From Iwo Jima to Icy Strait, the long, colorful history of the Acushnet By DAVE KIFFER August 23, 2006

The Coast Guard is doing an environmental assessment on both the 62-year-old Acushnet and the 63-year-old Kodiak based cutter Storis. It hopes to decide in the next few months whether the ships should be surplused and whether or not other ships will be home-ported in Ketchikan and Kodiak to replace them.  USCG photo by Petty Officer Christopher D. McLaughlin - Aug. 29, 2005

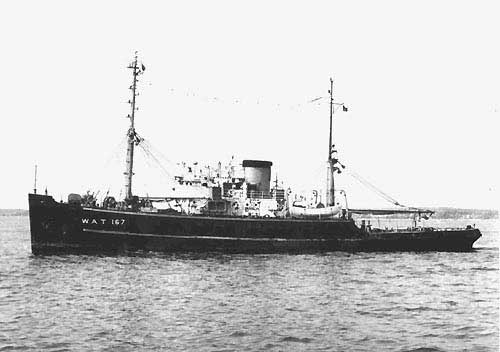

The register report also states that the GSA would then either transfer ownership of the vessels to another state, local or federal or international entity or scrap the ships. Part of the study will also determine whether or not the replacement ships will go to Ketchikan and Kodiak. The Acushnet began its sea life during World War II as the USN Shackle, a rescue and salvage ship. The 213-foot Shackle was built at Basalt Rock Co. in Napa, California between October 1942 and February 1943. It was commissioned on Feb. 5, 1944 with Lt. Charles Jenkins as its first commander. "Following shakedown out of San Diego, Shackle proceeded to Pearl Harbor..she continued to Midway where she cleared the entrance channel of the USN Macaw, a submarine rescue ship that had gone aground," according to the US NavSource website. "Brief duties at Eniwetok, Guam and Saipan followed and in late 1945, she commenced preparations for the assault on Iwo Jima."  After 1958, the Acushnet was painted white and its forward boom removed. Photo Courtesy USCG (Official Coast Guard photograph)

Off Okinawa, the Shackle was kept busy doing salvage work on numerous naval vessels, many of whom had been hit in kamikaze attacks. In one month alone, the Shackle helped pump out and repair more than 20 other ships. The Shackle was also involved in the some of the last action of the war, as it was nearby the battleship Pennsylvania when it was hit by torpedoes near Okinawa on Aug 12, 1945 two days before Japan surrendered. The Shackle performed damage control and salvage work on the stricken battleship. After the surrender, the Shackle joined a large contingent of US vessels in Tokyo harbor and worked as clearing dock areas around Japan until it returned to Pearl Harbor and then the West Coast. For its service in the Pacific, the Shackle was awarded three battle stars. On Aug. 23, 1946, it was decommissioned by the Navy and transferred to the Coast Guard which renamed it the Acushnet. The Acushnet was initially designated a tug boat and assigned to Portland, Maine where it frequently rescued fishermen and boaters in distress. A story of one of its adventures in those years was recounted by former crewman Sid Morris in SeaClassics magazine in 1965 and republished on SITNEWS in 2003. Morris was onboard the Acushnet out of Portland in 1951-1952 and wrote of a spectacular rescue in which the Acushnet helped save crewmen from one of two tankers that had broken apart in a storm off Cape Cod on Feb. 18, 1952. "The icy, biting winds swept in at noon and, by dusk, their velocity had built up to 35 knots, that night the big black ship surged and rolled at the end of the Maine State Pier as if she were bucking 30 foot swells" Morris wrote about the storm. "The dawn greeted us with a ubiquitous carpet of snow and ice. All our weather decks were covered with four feet of snow and our mooring lines had disappeared into the tremendous drifts." The crew received the word to respond to the sinking tankers, the SS Pendleton and the SS Fort Mercer. It took nearly more than 20 minutes to clear enough snow from the decks of the Acushnet to get underway, Morris wrote. Crewmembers had to scramble through the blizzard to get to the ship before it cast off. Even the captain had to commandeer a small boat and catch up with the Acushnet, climbing up a rope over the stern as the vessel left port.  Official USCG Photo; ELC 1CGD; photo by Richard C. Kelsey, Chatham, Mass.

