How 80 Coasties saved an Alaskan town during the Spanish Influenza pandemic

May 24, 2020

The Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919 affected nearly every corner of the world. It caused the deaths of between 25 and 50 million people, more than those who died in World War I. Even in regions with the most advanced medical care then available, Spanish Influenza would kill approximately 2 to 3 percent of all victims.

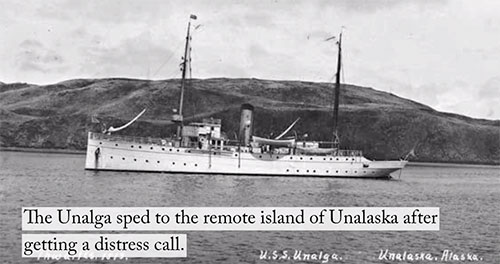

Medical care in the remote territory of Alaska was not advanced. When the pandemic arrived in the spring of 1919, it wiped out entire villages. At this point, Alaska was “an American colony [which] occupied a political status somewhere between a government protectorate and an industrial resource.”[1] The presence of federal government assets was minimal. On May 26, 1919, USS Unalga was patrolling in Seredka Bay off Akun Island, in Alaska’s Aleutian Island chain. World War I had ended just six months prior, so – like all other Coast Guard ships – Unalga and its crew were still technically under the U.S. Navy. At 190 feet, the Unalga’s white hull was only somewhat longer than the Fast Response Cutters patrolling Alaska’s waters today. And while Unalga’s daily operations were fundamentally similar to today’s FRCs, they were significantly broader. An Alaskan patrol in 1919 could consist of law enforcement boardings of fishing and sealing vessels; inspecting canneries; transporting mail, supplies, passengers, and prisoners; rescuing shipwrecked or stranded victims; rendering medical care; acting as a floating court; and resolving labor disputes. The Unalga was resting at anchor following a routine day of seamanship and signals training. Around 1600, an urgent radio message arrived. The settlement of Unalaska on nearby Unalaska Island was suffering from a severe outbreak of Spanish Influenza. The commanding officer, Senior Captain Frederick G. Dodge, prepared to get the Unalga underway at dawn. That night, Unalga received another radiogram: the region around Bristol Bay, on the southwestern Alaskan mainland, also needed urgent assistance coping with an outbreak. Captain Dodge faced a dilemma: the Unalga could not be in two places at once. He chose to head for nearer Unalaska to assess the situation. Remote even today, in 1919 Unalaska and adjacent Dutch Harbor were tiny villages with a combined population of about 360 people, mostly of Aleut or mixed Russian-native ancestry. There was only one doctor on the island. The Unalga’s crew disembarked to a horrific discovery. Nearly the entire settlement was infected, including the only doctor and all but one operator at Dutch Harbor’s small U.S. Navy radio station. The situation was critical; as historian Alfred Crosby wrote in America’s Forgotten Pandemic, “very large proportions of isolated populations tended to contract Spanish Influenza all at once. The sick outnumbered those doing the nursing. The sick, therefore, lacked fluids, food, and proper care, which caused very high death rates… effective leadership was vital to keeping death rates down. If complacency, incompetence, sickness, or bad luck crippled the ability of the leaders to react efficiently to the pandemic, then Spanish Influenza could be as deadly as the Black Death.” It would now fall upon the men of the Unalga to provide this lifesaving leadership and medical care. Out of the Unalga’s crew of approximately 80, the only men on board with advanced medical training were ship’s surgeon LTJG Dr. F.H. Johnson (U.S. Public Health Service), LT E.W. Scott (U.S. Navy Dental Corps), and Pharmacist’s Mate 1/class E.S. Chase. These three men started coordinating the town’s medical care. Together, they rounded up a volunteer medical crew that kept growing until it included personnel drawn from every department on board the cutter. From May 26 to June 4, Unalga was the only resource keeping the inhabitants of Unalaska alive. Captain Dodge decided on his own initiative to feed the entire town using the cutter’s food stores. Crewmembers started by delivering 350 Unalga-prepared meals the first day; by the height of the pandemic they were delivering more than 1,000 meals daily. Villagers considered the ship’s emergency rations to be somewhere between awful and lousy, but sustaining. Every crewmember engaged in some aspect of the relief work. Nicknamed “gobs,” those not directly involved caring for the sick provided logistical support, such as keeping people’s fires going or helping prepare or deliver food. Other crewmen took over operation of the Navy radio station in Dutch Harbor. They even built a temporary hospital outfitted with plumbing and electrified by the cutter’s power plant. Caring for the sick and burying the dead was an exhausting and emotionally challenging undertaking. Death by “The Spanish Lady” (the disease’s elegantly