permission to head south to Fort Tongass for the winter and attempt to hold classes for the Native children there. Jackson accompanied the Saxmans to Tongass on the motor boat Leo and then continued south to Seattle. They arrived at Tongass on December 1. The missionary teachers' move took W.H. Bond, the deputy collector of customs and local American authority there, by surprise. "I did not know they were coming until they landed here," Bond related, later, in a letter to the "Alaskan" newspaper in Sitka. "I gave them a large front room at my quarters and did what I could to make them comfortable, and in a day or two they had themselves fixed for the winter." Saxman, Paul Left to View Annette Site Almost immediately, Saxman agreed with the villagers and saw the need for a new village, one that would be free of the bad influences of the existing communities. "There has been (as I suppose you have heard) a desire to establish a mission at Old Tongass by those connected with missionary affairs," Bond wrote the Alaskan on January 29, 1887, more than a month after the tragic canoe trip. "Prof. Saxman was expected to visit the place when it was practicable so to do and to report as to its advantages." On December 13th, Saxman, Native teacher Louis Paul, and another Indian named Wah Koo Se, according to Bond, left Tongass to head north in what Bond considered a large, well-ribbed and strong canoe. He noted that Louis Paul was considered "one of the best canoe men that we had." "That part was all right," Bond wrote the Alaskan. "(But) I felt very uneasy about their going at this season of the year particularly until after the cold snap which always sets in about Christmas and so I told them." Bond said that Paul told him he was wasn't worried about cold snap because he planned to return to Tongass before it occurred. "I reasoned that it might set in a week sooner or so and prevent their coming home for a month; that they might get out of provisions and suffer terribly from the cold and privation," Bond wrote later. Bond said he was also concerned because he felt that Saxman was not yet a man of the country. "Prof. Saxman was a rather delicate man, never had anything to do with boating or exposing himself about the water," Bond wrote. "They started, however, feeling anxious to act with promptness in reporting as to the feasibility of starting a mission at that place (Port Chester)." The plan was for the men to return within five or six days, depending on the weather. Bond said that initially the weather was rough beginning on Dec. 13, but after three or four days the weather calmed down and actually turned fairly nice. But there was no sign of the canoe or the men. "We began to be restless and uneasy, and the Indians of the village began to talk considerably among themselves about the probability of their being drowned," Bond wrote, adding that there was also talk about leaving the village to find them. Then the weather changed. "The north wind, and very cold weather accompanying it, set in at this time with a vengeance. It blew harder than I have ever known it." It was now Christmas. "Poor Mrs., Saxman suffered the most intense mental agony, the horrid suspense becoming unbearable,." Bond wrote. "Day after day passed, we all suffered and it was all we could do to bear them up with the idea that it was impossible to return in a such a wind and sea, that they were quartered in some (Native) houses on the big island (mainland) and would not suffer having plenty of ammunition." Captain Orr Searched For Missing Men On December 31, 1886, the storm finally broke and Captain F.C. Orr, a trader, offered to take his boat north to look for the men. On January 1, 1887 the weather picked up again, but Orr still chose to head north. He left on a Saturday and told the villagers he would be back on Tuesday. When Tuesday passed with no sign of Capt. Orr, Bond wrote that he despaired that Orr had also come to grief. But on Jan. 6, the trader returned to the village. Unfortunately, the news regarding the Saxman canoe was not good. "He made me acquainted with the fact that all was gone and that there was no hope," Bond wrote. "They had found the canoe, the step was broken out, she was driven upon a rock and bound by a fallen tree, several cracks were visible." In addition to the canoe, Orr had found paddles, oars, rudders, empty provision boxes, sacks of flour and coffee and a mat full of blankets. But there was no sign of the three men. Two days later, 25 Natives left in three large canoes, hoping to find the men's bodies. They found additional debris and evidence that the canoe party had camped twice on 60 mile journey and that the bad weather on the third day of the canoe's trip may have broken the mast and caused the canoe to overturn. The canoe and most of the debris was found on Annette Island, not far from Port Chester, but the exact location was not recorded. Bond's Jan 29, 1887 letter to the "Alaskan" also included biographical details about Saxman and Paul. He noted that Saxman was 32 years old, had been born in Armstrong County, PA and was "a perfect gentleman, a man of fine culture and rare attainments, a very enjoyable companion" who was a member of several social and fraternal groups such as the "F&AM, IOOF, AOUW and the Secret Knights." He noted that Louis Paul was born Louis Pyreay in Nanaimo, B.C. and that his father was a Frenchman and