When the Acushnet arrived on scene of the disaster, some 50 miles south of Nantucket Island, the surviving crew members from the bow of Fort Mercer had been rescued by the crew of the Coast Guard cutter Yakutat. The Acushnet steamed 25 miles away to the remains of the Fort Mercer's stern where the Coast Guard ice breaker Eastwind was trying pull the survivors off one at a time but the tanker was in danger of capsizing and the weather was so severe that one of the crewmen nearly drowned as he was being pulled from the tanker. On board the Acushnet it was decided that a better course was to bring the tug alongside the Fort Mercer so that the survivors could jump onto the tug in a group, despite the nearly 60 foot waves battering both ships. "Each coming wave swept the two vessels closer and closer then the nightmare of the sea exploded in our faces; the two sterns rose up on the same swell and clashed together with the full impetus of the raging ocean," Morris wrote. "I was knocked down to my knees as the entire ship seemed to drop right out from under my not-too-steady sea legs." But the Acushnet's captain, Lt. Commander John H. Joseph, a 25-year veteran of the Coast Guard, held steady, Morris wrote, and seven crew members were pulled off the broken tanker before the Acushnet had to pull back.  Official USCG Photo; photographer unknown.

The praise for the Acushnet's work on the rescue was repeated in a report on the Pendleton and Mercer rescues on the Coast Guard history website. Ensign Ben Stabile who was later to become a USCG Vice Admiral was on the Cutter Unimak which was also on scene and witnessed the rescue. "The Acushnet seamanship was the most outstanding I've ever seen," Stabile wrote in the report. "How the CO managed to execute without damaging the ship or losing anyone is beyond me." In 1968, the Acushnet was designated an oceanographic vessel and used in San Diego as to support the National Data Buoy Project. In 1971, she was transferred to Gulfport, Mississippi where in 1978 she was reclassified again, this time as a medium endurance cutter. Her main role was to enforce maritime laws in the Gulf of Mexico, the Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea. Two years later, the Acushnet played a played a key role in the Coast Guard's response to the famous Mariel boatlift of 1980. The Cuban exodus started when a group of Cubans entered the Peruvian Embassy in Havana seeking political asylum. A standoff ensued and in order to defuse the situation Cuban leader Fidel Castro announced that any Cubans wanting to emigrate immediately could leave via the harbor at Mariel, which was some 20 miles west of Havana. What followed shocked both the Cuban and American governments as nearly 125,000 Cubans sought to leave the island on more than 1,500 boats of varying shape and sizes over the next three months. The Acushnet was one of more than two dozen large Coast Guard vessels to arrive on scene and try to sort out the chaos, as well to help the thousands of refugees, many of whom where floating across the Gulf of Mexico on overloaded boats and fragile rafts.  USCG photo by PA3 Christopher D. McLaughlin.

"While patrolling alone north of Mariel Bay, cutter Acushnet was approached by three Cuban gunboats, which, according to Acushnet crewman Bob Dyche, 'were circling us, herding us in effect, maneuvering in such a way as to force us into a violation of their territorial waters. They were. . .often within 60 feet of us, severely limiting maneuverability; we could not break free without hitting at least one of them,'" Stabile reported Dyche said. He quoted Dyche at length about the seriousness of the encounter. "It must be understood that many of the boats leaving Mariel were completely unseaworthy; virtually all were grossly overloaded and many were already in serious trouble when they reached "the line," the boundary between Cuban territorial waters and the open sea. Because of the very real danger to human life, we consistently patrolled as close to the line as possible," Dyche said. Dyche said that the it was clear the Cuban gunboats were trying to "foment an international incident" and the Coast Guard contacted the US Navy for help. "The gunboats had begun to give us a bit more room but were still moving us ever closer to the line; our plot made it clear that their plan was working, " Dyche recalled.

In 1990, the Acushnet was moved to Eureka, California and put on lengthy patrols up and down the West Coast as far as the Bering Sea. In 1998, the ship and its complement of approximately 100 crewmembers and support staff were redeployed again, this time to Ketchikan, where is continues patrolling the waters from Dixon Entrance to the Bering Sea for months at a time.

Contact Dave at dave@sitnews.us

|