macabre nickname) was often horrific, with victims frequently suffering from double pneumonia drowning because their lungs filled with blood and fluid; when they died it would pour out of their noses and mouths. The crewmembers nursing the sick had no protective equipment besides cloth facemasks, leaving them highly exposed to infection. Several became ill, including Captain Dodge. He determined that he was well enough to remain in command and later recovered, as did all his crewmen. They couldn’t save everybody. The Unalga’s crew ultimately buried about 45 victims beneath white wooden Russian Orthodox crosses in Unalaska’s cemetery. Captain Eugene Coffin, one of the Unalga’s department heads, recorded the men’s exhaustive efforts in his diary. The crew of the Unalga also had to care for the children of the deceased or incapacitated. Unlike seasonal flu, Spanish Influenza most severely affected young adults, probably because it provoked an overreaction in the victims’ immune systems. This had the tragic effect of creating a number of orphans who – even if not infected – were in danger of starving, freezing, or getting eaten by now-feral dogs, which the Unalga’s crew described as more akin to ravenous wolves. Unalaska had an orphanage, the Jesse Lee Home, but when it became full, Captain Dodge requisitioned a vacant house and named it the “USS UNALGA Orphan Home.” When that also became full, Dodge started housing children in the town jail. Among them was Benny Benson, who later designed the Alaskan flag. Peter “Big Pete” Bugaras, the Unalga’s master-at-arms – normally responsible for enforcing ship discipline and handling prisoners – decided he would start caring for the orphans. Bugaras had a reputation as “the strongest man in the Coast Guard Service,” and was described as “Greek by birth, a born fighter of men, and protector of all things helpless and small.” Burly yet big-hearted, Bugaras took full responsibility for running the UNALGA Orphan Home. He had his team fashion clothes for the children by crudely tracing outlines of their bodies on bolts of cloth, and cutting them out. Several recovered women in the village were appalled to see Bugaras enthusiastically scrubbing children clean with the same technique he used on dogs, but by all accounts the little ones loved him. Help arrived on June 3, when the famous Coast Guard Cutter Bear moored. Under the combined efforts of the two crews, many of the surviving victims began to recover and the pandemic began to subside. The town’s final death occurred June 13. The sailors’ care had been somewhat rough-hewn but it was ultimately effective. The mortality rate in Unalaska was around 12 percent, compared to other areas in Alaska that experienced up to 90 percent mortality rate. The early 20th century Coast Guardsmen of the Unalga were far from saints, but for years later the inhabitants of Unalaska remembered them as saviors. Community leaders like Russian Orthodox priest Dimitrii Hotovitzky (irreverently referred to by some of the English-speaking inhabitants as “Father Hot Whisky”) and Aleut Chief Alexei Yatchmeneff expressed their gratitude in a letter to Captain Dodge. “We feel had it not been for the prompt and efficient work of the Unalga, when everyone willingly and readily exposed himself to succor the sick, Unalaska’s population might have been reduced to a very small number if not entirely wiped out,” they wrote in July 1919. In the words of Captain Coffin: “Navy ships and nurses were sent to Unalaska after we yelled for them.” With the arrival of Navy vessels USSVicksburg and USS Marblehead arrival on 12 and 16 June, respectively, Captain Dodge was able to resupply the Unalga and set course for Bristol Bay. With its departure on 17 June, the Unalga’s relief of Unalaska officially concluded. While the Unalga’s performance at Unalaska drew universal acclaim, the cutter and Marblehead were criticized for arriving in the Bristol Bay region too late to make a difference. As the disease had mostly run its course, the Unalga’s crew worked with the Marblehead and onboard Navy personnel to provide medical care and aftermath cleanup in the community. When the pandemic finally released the territory from its grip, as many as 3,000 Alaskans had died, most of them natives, with irreparable loss to indigenous communities and cultures. In its 1920 Annual Report, the Coast Guard concluded the section “The Influenza at Unalaska and Dutch Harbor” with these words: “Occasion sometimes arise . . . in which the officers and crews are called upon to face situations of desperate human need which put their resourcefulness and energy, and even their courage, to the severest test.” Cutter Unalga and the men who sailed aboard it made history as part of the lore of Alaska and the long blue line.

Source:

Edited By Mary Kauffman, SitNews

Source of News:

|

||||