A Sad Chapter of World War II in Alaska Aleuts Relocated for Safety, Yet Many Died At Ward Lake By DAVE KIFFER June 23, 2007

In the grand scheme of World War II, it was only a feint. The idea was to attack American "home" territory to draw attention away from the central Pacific where the Japanese hoped to deal a crippling blow to U.S. forces at Midway and drive the US Navy back to Pearl Harbor or even San Francisco. There was also a symbolic reason for the Aleutians attack that came to light after the war. Japanese officials were convinced that the spring 1942 Doolittle bombing raid on Tokyo had come from US bases in the western Aleutians when in fact it had come from American carriers that had gotten in close to the Japanese home islands.  Historical Photo - Public Domain: Naval Historical Center Department of the United States Navy

But with Japanese forces ashore in the Aleutians, American authorities made one of the most controversial decisions of World War II: To relocate the residents of the Aleutians to Southeast Alaska. Several camps were set up, including one at Ketchikan's Ward Lake. By late August of 1942, between 160 and 200 Aleuts (Federal figures are unclear about the exact number) were living in Ketchikan. Approximately 25 percent, mostly the very young and the very old, would not survive to return to their homes nearly three years later. Lack of Planning Beginning in March of 1942, American military intelligence had warned Alaskan defense officials that a Japanese attack was likely along the 900 mile island chain. On June 3, Japanese planes bombed American facilities at Dutch Harbor and then several days later, Attu and Kiska islands were invaded. More than 40 villagers were captured on Attu and spent the rest of the war in prison camps in Japan. Barely 20 would survive the ordeal and return to Alaska.  Historical Photo - Public Domain; Naval Historical Center Department of the United States Navy

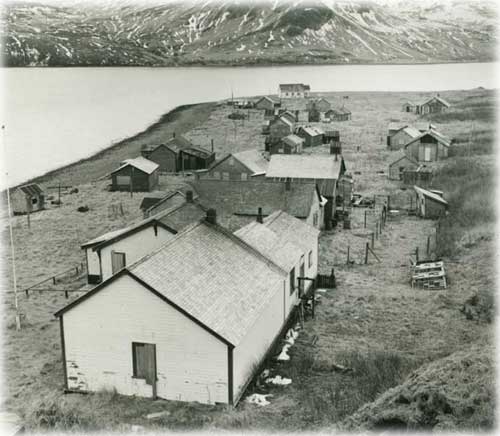

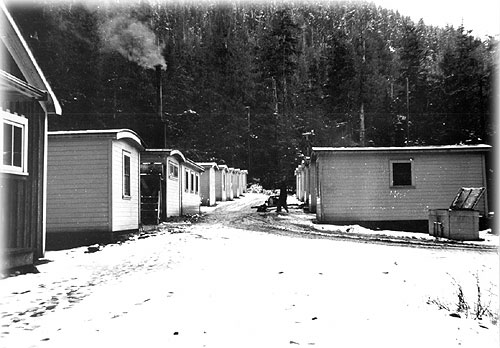

"The evacuation of the Aleuts was a reasonable precaution taken to ensure their safety," according to "Personal Justice Denied," the final report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. " But there was a large failure of administration and planning which becomes evident when the central questions are addressed: Why did the military and civilian agencies responsible for Aleut welfare wait until Attu was actually captured before they evacuated the islands? Why were evacuation and relocation policies not formulated by the government departments most knowledgeable about the danger of an enemy attack they expected? And why was the return of the Aleuts to their homes delayed long after the threat of Japanese aggression had passed?" According to the commission report, the US military had been making improvements to bases in Alaska and in the Aleutians since 1940 in anticipation of the growing conflict coming to Alaska, yet no plan was in place for dealing with any refugees. The result was a hasty relocation. "The Aleuts were relocated to abandoned facilities in southeastern Alaska and exposed to a bitter climate and epidemics of disease without adequate protection or medical care," the commission report noted. "They fell victim to an extraordinarily high death rate, losing many of the elders who sustained their culture. While the Aleuts were in southeastern Alaska, their homes in the Aleutians and Pribilofs were pillaged and ransacked by American military personnel.. In sum, the evacuation of the Aleuts was not planned in a timely or thoughtful manner. The condition of the camps where they were sent was deplorable; their resettlement was slow and inconsiderate. The official indifference which so many Native American groups have experienced marked the Aleuts as well." Of the more than 800 Aleuts relocated to five camps in Southeast Alaska, at least 160 came to Ward Lake (some sources say the actual number was 200), where they were housed a camp that had originally been built in the early 1930s for the Civilian Conservation Corps and meant to hold no more than 70 people.  Courtesy National Archives

