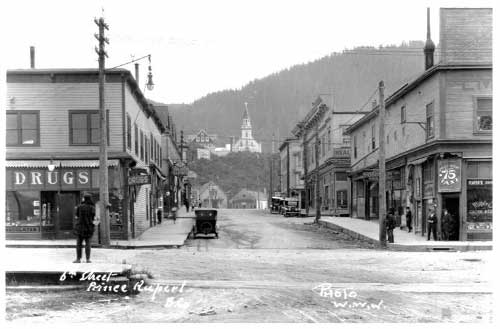

Prince Rupert: Hays' 'Orphan' Looks To The Future By DAVE KIFFER February 28, 2007

At the time of his death, Charles Hays was president of the Grand Trunk Railway. He had plans to make the tiny waterfront village at Prince Rupert into the major seaport on the west coast of North America.  Photo courtesy Prince Rupert City and Regional Archives

Hays was born in May of 1856 in Rock Island, Illinois and took early to the railroad life, first working for the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad in St. Louis, Missouri at the age of 17. Within five years he was an executive with the Missouri Pacific Railroad and by 1884 was secretary to the general manager of the Wabash, St. Louis and Pacific Railroad. Four years later, he was the general manager of the Wabash. While Hays was building his career south of the border, Canada was trying to build a country to the north. The infant Dominion was very concerned about connecting its more developed east with the resource rich and underdeveloped western prairies and Pacific coast. There was also concern that as the US developed its West Coast there would be pressure on the Canadian west to join forces with America. By 1867, the Grand Trunk Railway was one of the largest rail line systems in the world with more than 2,000 miles of tracks and dominated eastern Canada and the northeastern United States. Canadian officials approached the Grand Trunk in the early 1870s about commencing on a line to the Canadian west, but its British owners balked, saying that the west didn't have sufficient population to warrant a rail line yet. It was a decision they would regret. The Canadian government then worked with other financiers to create the Canadian Pacific line, which after several fits and starts finally completed the Canadian transcontinental line to Vancouver in 1885. By the mid 1890s, the population of western Canada was booming and the national government of Wilfred Laurier was openly encouraging more rail routes into the west. By now Grand Trunk had seen the error of its earlier ways and was looking to expand west. In 1895, it hired Hays to improve its operations and look at expansion. The Grand Trunk line eventually reached agreement with the Canadian government for a transcontinental line from Moncton, New Brunswick to Port Simpson, B.C. The government would pay 75 percent of the cost. In 1903, the Canadian parliament approved the deal. After further planning, it was decided that the line should terminate just south of Port Simpson on the British Columbia coast. The area had been populated by First Nations Tsimpshian tribes for more than 10,000 years, but white settlement in the area was limited to trading posts or small villages such as the William Duncan's original Metlakatla. Hays chose the area because

it had one of the deepest ice free natural harbor in North America.

