A Practice in HealthBy John Cross

January 25, 2020

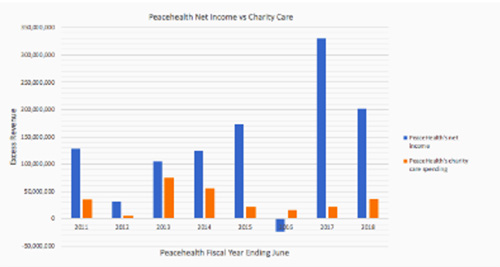

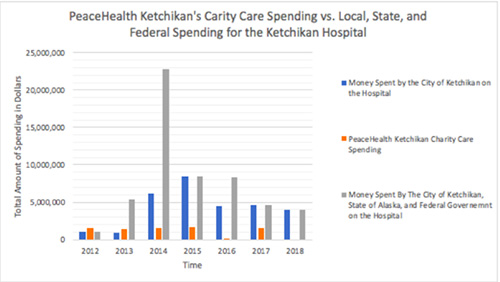

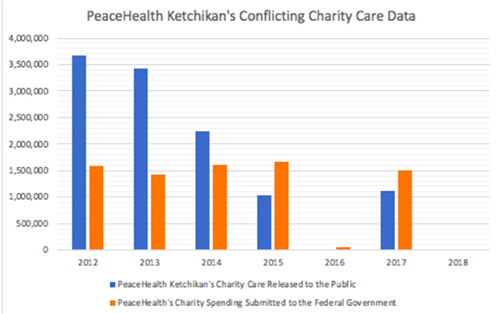

Corporate Outlook. At the corporate level, PeaceHealth’s fiscal situation is the envy of hospitals across the nation. PeaceHealth’s operating margin is well ahead of its peers in the hospital industry. In 2018, the standard operating margin for a not-for-profit hospital was 2.1 percent (Paavola, 2019), PeaceHealth’s 2018 operating margin was 3.4 percent, nearly two-thirds above its hospital companions in the not-for-profit class (Willig et al. 2019). PeaceHealth has managed to expand its profit margin by charging higher prices to patients and their insurance networks. These higher prices have resulted in record profits year after year. In the last two years alone PeaceHealth has generated untaxed profits of over half a billion dollars. PeaceHealth averages 133 million dollars of ?untaxed? “net income”, or profits, each year (Figure 1). How has PeaceHealth become so profitable? Well, one likely explanation is the Affordable Care Act. Federal law requires hospitals to provide medical treatment to all patients regardless of their ability to pay. Before the Affordable Care Act, low income and uninsured patients often could not afford their hospital bills, forcing hospitals to provide large amounts of free medical care. After the ACA expanded Medicaid, the uninsurance rate decreased for low-income individuals and families. The decrease in the uninsurance rate meant that there were far fewer low-income patients who could not afford their medical care. Because fewer patients required financial assistance, hospitals found themselves offering significantly less charity care. In 2014, under the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, hospitals in expansion states observed a twenty-five percent reduction in uncompensated care (Dranove, David et al. 2017). PeaceHealth operates hospitals in Alaska, Washington, and Oregon. The hospitals in these states experienced dramatic reductions in uncompensated care after Alaska, Washington, and Oregon expanded Medicaid. In 2014, the year before the Medicaid expansion, PeaceHealth calculated that it “gave” $113,821,450 in medical care to patients who could not afford treatment. In 2015, the first year of the Medicaid expansion, PeaceHealth calculated that it “gave” $73,670,162 in medical care to patients who could not afford treatment (Figure 1). PeaceHealth experienced a forty-million-dollar reduction in uncompensated care thanks to the Medicaid expansion. This meant that PeaceHealth benefitted from the expansion in two ways. In the first sense, PeaceHealth was able to charge Medicaid for what previously would have been written off as charity care. For PeaceHealth, this meant that the State of Alaska, Washington, and Oregon were paying the medical costs of patients who gained coverage through the Medicaid expansion. In 2011, Medicaid paid roughly 11 percent of PeaceHealth’s revenues, in 2015, after the expansion, it accounted for 15 percent of the Corporation's revenues (KPMG 2012; KPMG 2015). The increase in Medicaid revenues substantially increased PeaceHealth’s profits. Because PeaceHealth qualifies as a Disproportionate Share Hospital the Medicaid expansion increased PeaceHealth’s profitability. Medicaid pays DSH 107 percent of the cost of providing medical treatments (Cummingham, Rudowitz et al. 2017). If Alaska, Washington, and Oregon did not participate in the Medicaid expansion, PeaceHealth would not have received the lucrative DSH payments for Medicaid patients who earn between 100-138 percent of the poverty line. For PeaceHealth, this would have resulted in Medicaid covering the medical costs of fewer patients. This, in turn, would have negatively impacted PeaceHealth’s profitability and would have increased PeaceHealth’s uncompensated care costs (Dranove, David et al. 2017). Along with this, the Medicaid expansion significantly reduced how much PeaceHealth was spending on charity care. A responsible not-for-profit hospital would have responded by ensuring that its charity care spending reflected the benefits provided by the Medicaid expansion and the benefits of being a tax-exempt corporation. But, PeaceHealth did the exact opposite, the Corporation slashed how much it was spending on charity care and placed an emphasis on expanding its profits (Figure 1). PeaceHealth has dramatically reduced its charity care spending but continues to pay no corporate taxes, no income taxes, and no property taxes. Undeniably, PeaceHealth’s tax status cost communities more in foregone tax revenue then they receive in charity care. PeaceHealth is a profitable hospital system that masquerades as a “not-for-profit” hospital in order to receive preferential tax treatment. On top of this, multiple lawsuits have been filed against PeaceHealth. These lawsuits argue that the Corporation has overbilled patients, denied patients certain healthcare procedures, and has refused to offer services that do not align with the hospital’s Catholic views. These lawsuits illustrate that the very communities PeaceHealth claims to be serving are being damaged in PeaceHealth’s pursuit of greater profits and its reduction in charity care spending. PeaceHealth, in exchange for being a “not-for-profit,” is required to offer free or affordable medical care to those who cannot afford their medical bills, something the Corporation has neglected to do. PeaceHealth believes that being tax-exempt is an entitlement, with little-to-no strings attached (Whitol, 2019; Vencil, 2019). Look no further than their actions in Ketchikan. PeaceHealth Ketchikan's Hospital Practices. The City of Ketchikan has been responsible for all hospital construction projects in the city. The City built the hospital, constructed the emergency department, and funded the 2014 hospital expansion. The City of Ketchikan’s current hospital lease with PeaceHealth Ketchikan states that PeaceHealth Ketchikan will, “Rent, operate, and maintain [the hospital facilities].” And is expected to provide, ”A reasonable volume of charity care.” While the City of Ketchikan is required to, “Make structural changes. . . [and] Obtain bonds for structural alterations exceeding $10,000.” (Community Forum, 2019). In 2014, Ketchikan voters approved a forty-three million dollar bond package financing the hospital expansion project. Initially, projected to cost forty-three million dollars, unanticipated costs, interest, and overages will end up costing community taxpayers ninety-five million dollars. So, the City of Ketchikan has held up its end of the lease between the City and PeaceHealth Ketchikan, has PeaceHealth Ketchikan? At the beginning of the lease, PeaceHealth Ketchikan spent approximately four-million dollars a year on charity care (Figure 2). But, as time has passed, PeaceHealth Ketchikan has put profits over the well-being