Paul had taken the name Louis Paul because his father's name was too hard to pronounce. Paul's father was a trader who had been murdered when Paul was a young boy. His mother, a Native of the Tongass area, had brought him back to the village and then died soon after. He had attended school in Wrangell and had been married to Tillie Paul nearly five years. Times Printed Story of Lost Missionary Nearly a month later, Feb. 27, 1887, an article appeared in the New York Times under the headline "Teachers Drowned." The article was a reprint of a story three days earlier in the Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette and was based on a letter that Mrs. Saxman had written to the Superintendent Morrow of the Allegheny County School District. It generally followed the same outline of events that Bond had related to the "Alaskan," with a few obvious errors (Tongass, for example, was referred to as Longas." But it did offer more biographical material about Samuel Saxman. It noted that five years previously he had served as the Principal of Elmsworth School in Allegheny County, then was the "confidential clerk" in Superintendent Morrow's office. After that he had graduated from the Indiana State Normal School and had become principal at Corsica Academy in Westmoreland County. Then he had and his wife had left for Alaska. "In September last, Superintendent Morrow received a letter from Mr. Saxman suggesting that the school children make up boxes of cast off clothing and send them to him for missionary purposes," The Times reported. "Acting on this suggestion, the school children of the Second Ward under Profs. Daniel and Farrar and Prof. James Morrow of the Fifth Ward (all in Pittsburgh) made up four nice boxes, all valued at $100, which Superintendent Morrow shipped October last. Two of these boxes arrived in December and two in January but as Mrs. Saxman pathetically writes in her letter 'Too late, too late.'" Mrs. Saxman returned to Pennsylvania after a short stop in San Francisco, thus ending her family's brief connection to Alaska. But Louis Paul would leave a much greater legacy in Alaska. Two of his sons with Tillie Paul -William and Louis - went on to become leaders in the Alaska Native Brotherhood and major figures in the Alaska Native Civil Rights Movement. (see "William Paul Was The Father Of Native Land Claims" SITNEWS Feb. 16. 2009). With Saxman's death, efforts to create a new school for the area temporarily stalled. Tsimpshians Chose 'Old Tongass" Site Father Duncan and the Tsimpshians, who had reportedly previously scouted Annette Island during their decades long dispute with the Canadian and Anglican authorities, moved into the vacuum by relocating to Port Chester and founding New Metlakatla. It was soon the largest community in the region with more than 1,000 residents. Within 10 years the island would be granted reservation status by the United States government. One historical account, reprinted in the book "Haa Kusteeyi, Our Culture, Tlingit Life Stories," says that Father Duncan visited Tillie Paul after her husband's death and she suggested he relocate to Old Tongass. Finally seven years after Saxman's death, on July 4, 1894, the village of Saxman became a reality. According to a story in the Dec. 18, 1906 issue of the Ketchikan Mining Journal ,a conference was held between the leaders of the Cape Fox and Tongass tribes on that date. They met on a beach at the mouth of Ketchikan Creek, the same location that the community used for its baseball field in the early days. The conference was presided over by Dr. Sheldon Jackson and the goal was to see if the two tribes could agree on a new location for a joint town site and a school "Efforts had been made before 1894 to help these Natives, but owing to their separated villages the work was not successful," the Mining Journal reported. "After much discussion they concluded that a place toward the lower end of Tongass Narrows would be the one for the new town. The place was on the direct route of the steamers. It had a good beach and harbor." It was also noted that the location, some two miles south of the village of Ketchikan, was "not dense with forests and afforded good water and room for a large sized village. Also the place was a center to all the hunting and fishing grounds of the Natives." Village Named After Missionary The Mining Journal reported that the Natives chose to name the village after the teacher who had drowned 7 years previously and Jackson promised them a day school and the services of a minister if they would relocate to the new village. By the fall of 1894, some villagers had already started putting up the first houses and the school building was under construction. A sawmill was also constructed. Mr. J.W. Young was the first teacher and missionary in the new village. In 1929, the village of Saxman incorporated as second class city. Shortly thereafter totem poles were brought in from the deserted villages at Cape Fox and Tongass by the Civilian Conservation Corps and made the centerpiece of the Saxman Totem Pole Park, one of the major cultural and visitor attractions in the area. Its population is 431, according

to the 2000 US Census.

On the Web:

Dave Kiffer is a freelance writer living in Ketchikan, Alaska. To republish this article, the author requires a publication fee. Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us

|