It was also some 500 miles closer to the Orient than the ports

of Vancouver and Seattle and could offer shorter shipping A national contest was held to select the name of the new community and Eleanor Macdonald of Manitoba won $250 with "Prince Rupert" after the original Governor of the Hudson's Bay Corporation in the 1600s The beginning of Prince Rupert is easy to pinpoint. The morning of May 17. 1906, the coastal steamer Constance left the village of Metlakatla and wound its way through the Venn Passage into what was then called Tuck's Inlet. She unloaded the first working party which consisted of two carpenters on the shore of Kaien Island. "The shores were steep-to and heavily wooded and the two carpenters - Legatt and Edgecombe, with their Chinese cook - had a hard time scrambling up the rocks and getting their supplies ashore," wrote R.G. Large in his 1960 book "Prince Rupert: A Gateway to Alaska and the Pacific." "Rain fell heavily, the bush was thick and wet and the ground soggy. What a start for a city of 50,000 people." That was the eventual population Hays estimated to his financial backers. But in May of 1906, the initial population was five, after two engineers joined the original workers. The crew quickly got to work and cleared space for a tool shed and tents and immediately started construction on a wharf. There was urgency because the Grand Truck Pacific Railway was already pushing westward. Within a year, the first streets were laid out and land had already been cleared back toward what would be called Mount Hays and Mount Oldfield. By summer of 1907, there were 150 residents of the community, according to Large, mostly laborers, but also a few store owners to supply the workers. About that time a Scottish miner named John Knox moved to the new community and immediately filed some claims adjacent to the townsite. Soon his area was called Knoxville and others joined him. Knoxville would last for nearly two years before the construction of the waterfront railway yards meant it had to go. But residents of the area didn't want to leave. "War was openly declared," The Prince Rupert Empire reported in a story headline "The War in Knoxville" in May of 1909. "First shot fired (by dynamite) wrecked O'Brian's barbershop, threw mud on McKinnon's Bread and smashed many windows. A frontal attack on the enemy stronghold was planned by the Knoxvillites but failed in its initial stage." As more land was cleared, the town population first jumped to 1,500 and then 3,000 by the fall of 1909, according to the other town newspaper, the Prince Rupert Optimist, which would eventually become the town's surviving paper, the Daily News. The town continued to grow and - although it was still a company town - it was officially incorporated in May of 1910. Then two significant disasters struck the young community. First in September of 1911, the Liberal Party of Wilfred Laurier lost power after 15 years leading the Canadian government. Laurier had been a strong proponent of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway as a way to solidify Eastern Canada's hold on the western provinces at a time when there was significant agitation in the west to join with the United States. When the Conservative Party took over in 1911, it didn't pursue western "issues" as strongly as the Liberals had. A previous Conservative government had also played a significant part in establishing the Canadian Pacific line and the new government was loath to strongly support the Grand Trunk which had been sponsored by the Liberals and was perceived as the Liberals' "railroad." Then in 1912, Hays died on the Titanic after a trip to England to discuss financing for his growing western empire. "With him went all the plans for the future development of the port of Prince Rupert," Large wrote in 1960. "Strange to say, these were carried in the President's head and had never been committed to paper." This proved not to be entirely accurate in the mid 1990s, when a set of preliminary diagrams for significant local buildings done by famed architect Francis Rattenbury were found in a Victoria attic. For the time being, development of Prince Rupert continued to move ahead and the rail line arrived in Prince Rupert in 1914. But by then the Grand Trunk line was already beset by inconsistent management and was sorely missing Hays' vision for its success. By 1920, it had been absorbed into a new railway, the Canadian National, which the government had created out of the failures of several smaller lines, including the Grand Trunk. The Grand Trunk name would live on in some remaining branch lines including the Grand Trunk Western in Michigan, which would eventually inspire the name of the American rock band, Grand Funk Railroad, according to the band's website. Since the Canadian Pacific had reached Vancouver more than two decades ahead of the Grand Trunk it was better established. Despite Hays' contention that Prince Rupert was 500 miles closer to Asia, the Vancouver-Prince Rupert port competition would always favor the larger city. Even if the idea of Prince Rupert as major port was not taking off, residents pushed ahead with other industries. World War I brought a need for spruce for airplanes and even large quantities of sphagnum moss - which was used to treat war wounds. A major drydock and shipyard was also built in Prince Rupert in 1918. By then, the population had climbed to nearly 5,000, according to Large. The fisheries industry was also in a boom period after World War I and that helped the economy grow. The first grain elevators were built in the area in 1925 and shipments of grain from the central provinces began making their way from the port to Asia. Unfortunately, the shipments stopped almost completely during the Depression in the 1930s. About the only growth industry in Prince Rupert from the late 1920s to the mid 1930s was bootlegging, which carried on a steady business with the "dry" communities to the north in Alaska. Like its American neighbors, the economy of Prince Rupert was shaken from its doldrums by World War II. The shipyard, which was built in 1925, was the largest one in British Columbia and immediately began building 10,000 ton steel freighters for the war effort. By 1945, the shipyard had turned out four minesweepers and fifteen freighters. "For five years, the economy was run on a wartime basis and ports, railways and shipyards became key components of the nation's war effort," W.M.B. Hick wrote in "Hay's Orphan: The Story of the Port of Prince Rupert" in 2003. "Prince Rupert, the focus of great enthusiasm in the first decade of the century, then dormant and almost abandoned for the next three decades, at last achieved recognition for the role it could play as land/sea interface in the struggle to contain and defeat Japanese Pacific aggression." By the spring of 1942, the US military had chosen Prince Rupert at the railhead from the Alaska and it played a key role in the Aleutian Islands campaign. Approximately $16 million was spent to build a barracks for 3,500 mostly American soldiers and a highway from along the Skeena River from Prince Rupert to Terrace was also begun. Activity peaked in 1943 as Prince Rupert's population boomed from 6,500 to 23,000. When the Japanese were driven from Attu and Kiska later that year, activity in Rupert drastically decreased. Things returned more or less to normal and the number of trains to Rupert dropped from six a day to five each week. The population dropped back to approximately 8,000 after the war. In 1947, the Celanese Corporation of America purchased an old US military site on Watson Island and began building the Columbia Celullose pulp mill. Along with similar mills north in Southeast Alaska, the timber industry helped stabilize the regional economy. One of the biggest disappointments for the community - which was still harboring hopes of a local maritime industry - was the sale of the floating drydock and dismantling of the shipyard in 1955. In 1961s, the Prince Rupert airport was built and in 1963 ferry service began with the Alaska Marine Highway System. In 1966, the Queen of Prince Rupert inaugurated service between Prince Rupert and the rest of British Columbia. Interest was also increasing in shipping grain and raw materials to Asia once again, although two major dock fires in 1967 and 1972 hampered those efforts. The long underutilized grain port was expanded The town continued to grow and had a population approaching 18,000 by the mid 1970s. But then changes in the timber and fishing industries began to effect the community. By the mid 1990s both industries had cut back and the town population was beginning to drop. Two incidents significantly hurt the city. First, in 1997, fishermen blockaded an Alaska State Ferry to protest what they considered an unfair salmon allocation in the international salmon treaty. The industry was already only a shadow of what it had been and the blockade had the unintended effect of nearly cutting off tourist and other trade with Alaska. Then the massive Skeena Cellulose