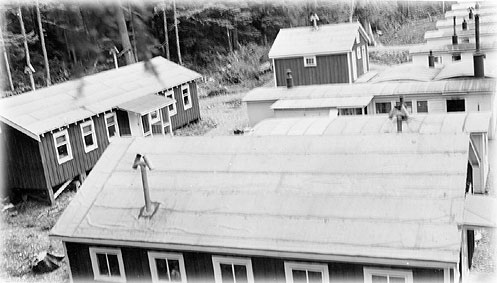

The CCC camp ceased operation in April of 1942 because the CCC had been disbanded with the coming of war in December of 1941. Then the camp was briefly used as a training base for the 10th Army Air Force Rescue Boat squadron which was training in Ketchikan and had been booted out of its winter quarters at the New England Fish Company with the arrival of the summer salmon season. "We then moved to the abandoned CCC Camp at Ward Lake, some eight miles out the north highway from Ketchikan, where with just a little clean-up, was both usable and somewhat isolated from the community," wrote rescue boat squadron member Ralph M. Bartholomew in a squadron history presentation to the "Alaska At War" conference in Anchorage in 1993. "That became the "boot camp" for our Army training as well as our classroom for the navigation, signaling and small boat handling classes." But shortly after the squadron arrived at Ward Lake, the government made the decision to relocate the Aleuts to Southeast and the squadron was moved to the Army Air Field under construction on Annette Island.  University of Alaska Anchorage, ARchives & Manuscripts Dept. Photograph courtesy Ketchikan Museums

Less that a week after the Japanese invaded Attu and Kiska, the US decided to evacuate the villages in the western Aleutians and the Pribilofs. Abandoned canneries were pressed into use at Killisnoo, Funter Bay, and Burnette Inlet. "We were only a given a few hours to pack and we were allowed to bring one suit case each," said Faye (McGlashan) Schlais, who spoke to group of Schoenbar Middle School students last month. She was part of a large group that was intitially sent to the Wrangell Institute. This group - from the villages of Akutan, Biorka, Kashega, Makushin and Nikolski - would form the core of the group that would go to Ward Cove.  Alaska State Library - Historical Collections Photograph courtesy Ketchikan Museums

Initially, US authorities thought that the Ward Lake evacuees would be better off than other groups because they were the only one that would be connected - by an eight mile road - to a population center and they would also be taking over a camp that had been in constant use and not abandoned for some time like the canneries. And since it was clear that the "camp" had been designed to house a group half the size of the Aleut evacuees, building supplies would also be provided to expand the accommodations.  Alaska State Library - Historical Collections Photograph courtesy Ketchikan Museums

"The Aleuts lived neither on the shores of Ward Cove nor those of Ward Lake," Kohlhoff wrote. "The CCC camp did not even have a view of the water that might have been reminiscent of their Aleutian homes. It was instead buried deep in the rainforest." Dorofey Chercasen of Nikolski was even more succinct in his testimony to the relocation commission years later. He said his first impression of the Ward Lake camp was a bad one. "It was like being put in prison," he told the commission. "My home was far away." Faye (Fekla McGlashan) Schlais was asked by the Schoenbar students if she remembered anything good about the camp that she had arrived at on August 24, 1942 as an 18-year-old with nine members of her family from Nikolski. "Nothing," she said. "Nothing at all." Find Your House The Aleuts arrived in Ketchikan at 2 a.m. They were driven to the campsite and essentially told to "find your house" according to Kohlhoff. They were accompanied by Barbara and Samuel Whitfield, the Office of Indian Affairs teacher from Nikolski and her husband who would later leave to join the Coast Guard. Shortly after, Fred Geeslin, an Office of Indian Affairs resettlement officer was also posted to the camp. The CCC camp was nine small cabins and four communal buildings. Each cabin had a small kitchen and a bedroom with two bunk beds. Lumber brought from Wrangell was used to build additional cabins and some furniture, scrap lumber was used for insulation although most of the buildings were far from airtight, according to the Commission Report. The camp also included a school, a church, a laundry and a shower facility that included two stalls.  Alaska State Library - Historical Collections Photograph courtesy Ketchikan Museums