of the community. A preference illustrated by PeaceHealth Ketchikan reducing its published charity care spending by 69 percent and its implementation of aggressive billings practices. The very same billing problems plaguing PeaceHealth in Washington and Oregon have been incorporated into the billing practices of PeaceHealth Ketchikan. Just as PeaceHealth was being accused of having predatory billing practices in Washington and Oregon, twelve complaints from Ketchikan residents were submitted to the Better Business Bureau against PeaceHealth Ketchikan. The claims were filed as a “Billings/Collection Issue.” These billings issues first appeared in 2017 and have continued unabated since (Kheiry, 2017). With the former CAO of PeaceHealth Ketchikan, Ed Freysinger, stating to the City Council that the, ”Hospital has heard concerns that patient bills were going to collections before they were resolved.” (Transmittal Memorandum, 2019) Moreover, PeaceHealth Ketchikan has transitioned away from a hospital that puts patients first, into a hospital that places profits ahead of patient affordability. PeaceHealth Ketchikan has dramatically reduced the amount of free or affordable medical care it is willing to provide to the community. From 2012 to 2017, PeaceHealth Ketchikan reduced its published charity care spending by 69 percent. The reduction in PeaceHealth Ketchikan’s charity care spending occurred just as Ketchikan was spending upwards of ninety-five million dollars on the hospital expansion process. PeaceHealth Ketchikan responded to this massive community investment by implementing predatory billings practices and by significantly reducing its charity care spending (Figure 2). PeaceHealth Ketchikan’s Certificate of Need. Unfortunately, this adventure does not stop here. Part of the 2014 hospital expansion process required PeaceHealth to submit a document called a Certificate of Need to the State of Alaska. The Certificate of Need process ensures that state funds are spent on responsible organizations that merit funding. On the Certificate of Need, PeaceHealth Ketchikan estimated that it would be spending approximately 4,258,278 dollars per year on charity care from 2014-2016. In actuality, PeaceHealth Ketchikan spent approximately two million dollars on charity care in 2014 and slightly over one million dollars on charity care for 2015, with no data available for 2016. (Certificate of Need, 2014) Not only has PeaceHealth Ketchikan misinformed the State of Alaska about its charity care spending, but the local hospital has significantly altered the charity care numbers released to the public. Over the years, PeaceHealth Ketchikan has published numerous reports outlining how much it has spent on charity care in Ketchikan. But, the charity care numbers PeaceHealth Ketchikan has released to the public are fundamentally different than the charity care numbers PeaceHealth Ketchikan has submitted to the Federal Government (Figure 3.) There are two ways of approaching the differing charity care submissions. The first approach is to assume that the charity care spending PeaceHealth Ketchikan has released to the public is true. If this is the case, then the charity care numbers PeaceHealth Ketchikan has submitted to the Federal Government are inaccurate, placing the hospital in violation of numerous federal laws. The second approach is to assume that the charity care numbers PeaceHealth Ketchikan has submitted to the Federal Government are true. This approach does not place the company in violation of federal laws but does create several other problems. If the charity care numbers PeaceHealth Ketchikan submitted to the Federal Government are true, then the charity care numbers the hospital submitted to the State of Alaska on its Certificate of Need document are false. This means that PeaceHealth Ketchikan submitted false and inflated charity care numbers to the State of Alaska, just as the State of Alaska was debating whether it should award PeaceHealth Ketchikan with a multi-million dollar hospital expansion grant (Figure 3). Moreover, if the charity care numbers released to the public are indeed incorrect, then PeaceHealth Ketchikan published misleading charity care information just as the community of Ketchikan was preparing to vote on the multi-million-dollar hospital expansion bond. It appears as though PeaceHealth Ketchikan misled the State of Alaska and the community of Ketchikan about its charity care spending in the hopes of attaining tens-of-millions of dollars in community investment. PeaceHealth Ketchikan did not respond to requests for comment. It is important to note that PeaceHealth Ketchikan did not require funding from the State of Alaska and the community of Ketchikan in order to keep the facility open. In 2014, PeaceHealth Ketchikan had a profit margin of 3.7 percent (Review of PeaceHealth Ketchikan Medical Center Addition Project, 2014). Fast forward to 2019, and the Ketchikan facility had an operating margin of 6.3 percent (Ivantage, 2019). In 2016, PeaceHealth Ketchikan spent forty-six thousand dollars on charity care, the then CAO of PeaceHealth Ketchikan, Ken Jones, had a total compensation of $389,800. PeaceHealth Ketchikan paid its CAO nearly ten times what the local non-profit hospital spent on charity care. Currently, the Corporation of PeaceHealth has six executives who make over one million dollars, and eleven other executives who make between half-a-million and one-million dollars. PeaceHealth has been blunt about how it views charity care spending, with the CEO of PeaceHealth, Howard B Graman, stating to the Oregon legislature that, “We should not be using charity [care] as a goal to achieve, but rather as a cost to be reduced” (Testimony on HB 3034, 2015). Spending ninety-five million dollars on subsidizing a profitable local hospital was a mistake. There are scores of more important projects in the community that deserve immediate funding. One out of every five children in Ketchikan suffers from food insecurity (2019-2022 CHNA). One out of every five children in Ketchikan will not graduate from high school (2019-2022 CHNA). Half of all women in Ketchikan have suffered from domestic violence or sexual assault (Kheiry, 2013). One out of every three women in Ketchikan have been raped (Kheiry, 2013). Now, would spending ninety-five-million dollars on these tragedies be a better use of State and local funds? One can only guess. But, considering that after the community of Ketchikan funded the hospital expansion project-PeaceHealth Ketchikan responded to this by slashing its charity care spending and implemented aggressive billings practices. Questions need to be asked about the value of PeaceHealth Ketchikan’s presence in the community. The City of Ketchikan needs to consider the actions of PeaceHealth Ketchikan when it debates whether to extend PeaceHealth’s hospital lease. *All dollar values present have been converted into September 2019 dollars.