pulp mill went through several shutdowns before closing for good

in the early 2000s. At its peak, the mill had employed nearly

2,000 workers and more than 5,000 other workers were The local population plummeted to just a little over 10,000 and things looked bleak for the local economy. Several unsuccessful attempts were made to restart the pulp mill. Finally, the community turned its attention elsewhere. It looked in two directions, South and West. The rapid expansion of the Alaska cruise ship industry had pretty much bypassed Prince Rupert in the 1990s. But as Alaskan ports became more crowded, Prince Rupert saw an opportunity. It created a port out of vacant waterfront property and was expected to get upwards of 100,000 cruise visitors in 2007. That was barely 10 percent of the total Alaska trade, but it was a start. Congestion of a different kind in Vancouver and Los Angeles was also seen as a opportunity for Prince Rupert. It was also an chance to make Charles Hays' original dream finally come true. By the early 2000s, huge amounts of cargo was being via containers to North America from Asia. So much cargo - mostly in the form of consumer goods - was arriving that congestion became severe at the main west coast ports of Seattle., Vancouver and Los Angeles and significant shipments delays were common. Expansion of those ports to relieve the congestion is next to impossible because of their locations in major metro areas. Besides being closer to Asia and cutting sea time significantly, Prince Rupert also had relatively underutilized CN rail lines into the center of the continent and down the Mississippi River. It also had more than enough waterfront space that could be turned into a massive container port in the Fairview area south of town. The federal and provincial governments committed more than $160 million to the first phase of the Fairview Container terminal that is on schedule for completion in October of 2007. The first phase - which has a capacity of 500,000 container equivalents each year - will employ more than 200 people permanently and is a major boost to the local economy. Plans are already in work for a massive expansion of the container port to a capacity of more than 2 million container equivalents a year. That phase is projected to be complete in 2010 if funding is obtained and would employ more than 400 people. As the economy of Prince Rupert is improving the population has edged back up to approximately 15,000. "There's a hint of destiny

involved," Paul Wells wrote in MacLean's magazine Oct. 26,

2006. "Charles Hays founded Prince Rupert in 1906 in hopes

of making it a key port of trade with Asia.maybe he was just

a century or so ahead of his time."

On the Web:

Dave Kiffer is a freelance writer living in Ketchikan, Alaska. Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us

|