In his book, Kohlhoff also noted the lack of rudimentary health care at the camp which he called the "most serious deprivation." "Based on examination by a visiting Indian Service physician, five Aleuts were sent toTacoma, others too were eventually sent," Kohlhoff wrote. The Commission report also noted that health care was almost non-existent except for rare visits from the Indian Health Service. In talking about the camp with Schoenbar students, Faye Schlais agreed that there was little medical care, but she noted that a local doctor did visit the camp several times and try to help the Aleuts. The government plan was that after getting their camp "in order" the Aleuts would work in the local canneries, but by the time the camp was "habitable" the salmon season was already winding down and there were few jobs for the Aleuts. "Given the odds, Aleut accomplishments at Ward Lake were impressive," Kohlhoff wrote. "They actually improved the facilities. Fred Geeslin remarked that 'these people are the hardest workers I've ever seen.'" A similar conclusion was reached by the Ketchikan Chronicle which visited the camp shortly after the Aleuts arrived and found the forest ringing the sound of hammers and saw and the camp positively reeking of fresh cut lumber. Some Aleuts, like Schlais and her sister, got jobs with Ketchikan businesses. In most ways, it was up to the Aleuts themselves to make things better. The government lumber was all they had been given in addition to small amount of food. Government officials expected them to be able to "live off the land" yet none had any experience hunting or fishing in the rain forest. It was also expected that the Aleuts would find work in the Ketchikan area to support the camp.  Photograph courtesy Ketchikan Museums

A Ketchikan man named Eugene Wacker was living in Ward Cove at the time (his property was called 'Wacker City' for many years). Wacker operated a bus from Ward Cove to town and back and offered to transport the Aleuts who had not been provided any transportation by the government. "Now we were able to shop and ride into town to our jobs. . . . He charged us fare between points, but without his consideration and care we would not have done well for jobs and supplies we needed in town," Chercasen told the Relocation Commission in 1981, adding that Wacker also kept an ear out for opportunities for the Aleuts in Ketchikan. "He came to our camp to tell us about it and drove those who wanted the job into town. He then would also drive us back to the camp after work. . . . Most of us might have had to go to other communities seeking jobs, but because of him we were near our families at camp. . . . Eugene Wacker did this for the three years we were at Ward Lake. " Wacker also found himself as an unofficial advocate for the Aleuts who were not welcomed with open arms by most of the community. There were other local residents who delivered food and supplies to the Aleuts and gave them blankets and other items, but Wacker was truly their primary "friend" in the community. He even occasionally bailed out Aleuts who had been jailed by the police. By the following spring, Harry McCain, Ketchikan's health official, had slapped a "quarantine" on the camp because of what he called a high incidence of both tuberculosis and venereal disease. "There are a large number of service men in and near Ketchikan and neither they nor the civilians should be infected with their (the Aleuts) diseased conditions," McCain wrote to territorial Governor Ernest Gruening on May 19, 1943. "The proprietor of the Totem Lunch inquired whether or not she could refuse their patronage for the reason they are unsanitary and diseased and this was obnoxious to her regular customers besides requiring an unusual amount of trouble sanitizing dishes." McCain asked the governor to move the Aleuts out of Ward Lake and "to some suitable location where they would not have immediate contact with large numbers of people." Other local officials expressed concern that pollution from the camp was running into Ward Lake and damaging the recreation area that had been built only a few years before. Testing of the lake did show a high level of pollution. But at the same time, federal officials were equally concerned about the vices in the city of Ketchikan and the effect they were having on the Aleuts. Coast Guard Captain Fred Zeusler attempted to rebut some of McCain's claims in a letter in the May 22, 1943 Ketchikan Chronicle. "I have been in practically everynative house from Unalaska to Attu, so I know how they live," he wrote. "Their villages were clean and progressive. Their health was good except there was considerable tuberculosis. They did not have gonorrhea or syphilis (back in the Aleutians). I ask you what has the city done to help them in any way? The city has not bettered their condition (by failing to check the rampant bootlegging) and now that they are supposedly diseased you want to throw them out."  Photograph courtesy Ketchikan Museums