Figure 1. PeaceHealth's Annual Net Income vs. Charity Care. PeaceHealth's net income statements were calculated from PeaceHealth's annual tax filings. PeaceHealth's charity care spending was determined from the Schedule H Form.

Figure 2. PeaceHealth Charity Care Spending vs. State, Local, and Federal Spending on the Ketchikan Hospital. PeaceHealth Ketchikan's Charity care spending was pulled from the: Ketchikan's Community Health Need Assessment and PeaceHealth Ketchikan's Community Update. The money spent by the City of Ketchikan on the hospital was determined from the hospital spending in the City of Ketchikan's annual budget. The State of Alaska and Federal Government's contributions were determined from PeaceHealth's Certificate of Need, grant reports published by the State of Alaska, and PeaceHealth disclosures on donations received.

Figure 3. PeaceHealth Ketchikan's public released charity care data compared to the charity care data submitted to the Federal Government. The charity care data submitted to the Federal Government was obtained through Freedom of Information Requests. PeaceHealth Ketchikan's Charity care spending was pulled from the: Ketchikan's Community Health Need Assessment and PeaceHealth Ketchikan's Community Update. Questions:

John Cross Works Cited

Editor's Note:

Received January 01, 2020 - Published January 25, 2020 Related Viewpoint:

E-mail your letters

& opinions to editor@sitnews.us Published letters become the property of SitNews.

|

||||||