July 10, 2007

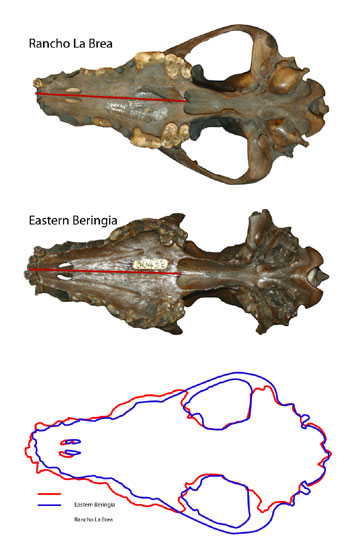

"Our results are surprising as the unique attributes of Alaskan Pleistocene wolves had not been previously recognized and show that wolves suffered an extinction at the end of the Pleistocene," said Blaire Van Valkenburgh of the University of California, Los Angeles. "If not for their persistence in the Old World, we might not have wolves in North America today. Regardless, the living gray wolf differs dramatically from that which roamed Alaska just 12,000 years ago." The ancient gray wolves lived in Alaska continuously from at least 45,000 years ago - probably earlier, but radio carbon dating does not allow for the establishment of an earlier date - until approximately 12,000 years ago, Van Valkenburgh said. The gray wolf is one of the few large predators that survived the mass extinction of the late Pleistocene. Nevertheless, wolves disappeared from northern North America at that time. To further explore the identity of Alaska's ancient wolves in the new study, the researchers collected skeletal remains of the animals from Pleistocene permafrost deposits of eastern Beringia and examined their chemical composition and genetic makeup. The scientists analyzed DNA samples, conducted radio carbon dating and studied the chemical composition of ancient wolves at the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History. They then compared the results with modern wolves and found that the two were genetically distinct. Remarkably, they discovered that the late-Pleistocene wolves were distinct from existing wolves, both genetically and in terms of their physical characteristics. None of the ancient wolves were a genetic match for any modern wolves, they report. Moreover, the animals' skull shape and tooth wear, as well as a chemical analysis of their bones, all suggest that eastern Beringian wolves were specialized hunters and scavengers of extinct megafauna. "The ancient Alaskan gray wolves are all more similar to one another than any of them is to any modern North American or modern Eurasian wolf," said study co-author Blaire Van Valkenburgh, UCLA professor of ecology and evolutionary biology. The ancient gray wolves were not much different in size from modern Alaskan wolves, although their massive teeth and strong jaw muscles were larger. They were capable of killing large bison, Van Valkenburgh said. "The ancient wolves had relatively more massive teeth and broader skulls with shorter snouts, enhancing their ability to produce strong bites," Van Valkenburgh said. "In addition, the studies of their tooth wear and fracture rate showed high levels of both, consistent with regular and frequent bone-cracking and -crunching behavior." Those characteristics probably came in handy in ancient Alaska, where the ancient wolves faced stiff competition for food from some very formidable competitors, she added, including lions, enormous short-faced bears, and saber-tooth cats. During periods of intense competition among predators, modern-day wolves will also consume carcasses more fully, ingesting more bone and eating faster, which increases the risk of tooth fracture. The ancient wolves suffered many broken teeth and tooth fractures, she said. Van Valkenburgh has also studied tooth fractures in ancient animals at Los Angeles' Rancho La Brea Tar Pits and in modern lions, tigers, leopards, puma and wolves. The ancient large mammals broke their teeth frequently when they ate, crunching the bones of their prey much more often than their modern counterparts. Why? "Because they were hungry, which may have been because it was difficult to catch and hold onto prey when there was much competition and theft among carnivores, forcing them to eat quickly," said Van Valkenburgh, who won a UCLA distinguished teaching award in June. "They were probably living at such high densities that we have difficulty even imagining, with frequent encounters between carnivores." The saber-toothed cat and other large mammals became extinct about 10,000 to 11,000 years ago when their prey disappeared due to factors that included human hunting and dramatic global warming at the end of the Pleistocene, Van Valkenburgh said. Prior to the new research, it was not known whether today's gray wolves in Alaska and elsewhere descended from ancient gray wolves that roamed those areas in the Pleistocene or whether there was an extinction or near extinction of the gray wolves from northern North America. Does the research have implications for global warming today? "When environmental change happens very rapidly, animals cannot adapt, especially when the few places for them to move as habitats shrink; they are more likely to go extinct," Van Valkenburgh said. "It was a rapid climate change in the late Pleistocene." The long-ago demise of this specialized wolf form may portend things to come for specialized groups of existing predators, Van Valkenburgh said. For example, a unique type of nomadic North American gray wolf was recently discovered. Their packs migrate across the North American tundra along with caribou and keep their numbers in check. In contrast, all other wolves are territorial and non-migratory. "Global warming threatens to eliminate the tundra and it is likely that this will mean the extinction of this important predator," she said. The lead author on the research, Jennifer Leonard, earned her doctorate from UCLA and is now on the faculty of Sweden's Uppsala University. She studied the DNA of more than a dozen wolves that lived 12,000 to 45,000 years ago. Other co-authors are Carles Vilà, a faculty member at Uppsala University; Kena Fox-Dobbs and Paul Koch from the department of Earth and planetary sciences at the University of California, Santa Cruz; and Robert Wayne, a UCLA professor of ecology and evolutionary biology. The research was federally funded by the National Science Foundation. Sources of News:

Publish A Letter on SitNews Read Letters/Opinions

|

||