The Indian Affairs officer, Fred Geeslin had tried to prevent alcohol from coming into the camp, even going as far as impounding a cab that tried to deliver booze. Local Coast Guard officials offered to provide "survelliance" in the form of a guard for the camp entrance. "Ketchikan was apparently a sin city full of prostitution, venereal disease and drunkenness," Kohlhoff wrote. Acting Governor Bob Bartlett also stepped in and ordered Ketchikan officials to do a better job of policing vice in the community both in relation to both Aleuts and the servicemen. Unfortunately, city officials took that as an excuse to crackdown.on the Aleuts. "The ensuing crackdown hurt Aleuts," Kohlhoff wrote. "They regarded it as unfair discrimination and harassment." Arrests of Aleuts in Ketchikan rose significantly over the winter. But there was an even greater concern at the camp. In September, a just a month after arrival, 13-year-old Frank Bezekoff died. By Christmas three more camp members had died. Several had been sick when they arrived at Ward Lake, but the lack of treatment meant that - especially with the pneumonia that plagued the camp - many more Aleuts would die in the next three years. Federal estimates place the number at nearly a quarter of the camp residents, the highest death rate of any of the Alaskan relocation centers. Many were buried at Bayview Cemetery, but there were also graves in the woods near the camp. Conditions had not significantly improved by the following May and the Ketchikan City Council - after a lengthy debate - asked the federal government to either improve the medical conditions at the camp or find another location for the Aleuts. The federal government offered to provide more money for Ketchikan health officials to deal with the problem, but local officials replied that they wanted the federal government to build a Native health facility in Saxman as "part of the war effort." That proposal went nowhere. And neither did the Aleuts for another two years. They also generally disappeared from the local public debate. About the only time they appeared in either the Ketchikan Chronicle or the Alaska Fishing News over the next two years was when they visited the Ketchikan Hospital and the USO Club around Christmas time to sing carols. "A handful of Ketchikan residents was privileged Sunday to see the members of the Aleut Colony at Ward Lake in some of the pageantry that was transplanted in this new world by the Russians," The Ketchikan Chronicle reported on January 8, 1945. "The Aleuts are at the present time the western hemisphere's only war refugees they have fulfilled the traditional role of refugees being sheltered in limited, unwholesome quarters, exposed to the white man's vices and given little to do to make them forget what the war has meant to their homelands." By this time, the Japanese had been long been driven out of their toehold in the Aleutians. Battles in the summer of 1943 had cleared Attu and Kiska. The US government initially approved plans to resettle the Aleuts late in 1943. But nothing was done and no government records exist showing why the plan was shelved for more than a year. Going home, finally Finally, just before Christmas of 1945, it was announced that the Aleuts would be "resettled." But even that good news was tempered by the fact that officials were also saying that some of the smaller villages would not be resettled in order to concentrate the Aleuts in larger communities and allow the government to provide services such as schools more "efficiently." On April 17, the majority of the Ward Cove Aleuts were taken on board a transport and headed north to pick up refugees from Burnett Inlet and Killisnoo. When they arrived back in the Aleutians in the summer, they discovered that many of the villages had been ransacked and that many of the houses had been burned by US troops to keep them from being used by Japanese troops. The distinct cupola of the Russian Orthodox Church at Nikolski was used for target practice by American troops, according to " Making it Right: Restitution for Churches Damaged and Lost During the Aleut Relocation" written in 1993 by Barbara Smith and Patricia Petrivelli. Once again, the Aleuts had to scramble to make sure everyone was housed by the end of the summer and the cold Aleutian winter rolled in. Despite the damage, most Aleuts chose to stay in the Aleutians but a few like Faye Schlais, Anna Frank, Vera Gilbert and Johnny Dyakanoff returned to Ketchikan and raised families. In the 1950s, Aleut leaders joined the Japanese Americans who had been interned during the war in lawsuits against the federal government. In 1987, Congress finally passed

legislation that granted the Aleuts restitution amounting to

$12,000 each plus more than $20 million for property damage.

Much of that money went to programs administered by the Aleut

Native Corporation.

On the Web:

Dave Kiffer is a freelance writer living in Ketchikan, Alaska. To republish this article, the author requires a publication fee. Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us

|